THE BELFIORE MUSES

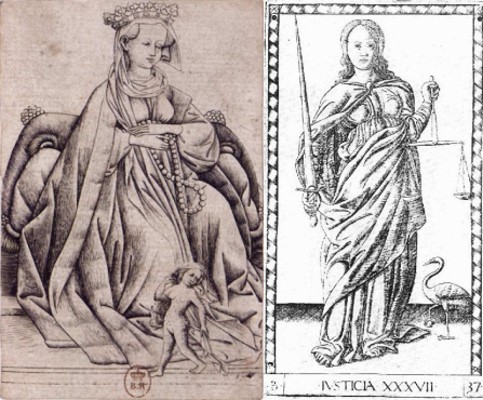

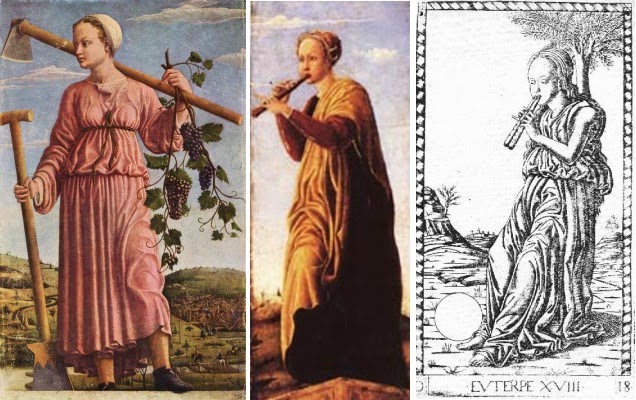

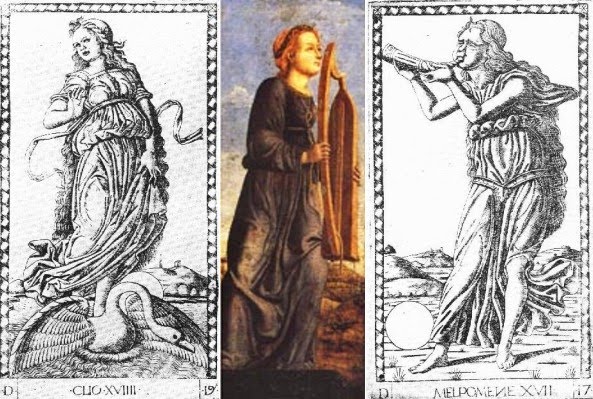

The first question I will address is this: in the style of what artist are the designs? To focus this question, here are two paintings done c. 1450 in Ferrara, along with the E series engraving of the "Mantegna's" Euterpe, one of the series of nine Muses. It would appear that the top half of one painting and the bottom half of the other combine to make one "Mantegna" Euterpe.

Art historians today agree, on good evidence, that the left-hand painting, now identified as the Muse Polyhymnia, was done for Leonello d'Este's studiola in his new Belfiore Palace, c. 1450. The other, Euterpe, is not much mentioned, but when it is (Gombosi, De Romanis), it is usually located at the same place. The palace and studiola were destroyed in one of the disastrous earthquakes, probably that of 1593, but likely eight of the paintings are still extant, in various museums, with various histories, and in various styles. (A convenient website to see seven of them, lacking only the one on the left above, and with a good summary, is Allesandra De Romanis's http://www.italica.rai.it/rinascimento/ ... lfiore.htm; I get from a post of Marco's on another thread.) In several cases, as x-ray studies have confirmed, paintings in one style were painted over, partly or wholly, and redone in a different style. The repainting is in the style of Cosmé Tura, and so by him and perhaps an assistant in the late 1450's, probably at the request of Borso d'Este, who succeeded Leonello as Marquis of Ferrara.

