Just to record here some French trionfi mss. with illustrated triumphs not yet mentioned in this thread.

Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, MS 1125; Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, MS 6480; Paris, BnF, MS fr. 12423.

Not sure how complete they are. Some images from them are on the internet.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

142Thanks Mike. I should look through the Inventari dei manoscritti delle biblioteche d'Italia myself at some point, there could be something interesting there. There are several other, similar inventories that could yield something interesting too. The Friuli and Cortona mss were known to me, but not the Tranne one, and all I knew of the Cortona one is what is said here:

https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscrip ... laccademia

The description there isn't quite as interesting as in the Inventari.

Where did you find the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève manuscript? I don't think I'd seen that one anywhere, although maybe I just wasn't interested because the text is a French translation and its illuminations have been removed. Apparently a copy of one of the illuminations exists, at least; but unfortunately it's Love, which tends to be the least interesting. This one is no exception:

https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/iiif/13315/ca ... 55174/view

https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscrip ... laccademia

The description there isn't quite as interesting as in the Inventari.

Where did you find the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève manuscript? I don't think I'd seen that one anywhere, although maybe I just wasn't interested because the text is a French translation and its illuminations have been removed. Apparently a copy of one of the illuminations exists, at least; but unfortunately it's Love, which tends to be the least interesting. This one is no exception:

https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/iiif/13315/ca ... 55174/view

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

143I found the St. Geneviève and the others at https://brill.com/edcollchap-oa/book/97 ... f_FN210055, note 55. It has "damaged" after the citation, so perhaps missing some illustrations.

I don't know that going through the Inventori that are online will do you much good. The other ones, yes, if you have access to them.

I have been reading more of Trapp, in his Studies of Petrarch and his influence, 2003. His essay "Petrarch's Triumph of Death in Tapestries" is of interest not so much for the tapestries as for his remarks on the manuscripts that use the theme of the three fates. That is one of the themes that connects the French Robertet ms with the Master of the Vitae Imperatorum ms., so I was interested in what he might have to say about the France-Italy connection.

Trapp mentions at least one, possibly two more in Italy. Not only that, Robertet's verses inscribed on the Trionfi illustrations go back to at least 1480 (other sources say c. 1476) and the quatrains in Latin, he says, to 1450 (although I can't find confirmation of the latter). In the Triumph of Death, they both mention the Fates. Moreover, Robertet visited Italy sometime before 1464.

He begins by contrasting the Florentine versions (first paragraph) with Petrarch's text, then getting to the ones of our interest:

Well, it is possible. Or a snake around a stick; but that makes no sense in this context. I resume quoting Trapp, same paragraph, immediately following:

Well, it is possible. Or a snake around a stick; but that makes no sense in this context. I resume quoting Trapp, same paragraph, immediately following:

I uploaded all the images of this ms. (Death at the end) at viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=25903&hilit=3943#p25903. It is perhaps worth noting that for Trapp this ms. is not just ca. 1445 or 1445-1450, but perhaps even 1430s. Cohen, as pointed out already in this thread has it later, 1460s.

It was nice that Trapp shows how the illustration relates to the poem. I had not noticed the hair plucked from Laura's head (https://petrarch.petersadlon.com/read_t ... e=III-I.en):

I continue: (Added later: The whole page at lower resolution is at the end of this post, where "0006" should have been.)

(Added later: The whole page at lower resolution is at the end of this post, where "0006" should have been.)

Trapp then turns to France. He discusses several mss. of around 1503 or so, noting their differences from the Italian Triumphs of Death. Among them are three with the Fates.

Here it should be said that there were several Jean Robertets. Besides the poet who died c. 1503, there was the grandson, probably the "Ja. Robertet" who signed as copyist of some of Jean Senior's works, first mentioned in 1510 and died in 1530 (p. 8 of 1962 Ph.D. dissertation by Catherine Margaret Douglas, at https://www.proquest.com/openview/965da ... 366&diss=y. He is also called Jean-Jacques Robertet. In between was the elder Jean's son, François, who died sometime between 1524 and 1530, and another son, Jean-Jacques (and others). François may have been the artist, as well as the scribe for at least some of 24461's verses, according to an article on Jstor ("François Robertet: French sixteenth-century civil servant, poet, and artist," by C. A. Mayer and D. Bentley-Cranch). However, the verses they quote from François's own poem on the Triumph of Death does not mention the three fates, which seems odd if he was the artist that drew them for his father's verses.

