Nathaniel wrote: 06 May 2022, 09:34

But, of course, we both need to try to stop ourselves being swayed by our personal preferences and focus on the evidence instead. You have begun to present evidence for a later dating of the Rothschild cards. To balance that, I can point to the evidence for an earlier dating, in the 1420s:

As summarized by Ada Labriola in "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle" (p. 117), all the Italian art historians who have examined the Rothschild cards have preferred a date in the 1420s for them: Christina Fiorini, Emanuele Zappasodi, and of course Ada herself. This is a lot to argue against, I think.

The authority and expertise of art historians is a lot to argue against by someone not trained in that discipline, I agree. But I am trained in documentary history, with particular expertise in Tarot history, and I think this side of the story has something to say. So I'm still going to argue against it.

One general point is one you yourself make, which is the conservatism of playing cards, because players need and expect consistency, clarity and simplicity, in cards where the only way to identify them is visually. So, like a cartoonist who draws the same figures for years and decades unchanged, the playing card artists made them rapidly and formulaically. Like the cartoon figures, it is very hard to judge the date of composition from such a figure alone. These subjects are unlike carefully executed pieces. Unless some aspect or detail gives a clear indication of the date of a sketch, it could be almost any time in a definable period of an artist's style.

Thus Tarot history would say that the Rothschild cards are what they appear to be,

carte da trionfi. And, because of that, they must date no earlier than a couple of years before 1440. Because they are rapidly executed paintings, coloured sketches, following a formula or model, conservative, they are not as susceptible to precise dating as careful or complex works, especially ones done with a collaborator.

This is why I was happy that Ada Labriola allowed herself to imagine a date a decade later than the standard dating methods for Giovanni dal Ponte suggested. I think it was courageous, and I'll continue to stand up for her dating.

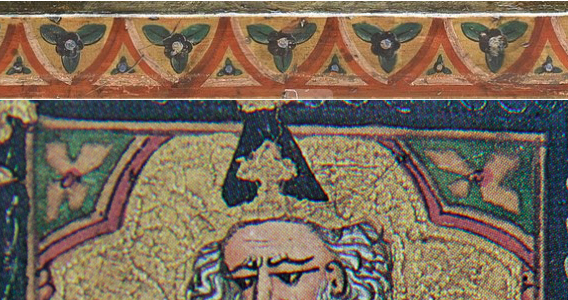

Upthread I gave some examples of border designs from Giovanni's later work which compares well with the borders and gothic tracery on the cards. They are unique, not appearing anywhere else in his work, at least as I know it from Sbaraglio's catalogue. So, since everybody is looking for comparisions in Giovanni's known works, I think these late incidental and decorative details are relevant to bringing the date later.

Here is another response I began writing, arguing similarly.

Until we identified Florence as the home of much of the earliest Trionfi card production, art history was of limited value for Tarot history. Look at how long Ferrara held on as other centre, besides Milan. From Klein in 1967, through the 70s up to Dummett, the 80s with Giuliana Algeri, all through the 1990s and up to the point where Florence broke through, definitively in 2012. The art history expertise alone did not help Klein or Algeri identify them as Florentine, which seems so clear now. It took plain documentary history to wrest the cards from Ferrara.

Now that we are securely in Florence, the floodgates have opened. We are in the vicinity of named artists and ateliers. Bellosi was the first to identify Giovanni dal Ponte's contribution, but he knew nothing of playing card history. He had no idea what a revolution his identification meant, and it was premature in any case because no documentation from Florence was yet known, to put his ideas in context.

This has all changed now, in the last 16 years. But the lesson remains: playing cards, even the luxury ones, are not standard art historical subjects. The Lombard cards like Issy-Warsaw and Bembos' are more like fine miniature paintings than the Florentine productions, and Longhi identified Bembo's hand in them nearly a century ago. This is probably due to the mass market nature of the Florentine cards, in contrast to the princely court tastes. Florentine figures are like cartoons compared to the Lombardy cards. The traditional art historical method of tracing changes of style over a long period in an artist's career, based on carefully executed paintings done over months or years, is somewhat unfitted to the rapid sketches comprising the cards. Art historians know this, of course, and look, in Giovanni dal Ponte's case, to the sketches and most rapidly executed pieces to find analogues. Here, as in the case of Giovanni's "Two Youths," the clothing and comparison with contemporary artists painting similar figures persuaded Bellosi to comfortably date it to 1425-1430. He compared Giovanni's figures to a fresco by Masolino from 1425. But Masolino made another one in 1435, where the figures are very similar. If we didn't know the date from documentation or Masolino's biography, we wouldn't be able to date the frescoes from the figures alone (Bellosi actually also argues for the clothing being the style of 1425-1430; the sketch is lost now, maybe it will turn up one day).

Right, two figures from Masolino, fresco in the Baptistery of Castiglione Olona, 1435

Luciano Bellosi, the first to identify Giovanni as the painter, characterised the cards as “cursive” (modi corsivi) and “almost impressionistic” (quasi impressionistiche). They are essentially sketches (“abbozzi” - Bellosi). I think that an artist's sketching style doesn't change as much over his career as his highly finished works, often done with a collaborator. Especially when you are focusing on a period as short as ten years when the artist is already mature. So, I would argue, a sketch of 1427 could well be indistinguishable from a sketch of 1437, as long as an internal clue like a very distinctive clothing style doesn't date it precisely. And, on playing cards, much of it is fantasy, and conservative.

The only reason we care so much is because it impacts the dating of the invention of Tarot, or the nature of Imperatori cards. Otherwise “1425-1430” versus “1430-1435” would be laughable to argue about.

So, how can we really distinguish the former from the latter? Or, the six-year period before 1430 (inclusive), from the six-year period (actually eight inclusive, of course) after 1430?

Bellosi gives us a start.