Four of the Muse paintings received only minor retouching. One, a Thalia, was done by Michele Pannonio, signed by him, and in a different style than any of the others; it does not concern us here. The others are the two above and one more in the same style, shown below. These three are the only ones that have their Muses standing rather than sitting. For both reasons, some historians (Baxandall, Eorsi, Boskovits, all cited on p. 169 of Campbell 1997) have theorized that they were done for a different series of Muses. However the wood on the left-hand painting above is from the same log as three other Belfiore Muses, and it has the same type of white undercoating, done before the modifications (Dunkerton, pp. 108, 109, 114)

The paintings loosely follow a program for them written by Guarino da Verona, Leonello's old tutor (Campbell 1997, p. 31, with the Latin original on p. 169). The Malatesta Chapel in Rimini followed his program more precisely. A quotation from the program actually appears on one of the other Belfiore Muse paintings. In Guarino's program, Euterpe was Muse of the pipes, and Polyhymnia, Muse of crop cultivation. The Euterpe appears to have been had part of its left side removed, as it is narrower than most of the others, although exactly the same length. Probably the same is true of the third one, identified as Melpomene, having the same dimensions.

What happened to the three after the Belfiore? According to 19th-early 20th century art historian Adolfo Venturi (p. 29), the two narrow ones served as side-panels in a Bologna church, as "angel-musicians," in Venturi's phrase, and then resided in the collection of Marquis Nerio Malvezzi of that city. They are both now in the Fine Arts Museum of Budapest. The Polyhymnia has been in Berlin since at least the 19th century.

THE ARTIST

So who painted these three? The antiquarian merchant and traveler Ciriaco da Ancona, who visited Belfiore on July 13, 1449, said that of the 9 paintings commissioned, 2 were completed, Clio and Melpomene; he names the artist as Angelo Parrasio. Here is his description of Clio:

This painting, although its description reminds me of a certain Vermeer (http://www.essentialvermeer.com/catalog ... nting.html), seems to have been lost. The "Mantegna's" Clio (at left, below) has something of the same mood, but with different accoutrements.The former, conspicuous for her dress embroidered in purple and gold, and for her blue chlamys, holds in her right hand a trumpet, in her left an open book, and with a certain modest hilarity in her expressive face, and something of a glance of her eyes, seems to urge men on to glory (Venturi p. 28f).

And here is Ciriaco's description of the Melpomene:

. He also mentions flowers at Melpomene's feet, painted so realistically that they deceived the bees (he is repeating a standard phrase, probably deriving from a classical source such as Philostratus). The Budapest Melpomene painting (center above) seems to have the same robe and harp.Her shoulders covered by a purple robe, she lightly touches the strings of her harp, turns her rapt gaze towards Olympus, and with modest and grave enthusiasm tunes her songs to the harmony of her chords.

Oddly, Venturi did not identify this description of a Muse with the painting at all, but simply called it an "angel musician." Perhaps he considered it too great a departure from Ciriaco's description, because of the improbability of flowers, and because she does not appear to touch the strings. But these are fine points; Ciriaco was a merchant, a promoter of goods, albeit one who had been to Egypt and knew his antiquities. To her right above, I put the "Mantegna" Melpomene. Obviously we do not have a match. The engravings are the product of a different environment, either with a different patron or one who changed his mind. But the style is similar. I will elaborate further on this point later.

The painter, whom Ciriaco called Angelo Parrasio, is also known as Angelo Maccagnino; he came to Ferrara from Siena in 1447, and Leonello put him in charge of the Muses project. Georg Gombosi, writing in 1933, attributed the Euterpe and the Melpemone to him. More recently Jill Dunkerton (2002, p. 114) attributed the Polyhymnia to him as well. But most scholars today disagree: none of the three is in Angelo's style. Dying in 1456, he was already old in 1450, and painted in an older style, visible e.g. in the upper body of the Erato, while the others reflect a new style, like that of Piero della Francesco. Campbell attributes the Polyhymnia to "an anonymous artist influenced by Piero della Francesca (in Ferrara around 1450)" (1997, p. 33). In the caption to the painting he says "Ferrarese, c. 1450" (p. 35). He does not discuss the others, but De Romanis, in her web essay on the Muse paintings already cited, attributes all three to "anonymous Ferrarese" ("anonimo artista ferrarese" and "ugualmente di anonimo ferrarese"). Nicoletta Guidibaldi, in Prospettive di Iconografia Muisicale (in Google Books)uses the same words.