Trapp goes on:

There is also one more French series of triumphs in France from this same period, in stained glass. Trapp's reproduction is rather unclear; fortunately, it is on the web, at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File ... _76754.jpg. From left to right, the triumphs are said to be top row Fame, Eternity, Time, lower row Love, Chastity, Death. I would note in passing that Chastity has a notched shield, as in Vat.Barb.3943 and also Bib.Nat.Fr. 549, whose Death Trapp had just discussed (and of course the Visconti di Modrone tarot card).

Trapp continues:

Curiously, the huitain just cited for Death combines Death with Fame in the sense of "eternal glory." Robertet expresses something similar in his huitaine for Fame (which I get from Zsuppan's 1966 article)

It would be good to get the rest of Robertet's French huitaines and Latin verses. They might have clues as to their origin. They are on the illustrations, but my transcription of that script is not up to the task, and the Oeuvres does not seem to be online.

Added next day: also, since Trapp says that BNCF B. R. 103's Death is non-standard, I will try harder to get it; and it would be good to find an online source for the Berlin Staatliche Museen Preussische Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, MS. 78. D. 11 Trionfi illustrations other than the two we have (Death and Fame). And as long as I'm wishing, the two Canzoniere books, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130, f. 10v and 115r, and Madrid, Biblioteca nacional, MS. Vit. 22-3, f. 1v and 6r.

Also, there is more about the connection between the Robertet illustrations and the Canzoniere books in another essay in Trapp's book, "The Iconography of Petrarch in the Age of Humanism." First he describes the Bodmeriana illustration (Cologny-Geneve, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130 f. 10v):

Finally, here are the relevant pages of Trapp's essay, pp. 174-181 and 23-24:

I don't know that going through the Inventori that are online will do you much good. The other ones, yes, if you have access to them.

I have been reading more of Trapp, in his Studies of Petrarch and his influence, 2003. His essay "Petrarch's Triumph of Death in Tapestries" is of interest not so much for the tapestries as for his remarks on the manuscripts that use the theme of the three fates. That is one of the themes that connects the French Robertet ms with the Master of the Vitae Imperatorum ms., so I was interested in what he might have to say about the France-Italy connection.

Trapp mentions at least one, possibly two more in Italy. Not only that, Robertet's verses inscribed on the Trionfi illustrations go back to at least 1480 (other sources say c. 1476) and the quatrains in Latin, he says, to 1450 (although I can't find confirmation of the latter). In the Triumph of Death, they both mention the Fates. Moreover, Robertet visited Italy sometime before 1464.

He begins by contrasting the Florentine versions (first paragraph) with Petrarch's text, then getting to the ones of our interest:

I interrupt Trapp to show what he is talking about. A low-resolution color version of the whole page is at https://www.bsb-muenchen.de/en/collecti ... up-c3429-3. Going into the Munich site itself (same URL, but without the group number), it is possible to get a higher resolution image, in black and white only.174 The iconography of the Triumph of Death, like that of the Trionfi in general, was established in Italy and, more specifically, in Florence, during the second quarter of the fifteenth century. It was transmitted first in manuscript illuminations, followed by Florentine engravings and by the woodcuts of the editions printed in Venice in 1488 and the 1490s.8 As in their treatment of others of the Trionfi, these illustrators of the Triumph of Death make rather free with Petrarch's poem. They do not, for example, in general make a great point of the fact that the whole is the record of a dream vision. They illustrate a procession, which Petrarch does not describe. They most frequently make Death the conventional skeletal and/or masculine figure, where Petrarch describes a black-draped woman. Death's triumphal car is drawn by oxen or by buffaloes, not mentioned by Petrarch. Italian illustrators of the Triumph of Death lay little stress on the figure of Laura.

