So this Mermé family is a new twist to this that I've not heard of before. It would be nice to learn more about the source of this information.Jean Dodal is attested as Master card-maker in Lyon between 1701 and 1715. On a graphic level, his tarot and that of Avignon editor Jean Payen are curiously similar. It is easy to conclude that these two decks were engraved in the same workshop. Dodal commissioned Jacques Mermé, engraver in Chambéry, to carve the woodblocks for the tarot he planned to edit. Mermé's son Claude, born in 1689, was hired to execute a tarot for Jean Payen in 1713, when he was 24 years old, and engraved another in 1745 for Jean-Pierre Payen. Jacques taught the rudiments of engraving to his son, but died in 1709 when Claude was barely 18 years old and had only just acquired the technical basis of his trade. Jacques Mermé includes many meaningful details, while Claude Mermé appears to take a perverse pleasure in including none. The inner sense of these images seems to escape him. The 'packaging' of Cluade's work for the Payens is correct, but the wine is ordinary and its effects mediocre.

It is important to distinguish between engravers and cartiers, or card-makers. In the beginning of the 18th century, card-makers became editors as we think of them today: image-merchants and paper salesmen. From 1701, for reasons of fiscal control, card-makers were forbidden to engrave their woodblocks themselves. In order to establish a revised tax regime most advantageous to the administration, the constabulary had the old woodblocks throughout France planed down or destroyed by fire in a series of wide-ranging raids... so card-makers were required make new plates conforming to new criteria. Dodal therefore called upon Jacques Mermé, specialized engraver and skilled Compagnon, to accomplish this task. The Dodal tarot can thus be dated with a high degree of certainty to 1701. It is Mermé the engraver who was responsible for the transmission of the wisdom borne by the tarot, and it is his mark as master (a chrisme, or stylized 4) he inscribed on IIII - L'Empereur.

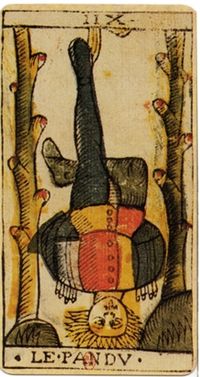

I've always questioned the relationship between the Payens and the Dodal. The decks are obviously related in some way, and I suppose a father and son engraver would make as much sense as anything. What surprises me in this is that I've come to consider the Dodal as a pretty "sloppy" copy of some earlier deck. It has some very strange attributes, such as the crossbeam on the Hanged Man missing, and the way that many of the titles seem to be cut into the picture. I assume that the deck shows a transition from a deck without titles to one that does.

The Dodal is made for export, as it clearly states on several cards. Export to where, I wonder?

And what of the alternate spelling of Dodal as marked on the cards... Dodali... is that French?

Additionally, the Dodal has the "I.P." on the Moon card that Jean-Michel brought to attention, and those initials are missing from the Payen decks. It does make sense to me that they might indicate J(I)ean Payen.

So I've never been quite able to figure it out. On one hand the Dodal seems different than the Payens in that there is evidence of a greater struggle with the title and number areas that doesn't show up in the Payen decks. On the other, the Dodal seems to have been made for export, and it has the I.P. initials on it.

So maybe thinking more about the Payens will help??

Another issue that Jean-Claude's booklet brought to mind is that the Payen family were an already established card making family that had moved from Marseille to Avignon in the 1680s. The whole "destruction of the moulds" scenerio really does need to be considered. This was raised by Ross several years ago, and includes a very good biography of the Payen family, I'm going to quote some of his posts from AT:

and later this:I have never read of the edict to destroy all the old moulds - I assume it is in d'Allemagne vol. II.

Two points only to clarify -

1. Avignon did not become part of France until 1791; until then, it was a Papal dominion. According to Chobaut, who studied the Avignon cardmakers most deeply ("Les Maîtres-Cartiers d'Avignon du XVe Siècle à la Révolution" 1955) No Parisian or Royal Edict concerning cards was promulgated there until 1756 (no legislation concerning cardmakers whatsoever in fact) when the King forced the Pope to allow the same tariffs on cards from Avignon as in France. Avignon was effectively dominating the market with much cheaper cards, to the detriment of Marseilles.

Therefore the Payen family, who were cardmakers in Avignon from 1686 until after the Revolution (the first Payen had been a card-maker in Marseille until 1686), could easily have preserved an *unbroken* tradition, and Payen's 1713 deck from Avignon therefore does not represent a recreation after the destruction of 1701. In Avignon, there was no destruction.