Adolpho Venturi claimed that the painter of all three was one Galasso Galassi (p. 30), also called Galasso di Matteo Piva (p. 24), whom he also held, because of stylistic similarity, was the originator of the "Mantegna" designs. Venturi's opinion was reaffirmed in 1954 by Gnudi, and earlier by Longhi according to Gnudi, in a critical notice excerpted by Trionfi (in the section "Artists active in the Studiola," http://trionfi.com/0/m/16/).

Gombosi, in a 1933 Burlington Magazine article (at http://trionfi.com/0/m/16/) took issue with Venturi. He attributed the Polyhymnia to Galasso but the other two to Angelo, despite the lack of similarity in overall composition and mood to the other Angelo Muses, the ones altered by Tura. (At http://www.italica.rai.it/rinascimento/ ... lfiore.htm, compare Euterpe and Melpemone to Erato, Terpsichore, and Urania.) Gombosi based his attribution to Angelo on similarities to the other Angelo Muses in the depiction of folds in fabric, and on his identification of the landscape as Umbrian. However x-ray analysis since has revealed that the folds were put there later in the repainting (Dunkerton p. 116f); as for the landscape, it seems to me rather generic, easily learned from others' example. Gombosi noted the similarity in style of the Euterpe and Melpemone to the "Mantegna," to this extent following Venturi, and identified the cards as "Ferrarese (or Bolognese, but hardly Venetian)."

Galasso's name appears in one contemporary document, showing payment to Cosmé Tura and Galasso for appraising the value of some pennants done for the d'Este court in June 1451 (Venturi p. 29, Tyson p. 35). Tura was the artist in charge of painting over, in his style, all or part of some of the original paintings, all seated Muses: the unfinished Calliope completely, and three others, Erato, Urania, and Terpsichore partially (Dunkerton, pp. 108, 109, 114). So he and Galasso were in 1450 likely both students of Angelo, with similar ways of painting folds in fabric. But the three standing Muses are not in Tura's style. It is theoretically possible that he painted some of the originals in an early style and then painted over them later in a different style. But there is no documentation of Tura paintings suggesting that style.

Galasso's name next turns up in Vasari (Vol. 2, 1st edition only), who says that he was trained in Ferrara and then moved to Bologna at the invitation of "some Dominican monks" (p. 126), where he died at about age 50. According to Vasari's 1871 English translator, he lived 1438-1488. Venturi says he died in 1470 and that he worked for Bessarion, the papal legate in Bologna 1450-1455. Vasari's translator mentions another account of his life in a nineteenth century Italian source, which I have not consulted.

I have found only one recent art historian mentioning Galasso. Drogin, writing in 2002 of Bologna during the time of the Bentivoglio, says, "Piero della Francesca perhaps visited around 1450, followed by his student Galasso, to whom a 1455 Funeral of the Virgin is attributed (San Michele in Monte, destroyed 1831" (p. 80). Drogin does not give a reference.

I have been focusing on just one of the 50 images in the "Mantegna." But all are in a similar style, if not in the same hand. (Lambert, p. 145, suggests a workshop, an "atelier." Lambert is conservator in the Departement des Estampes et de la Photographie at the Bibliotheque Nationale, and her book is a catalogue of that library’s holdings.) The Muses, Virtues, and Liberal Arts are especially similar, mostly standing figures in robes. Before the "Mantegna" images this style was not a common one: I have seen nothing quite like them, apart from the three standing Muses of Belfiore. It is not unthinkable that Galasso took drawings of his three Muses with him to Bologna and with the help of humanists there, perhaps Bessarion himself, redid them and added more. One possible such humanist is a name that Trionfi mentions in their section, "Mantegna Tarocchi Engravers," for his interest in printers: Niccolo Perrati, Poet Laureate of Bologna in 1452 (the time of Frederick III's marriage journey), sometime secretary to Bessarion.

In this new environment, with new designs, it is the style that continues, not the programmatic details. Admittedly, no professional art historian today makes Venturi's leap to Galasso and Bologna. Instead, they usually say "anonymous Ferrarese," meaning "anonymous painter from Ferrara," as opposed to "painter in Ferrara," thus curiously not ruling out the possibility. Galasso was always a Ferrarese.