There are exceptions, naturally, to this last generalization. In Italian manuscripts, the Triumph of Death is sometimes shown in ways that accord better with Petrarch's description.9 Sometimes, too, the poet's vision in the second capitolo is illustrated. This recounts how, on the night following her death, he dreamed of how his dead beloved seated him and herself by a stream in order, at the capitolo's end, to impart the fatal sentence that he has more to endure: 'Tu starai in terra senza me gran tempo'.10

To consider exceptions in the present context we need to begin with the miniature which opens the Trionfi in the first illustrated manuscript of the poem. The codex is one of those in which the text of the Trionfi opens with the second capital of the Trionfo della morte, it is a product of northern

____________________

8. Trapp (n. 3 [misprint for n. 2?: Trapp is not mentioned in n. 3]), pp. 39-48, 53-56.

9. E.g. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, MS. Vit. 22-3, fol. 161' (?Rome, 1508), Trapp (n. 2), Pl. XXXIII; Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, MS. B. R. 103, fol. J[2] (a printed book with inserted miniatures, painted perhaps in the 1480s); Trapp (n. 2 ["The Iconography of Petrarch in the Age of Humanism," originally 1992-93, but now 1-117 of the present volume]), Pl. XLIV; L. Armstrong, 'The Master of the Rimini Ovid. A Miniaturist and Woodcut Designer in Renaissance Venice', Print Quarterly, X, 1993, pp. 353-9.

10. E. g. Giovanpietro Birago, in London, British Library, Add. MS. 38125, f. 58r; Trapp, PI. XXXIV.

PETRARCH'S TRIUMPH OF DEATH IN TAPESTRY 175

Italy, dated 1414 and probably illustrated by Stefano da Verona.11 Leaving aside the question of whether any of the six ladies seated in the chariot shown in the miniature represent the Fates, we may decide that the figure in the incomplete initial below is Clotho with her distaff confronting the

poet.

________________

11. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, MS. ital. 81, fol. 146r'; A. Sottili, I codici del Petrarca nella Germania occidentale, 2 Vols., Padua, 1971-8 (Censimento di codici petrarcheschi, IV, VII), no. 82; S. Samek Ludovici, I Trionfi illustrati nella miniatura da codici precedenti del sec. XIII al sec. XVI. Studio con note esp[icative, 2 Vols., Rome, 1978, I, pp. 116-7; II, PI. VII.

Here is the image:In a manuscript of some quarter-century later, there is no room for doubt. This is a Trionfi codex executed in Lombardy and illustrated by the Master of the Vitae Imperatorum, who was active in Milan during the 1430s and 1440s.12 No procession is depicted in the miniature at the head of this manuscript's Trionfo della Morte. In four unequal compartments it shows, to the left, the dead of all ages and conditions and, to the right, the aged and emaciated coming forward as if to embrace their death.13 A bow is held against Death's body by the left hand, while the right is extended over Laura's head, as if to pluck a hair from it.14 There is a refulgence behind Death's shoulder. In the lower centre compartment sit three female personages, who do not figure in Petrarch's text. They are the three Fates: Clotho with her distaff, Lachesis measuring out the thread of life, Atropos reaching to cut it with her shears.

__________________

12. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, MS. Barb. lat. 3943, fol. 170v; Samek Ludovici, I, pp. 118-9; II, PI. XIII; A. C. de la Mare, 'Script and Manuscripts in Milan under the Sforza', in Milano nell'età di Ludovico il Moro. Atti del Convegno internazionale, Milan, 1983, p. 399.

13. Trionfo della Morte, I, ll. 73-81.

14. Trionfo delta Morte, I, ll.113-4.

I uploaded all the images of this ms. (Death at the end) at viewtopic.php?f=11&t=906&p=25903&hilit=3943#p25903. It is perhaps worth noting that for Trapp this ms. is not just ca. 1445 or 1445-1450, but perhaps even 1430s. Cohen, as pointed out already in this thread has it later, 1460s.