2. Dodal's deck could be dated anywhere from 1701 to 1715. There is no date on the pack. 1701-1715 are simply the dates when Dodal was active in Lyon. Therefore, Payen's could be earlier than Dodal's, strictly technically speaking.

And if Dodal had to recarve his plates, then Payen's is certainly to be preferred.

So if the Payens were making tarots since before 1686, and were making them in Avignon from 1686 onwards, and if they were free from any supposed requirement to destroy their moulds, why on earth would they hire an engraver to make their moulds for them? In comparison, Dodali seems rather a "fly by night" sort of character who was making cards for export for all of 15 years, and the Payens were a huge family of card makers stretching across centuries.Our Payen spent his whole life in Avignon, since he was three years old.

As far as "established himself in Avignon in 1710", Kaplan is actually misleading (not intentionally I am sure). What he should have said is that Payen "established himself *independently of his father*, in Avignon, in 1710."

Kaplan lists Chobaut in his bibliography, but since there is no asterisk it's hard to say if he's read it. Chobaut is authoritative because his research is constructed on primary documents. He actually studied the archives, the birth, death and marriage records, the records of the transactions, inventories, contracts, etc.

Note that "maître-cartier" - "master cardmaker" - is not a description of the quality of his work, it is a technical term meaning the "master" has established himself, he is no longer an "apprentice" working under someone else.

Chobaut on Jean-Pierre's father -

"Jean Payen (or "Payan" before 1700), born around 1654, son of François and Catherine Bourelly, established before 1686 as a merchant-cartier at Marseille; at Aix-en-Provence in 1679 he married Thérèse Geoffroy, daughter of Jacques; two of his brothers-in-law, Blaise Geoffroy and Jean Dreveton, husband of Marguerite Geoffroy, were master cardmakers at Aix-en-Provence.

"I know nothing of the reasons which made Jean Payen decide to establish himself in the Papal City [Avignon] in 1686. Doubtless, since the death of Guillaume Garet [the last noted master cardmaker in Avignon before Payen, died 1685] there had been no master cardmaker in Avignon, and Payen hoped to have less competition and be better protected from the French regulations than at Marseille or at Aix-en-Provence."

.....

"Jean Payen, followed by his sons, was extremely successful; he had many apprentices (...) Jean Payen was the first of 10 master-cardmakers of this family who worked in Avignon for the entire 18th century."

[snip details of addresses and apprentices - he became very rich - in 1697, he bought a paper-mill which his family owned until 1774. He died in 1731, appointing his eldest son Jean as heir. Chobaut also provides a genealogical chart].

Jean had four sons -

1) aforementioned Jean - 1680-1758; cartier in Avignon;

2) Jean-Pierre (our Jean-Pierre Payen) - 1683-1757; cartier in Avignon;

3) Pierre-François - 1687-1748; cartier first at Arles, then Avignon;

4) Armentaire - 1690 - ?; cartier at Arles.

The first son's story is interesting for us, since he became master-cardmaker as his father's heir, while he appointed his son the director of the papermill owned by the family. It was a virtual monopoly of Payens in Avignon.

Chobaut on Jean-Pierre Payen (ours) -

"Jean-Pierre Payen, baptised at Marseille the 29 June 1683, died at Avignon 27 September 1757, son of Jean, established at Avignon in 1686.

"Emancipated by his father at the time of his marriage, 2 June 1710, Jean-Pierre Payen established himself merchant-cartier and stationer on the 5 June, at rue Rouge or the Orfèvres, parish of Notre-Dame la Principale. On the 8th of July 1712, he bought a house and boutique, rue de l'Argenterie or Bancasse, parish Saint-Agricol, and there installed his industry and business.

"He appears to have had good rapport with his confreres in Montpellier: he had as apprentice in 1724, Nicolas Surville, and in 1730, Antoine Bacquier, both originally from this town; in 1735, his daughter Marie married Fulcran Bouscarel, merchant-cartier and stationer of Montpellier, son of Bernard, of the same profession.

"His eldest son, Jean-Pierre (1723-1793) would be a silk-merchant, then merchant-stationer and binder. The workshop and boutique of playing cards on the rue Bancasse went to the younger son, Joseph-Agricol."

Thus you can see that Kaplan's date 1710 is misleading; this is the year that Jean-Pierre Payen was emancipated by his father, and established himself as master-cartier in Avignon, *independently* of the other Payens. Kaplan makes it appear that 1710 was the year Jean-Pierre first came to Avignon from Marseilles; in fact, since three years of age he was in Avignon. 1710 is just the year he started his own business.

Hmmmmm.

Thoughts???