THE ENGRAVINGS: EVIDENCE FROM THE 1460'S

I turn now to the engravings. Most painters did not have engraving skills. Engraving started in Germany in the 1430’s, per Wikipedia, but both Ferrara and Bologna had active engraving and printing communities in the 1450's and later, including, at least in Bologna, German shops. Lambert (p. 146) classifies the "Mantegna" as "burin proche de la maniere fine Florentine," which I translate as "burin close to the fine Florentine manner." "Burin" in English means the engraving tool; perhaps in French it means "engraving" as well. Indeed, the "Mantegna" engravings are technically similar to Florentine ones of the 1460's reproduced by Lambert. Others that she attributes to Ferrara and elsewhere she calls simply "burin," except for Florentine ones, which she calls "burin en maniere fine." (Looking at the reproductions, I can't see any difference among them.) At that time, the 1450's and 1460's, Florence was closely allied politically with Bologna, Bologna's leading citizen having grown up in Tuscany and Florence; but Ferrara was considered an enemy. Numerous Florentine craftsmen came to Bologna to build and decorate the palaces of the rich, a trend in which the leading family set a strong example (Ady, p. 150ff).

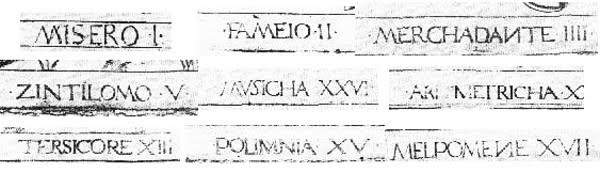

We do know that the next appearance of something similar to the "Mantegna's" imagery was in Bologna, in a 1467 miniature, of an Emperor and a Pope (Lambert p. 145 etc.). The miniature is posted by Trionfi at http://trionfi.com/i/mantegna-tarocchi/index2.php. I post the relevant section below, underneath three “Mantegna” cards. Trionfi observes, in their comments below the photo, that besides the Emperor and Pope is also a figure similar to the "Mantegna" Servant, "Il Fameio." I assume they mean the person at the far left of the Pope. So above the miniature, I put all three cards for comparison. The figure of the Servant is possibly repeated to the Pope's right; but the face and costume resembles more the Merchant. I also see the Chevalier behind and to the left of the Emperor, possibly repeated on his right. And there is a bearded version of the "Mantegna" King kneeling before the Emperor. I post these three below the miniature, for ease in making visual comparisons.

Possibly the four minor characters are stock figures of a generic nature. Lambert does not list them. The Emperor in the miniature is indisputably a close match with the "Mantegna" Emperor (and also the figure in its “Jupiter”: see http://trionfi.com/mantegna/e/e-mantegn ... chi/46.jpg). With the Pope there are some similarities, such as the tiara and the keys, but also some differences. His posture is different. The robe is more elaborate, filled with abstract designs. The face is different, too. So is the miniaturist's version a a more complex version of the card, but with a rounder face, or is the cardmaker's a simplification of the miniature, with a thinner face?

The posture can be explained by reference to the other side of the illustration, with the Emperor: the two figures are meant to complement each other. This explanation, while accounting for the difference, does not answer our question of which came first. The face and robe, I think, demand a more complex explanation, but one that may yield more interesting results.

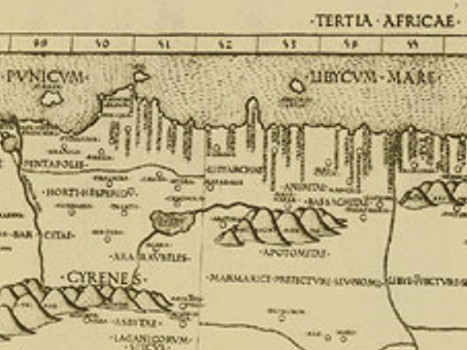

We must first look at the "Mantegna" Pope card in the context of 15th century Popes. One of Trionfi's arguments for the engravings' late date, c. 1475, is a resemblance that they perceive between the "Mantegna" Pope and Sixtus IV, who became Pope in 1471 (see their "Pope Sixtus IV - Pictures" page). Admittedly, the man on the card is not similar to his predecessor, Paul II, who reigned while relatively young and portly. But I am arguing that the cards were designed in the 1450's, in the form of drawings; so we should also compare the card to the Popes then. There is also the element of the keys in the "Mantegna" Pope's hand. Nicholas V, the Pope who appointed Bessarion papal legate and let the Bolognese largely run their own affairs (Ady, p. 37), had just such keys as his personal device, frequently added in the corner of his portrait. Here is an example:

And if not Nicholas V, there were two after him in the 1450's; even without the device, keys were associated with Popes. I cannot see how the Pope card looks more like Sixtus IV than any of these. Below are Nicholas V (1447-1455) and his keys, Callistus II (1455-1458), Pius II (1458-1464), and Sixtus IV (1471-1484) (http://catholicsites.org/popes/renaissance.html), with the "Mantegna" in the middle.

Actually, to me the closest match is with Callistus II and Pius II. I am not sure what is in the corner of Nicholas's portrait; perhaps it contains the keys bunched together as on the card.

Now the strange result--well, not so strange--is that the Pope in the miniature does not look like any of the above, but rather like Paul II, the Pope from 1464 to 1471, whose likeness we see on the right below:

So we can date the miniature to the period 1464-1467, as indeed it is. But the card, based on this evidence, is likely either before or after that period. I of course think it was before. But at least we have an explanation of why the face is different.

As for the robe, it may be that Paul II wore such things. The portrait posted on Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pope_Paul_II) shows a golden robe with intricate designs. He was 47 when elected Pope and so may have lacked the austerity that often comes with age. He had been a merchant before changing careers when his uncle was elected Pope (in the end advancing from a lower “Condition of Life” to the highest.) And the late 1460's was a time for magnificence: Florence's Medici, Milan's Sforza, Bologna's Bentivoglio, Ferrara's Este, etc. Such a robe also gave the miniaturist a place to show off his skill. Moreover, the patterns themselves have an interesting characteristic, at the top and bottom of the double key that the Pope is holding in his right hand: the patterns merge with the key edges, so that someone might not recognize the key at first. It is a kind of visual double entendre, another way in which the miniaturist shows off his skill. For the pun and its reference to be appreciated, however, people would likely have to have been familiar with the card; Nicholas V and other popes were not shown actually holding the keys in the manner depicted.

So tentatively we can say that the manuscript came after the card, or at least the image on the card. This conclusion is further substantiated by another manuscript, this one dated 28 November 1468. The four “Mantegna” virtue cards were inserted as miniatures in Foir di Virtu, a book on the virtues kept in the Saint-Gallen Library and completed 28 Nov. 1468. Trionfi has an image with the four pages superimposed on a "Mantegna" Prudence (http://trionfi.com/i/mantegna-tarocchi/index.php). Trionfi has posted a description of the miniatures from a German text, but I can't locate it at present. Here is Lambert's description (p. 145)

She observes that...quatre tarots inserés dans son texte: La Tempérance, La Prudence, La Force et La Justice."

My translation: "The writing overflows the margins of the prints, which proves that they were in place prior to the composition of the manuscript." I do not know where this book was produced, and cannot even tell what language it is in; but it clearly shows that at least these four cards were extant by 1468."L'écriture déborde sur les marges des estampes, ce qui prouve que celles-ci étaient en place antérieurement à la composition du manuscrit"

Where there are four Virtues, there are probably three more. Where there are 6 Conditions of Life, there are probably more. The PMB tarot already had its Fool resembling the “Mantegna” Misero and its Bagatto resembling the Artisano. By 1468 we already have close to the 20 cards of the “Mantegna’s” 50. And the ‘Pope” card refers us to pre-1464 and even the time of Nicholas V, 1447-1455. In addition, the Belfiore 3 standing Muses account for the design of most of the Muses, Liberal Arts, and Virtues, as standing male or female figures in robes. All that is left are the Spheres, stock representations of the planetary gods.

THE LAZARELLI HYPOTHESIS

From the early 1470's, the most interesting and complete dated appearance of the images is in the manuscript of a long poem by Ludovico Lazarelli. Trionfi suggests that Lazarelli is the one who created most of the "Mantegna" cards because he included in his manuscript 23 of the designs, the first datable appearance of so many, plus 4 more not part of the "Mantegna." They postulate that after this manuscript, Lazarelli completed the set c. 1474-75 and had the engravings made by a German printer in Rome c. 1475. (Their argument is in various places: the main material is at http://trionfi.com/0/m/16/, in the sections "Hind's error," "Hind's final suggestion," and "Lazarelli Hypothesis," with more at http://trionfi.com/i/mantegna-tarocchi/index2.php, repeated at http://trionfi.com/mantegna/.)

Several objections occur to me. There is of course the problem of the earlier manuscripts with, first, 2-6 images like the cards, and later 4 images of actual cards. Where there are 6 (or 10) there are probably more. There are also the Belfiore Euterpe and Polyhymnia, which seem to have inspired the "Mantegna" Euterpe and probably other of the Muses. We are to suppose that Lazarelli somehow got copies of some or all of these, and in the same style invented 27 more for his manuscript. He does not, strictly speaking, have to have had the 1467 and 1468 manuscripts, because there is no trace of either the Conditions of Life or the Virtues in his manuscript, according to Trionfi's reports. But there are the Muses and many other Muse-like figures among the Virtues and Liberal Arts; so he does have to have had images of at least one of the Belfiore standing Muses, or something like them, to get their style.

After the manuscript, according to Trionfi, Lazarelli finished the set of 50. It seems to me that if so, then he must have now acquired copies of the 4 St. Gallen and at least the Pope and Emperor from the Bologna manuscript, to use as models for those cards, as well as something very close to the Belfiore Euterpe, since the designs for the Muses and Liberal Arts are so similar. All this from a person whose other documented work is in the medium of words, none of which is about any of the cards' subjects except that which appears together with the 27 miniatures. The result, one I find hard to believe, is a work that will be printed in numerous editions, imitated by famous and not so famous artists for many years, preserved carefully for posterity (in 13 complete sets of the "E" series alone, according to Lambert), and admired to this day.

There may be other difficulties with the Lazarelli hypothesis, but without better reproductions of his images they must remain unresolved. There are, among other things, questions of technique and style: consistency between illuminations and cards, between the 23 "Mantegna" subjects and 4 additional ones in the manuscript (of non-planetary gods, whose imagery might well have been Lazarelli's invention), and between all of these and the 7 in the previous manuscripts. One cannot tell much from the available black and white reproductions of Lazarelli's illuminations, 9 in Kaplan (Vol 1, p. 27) and 6 more posted by Trionfi.

The alternative story, from whatever source (an "insecure note," according to Trionfi), is that Lazarelli picked up the designs as prints in Venice, around 1468 or 1469. As Trionfi notes, it is not clear whether on this account they were woodcuts or engravings, colored or black and white. So they could have been engravings, like the "Mantegna" we know, perhaps hand-painted, as the Sola-Busca were a little later. Or the color was added by Lazarelli. The dates make sense. According to Campbell (2004), Lazarelli's manuscript was finished by 1471. That dating is secure, according to both Campbell and Lambert, and acknowledged also by Trionfi. The reason is that on one of the two copies there are "traces of a canceled dedication to Borso d'Este," as Campbell puts it (2004, p. 127). (His reference is to an article by Lamberto Donati, "Le fonti iconografiche did alcuni manoscitti urbiniti della Biblioteca Vaticana," in La Bibliofile 1958, 60-1, 48-129.) Borso died in August of 1471; normally the dedication would be added last, in case of just such eventualities. The location also makes sense: the writing at the bottoms of Lazarelli's images, as well as of the cards, is in the Venetian dialect, suggesting prints for the Venetian or at least Northeast Italian market.

THE ART HISTORIANS

On the engravings, so far I have been focusing on Trionfi's theory that they were made c. 1475, mostly from designs by Lazarelli c. 1470 but also drawing on a few designs made slightly earlier than his involvement. Art historians have a different perspective. Campbell concludes that the "Mantegna" was "devised by a Ferrarese artist and circulating by the 1460's" (2004, p. 127). Tyson agrees (p. 57), suggesting a candidate for the designer, Gherardo da Vicenza, the triumph-card maker, because his dates are right, because documents show that he designed other things for the Estensi, such as silverware, and because there are possible affinities between the cards and anonymous sections of the Schifanoia frescoes. To me that is not much of an argument for Gherardo in particular.

Lambert, following Hind, simply suggests "vers 1465" (p. 145: "around 1465") in Ferrara. Her argument is the 1467, 1468, and 1471 manuscripts, and the alleged stylistic similarity to the frescoes of the Schifanoia generally, which she attributes to del Cossa. It would take me too long for me to compare the cards to the Schifanoia here. Historians writing in Italian and English say that many artists were involved; some, it seems to me, may even not have been resident in Ferrara, because Borso wanted the job done quickly.

Different historians have found resemblances to different sections (although none to the one section del Cossa claimed to have done). Gnudi argues, in the excerpt posted by Trionfi (“Artists active in the studiola”), for a resemblance to the December "Triumph of Vesta." Gnudi, Trionfi says, was in charge of the restoration. I can find no pictures of this scene on the Web, and in books accessible to me only a drawing done a century or so ago (in Roettgen, Italian Frescoes: the Early Renaissance, p. 414) It is of a quite deteriorated fresco, one that looks to me rather generic Northern Italian.

Tyson (p. 59f) sees resemblances to some very different figures in the June, July, August, and September sections, both men and women, in the middle and lower upper parts. To me these all look either too inventive and energetic for the cards or again generic. On the other hand, the cards are close enough to these images that they could have been used by the painters in preparation for their work, since the Schifanoia was done 1469-1471, presumably after the cards. I invite the reader to inspect the frescoes on the Web. I will expand on these points if desired.

One reason that Campbell gives the 1460's rather than earlier, is his theory (2004, p. 126f) that several literary and artistic productions of that time, including the "Mantegna" and the Lazarelli poem, were reacting to the seductive, morally ambiguous nature of the Belfiore Muses, as they were in the late 1450's; they wished to present the Muses in a more elevated way. Whatever the merits of this argument, it applies only to the Tura repaintings, and not to the three unaltered ones. And it seems to me that that the tenor of the times in Ferrara, as shown by Tura's and del Cossa's intensity and the bold, warm, earthy imagery shown by much of the Schifanoia, counts against any such airy but conventional revisioning as the "Mantegna" at that time.

THE “MANTEGNA”: CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER SPECULATIONS

I agree that the engravings were probably done in the 1460's; I would say perhaps before 1465. And I think they are based on designs from the 1450's, closer to the beginning or middle of the decade than the end, and more likely in Bologna than Ferrara. For Bologna, I offer (a) Galasso's move there, as the most likely candidate for the "anonymous Ferrarese" whose style is closest to the cards; (b) the marked divergence of the "Mantegna" from Borso's (as opposed to Leonello's) Belfiore Muses and most of the Schifanoia; (c) the presence there of the 1467 miniature, (d) the keys of the Pope card as Nicholas V's device, and possibly (e) the resemblance in engraving technique to Florentine engravings of the time and (f) the later presence there of the Belfiore Euterpe and Melpemone. Moreover (g), Bologna, with its internecine feuds, suffered from too much passion and intensity; the elevated but conventional mood of the cards, in contrast to the best of Ferrarese art, would have been welcome there. For the designs, in favor of the 1450's we have the 3 Belfiore Muses, Galasso's move, reference to Nicholas V in the Pope card, and facial features in that card similar to the Popes of the 1450's. For the engravings, in favor of pre-1467 we have the same manuscripts that the art historians cite. In favor of pre-1465 we have the resemblance to pre-1464 Popes and lack of resemblance to Paul II. I have no idea who the engraver was.

Why were the cards made? They are visual representations of the "great chain of being," from the lowest representative of humanity to God himself. They are humanist propaganda for the adoption of the Greco-Roman tradition by artists, writers, and the educated public, and they are Christian propaganda for their subservience to Christianity. They are a defense of the power of the established social order, the Virtues, the Liberal Arts, the Muses, and the Greco-Roman myths to elevate humanity step by step to an appreciation of the divine. They might also have been an instructional card game with five suits. But if so, the instruction about many of the Muses and a few of the Liberal Arts is not very good, as many are not very differentiated from one another; the classical sources provided them with much more distinctive visual attributes.

Perhaps the cards were made in connection with specific celebrations, and in something of a hurry (which would explain the repetitive nature of the Muses). If occasions in Bologna are desired, the wedding of Sante Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza in 1454 comes to mind for the hand-made version, and that of Giovanni II Bentivoglio and Ginevra Sforza in 1464 (Ady p. 139) for the engravings. Ginevra seems to have had a special interest in the printing industry (Ady p. 162).

If Bessarion was a force behind the project--if not of the original designs, then at least of the engravings--they could have been made almost anywhere, although still from designs made in Bologna. Bessarion was based in Rome but attended the Congress of Mantua in 1459, visiting Bologna both before and after. The old story (in Seznec, p. 138f, and Brockhaus, posted by Trionfi) about Pius II, Cusa and Bessarion devising the game at Mantua could have a sliver of truth: not a game, and not Cusa or Pius, just Bessarion. Bessarion, who later, according to Wikipedia, founded the Petrarch library, was very much present at the Congress, and so were delegates from everywhere, any of whom could have participated in the project of making the engravings.

Even Mantegna, by then resident in Mantua, could have been involved. Vasari, to be sure, spoke of Mantegna's engraved "triumphs," but one must be careful not to take him out of context. As Ross and probably others have already pointed out, Vasari was undoubtedly referring to Mantegna's engravings of his fresco cycle, "The Triumphs of Caesar," to which Vasari previously devoted an entire long paragraph using the same words of praise. (See http://www.efn.org/~acd/vite/VasariMantegna.html.)

But according to Joscelyn Godwin (Pagan Dream of the Renaissance. p. 50, in Google Books), Giannino Giovannoni argued as late as 1981, hopefully on better grounds than some, that Mantegna designed the cards at the Congress. According to him, Mantegna designed Virtues and Muses for his tomb very similar to the cards, which were then put there by his pupils. That last is a claim that I have so far had no opportunity to verify. If one compares Mantegna's engravings in general with those of the "Mantegna," it is clear that the two artists' styles are totally different, as revealed e.g. in how the two depict the folds in fabrics: Mantegna's are complex, even busy, while those on the cards are simple, repetitive, and calm. Yet if he did identify at the end of his life with some of the designs sufficiently to want them on his tomb, perhaps he had a hand in their production or distribution, which in fact was so wide, resulting in imitation so extensive (I have not told half), that it was easy to believe that a famous artist must have done them.

For tarot researchers, the main practical consequence of my conclusions thus far, about the relation of the "Mantegna" designs to Bologna in the 1450s-60s, is that we should not rule out their influence on the various emerging designs of the tarot. As printed hierarchical exemplars of the various classical deities and Renaissance walks of life, the two sequences could easily have interacted at an early date, the tarot influencing the "Mantegna" and vice versa.

REFERENCES NOT DETAILED IN POST OR LINKS

Ady, Cecilia, 1937. The Bentivoglios of Bologna.

Campbell, Stephen J., 1997. Cosmé Tura of Ferrara.

Campbell, Stephen J., 2004. The Cabinet of Eros: Renaissance Mythological Painting and the Studiola of Isabella d'Este. In Google Books.

Drogin, David, 2002. "Bologna's Bentivoglio Family and its Artists: Overview of a Quattrocento Court in the Making, in Artists at Court: Image-Making and Identity, 1300-1550, 2002, ed. Stephen Campbell, pp. 72-90.

Dunkerton, Jill, 2002. "Cosmé Tura's Painting technique," in Cosmé Ture: Painting and Design in Renaissance Ferrara, ed. Alan Chong, pp. 107-152.

Giovannoni, Giannino, 1981. Mantova e i tarocchi del Mantegna.

Lambert, Gisele, 1999. Les Premieres Gravures Italiennes: Quattrocento--Debut du Cinquecento.

Seznec, Jean, trans. 1953. Survival of the Pagan Gods: The Mythological tradition and its Place in Renaissance Humanism and Art, trans. Sessions.

Syson, Luke, 2002. "Tura and the 'Minor Arts': The School of Ferrara," in Cosme Turé: Painting and Design in Renaissance Ferrara, ed. Alan Chong, pp. 31-70.

Vasari, Giorgio, 1871 translation of 1550 original. Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Vol. 2, translator Johnson, in Google Books.

Venturi, Adolfo, 1931. North Italian painting of the Quattrocento: Emilia.