It was nice that Trapp shows how the illustration relates to the poem. I had not noticed the hair plucked from Laura's head (https://petrarch.petersadlon.com/read_t ... e=III-I.en):

Petrarch mentions the pope and emperor, but for him they stand naked around Death, as opposed to being in full regalia but supine, as we see in the tarot cards and most Triumphs of Death.And then from her blond head the hand of Death

Plucked forth a single sacred golden strand; ...

Here, it seems to me, the illustration is different from Petrarch's description. The poor on the right side are not rulers bereft by Death of their riches, but poor people desiring death, due to their suffering in this life, as opposed to the other side that fears death. The people in rags are like those on the left side of the "Triumph of Death" fresco in Palermo (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Trium ... Palermo%29: but I take their 1440-45 dating and non-Italian artist with a grain of salt; it could just as well be a little later and by an artist of the Schifanoia, it seems to me, as argued by Julian Mitchell at https://studiesinconnoisseurship.tumblr ... h-of-death).Here now were they who were called fortunate,

Popes, emperors, and others who had ruled;

Now are they naked, poor, of all bereft.

I continue:

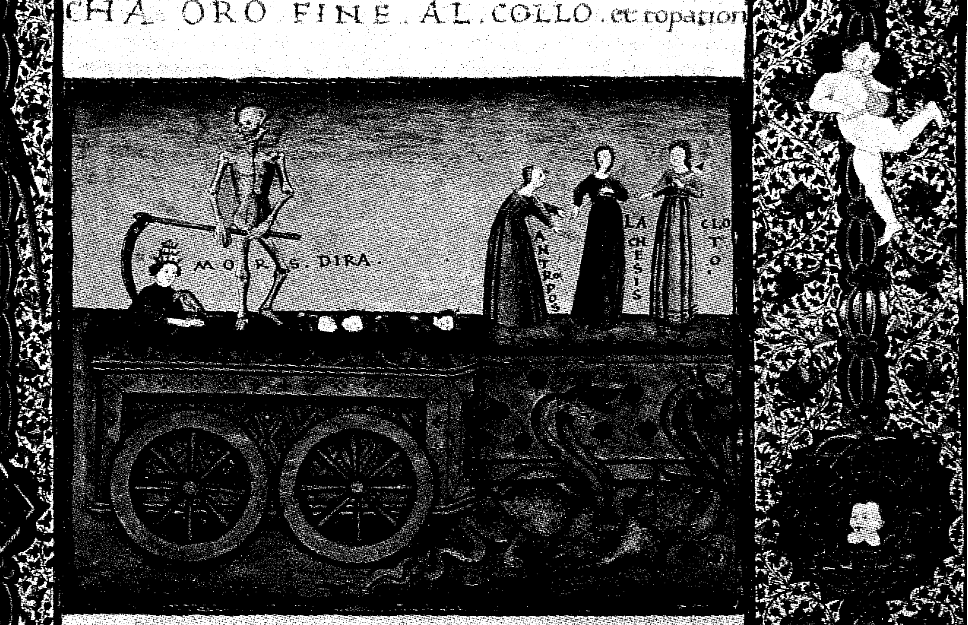

This is in the same manuscript which has the elephant-driven triumph with a Wheel of Fortune on the chariot as its Triumph of Time. I cannot find a copy of the ms.'s Triumph of Death on the internet, so here is Trapp's black and white reproduction (many of the details invisible in my scan!):Laura does not figure in the only other Italian illustration of Petrarch's Trionfo della Morte known to me in which the Fates are present. This is in a manuscript illuminated, probably in Naples, in the second half of the fifteenth century, by an artist with affinities to Niccolo Rubicano, who was active in that city 1451-88 (Fig. 1).15 A skeletal Death (MORS DIRA), is standing on the corpse of a beheaded king towards the rear of a gold chariot drawn by a pair of serpents and a pair of dragons. Other dead strew the

___________________

15. Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, MS. 78. D. 11, fol. 116r; Sottili, no. 217; ? Wescher, Beschreibendes Verzeichnis der Miniaturen-Handschriften und Einzelbaetter des Kupferstich-kabinetts der Staatlichen Museen Berlin, Leipzig, 1931, pp. 84-86.

176

car, while behind Death a Pope is shown at half-length, with a falcon on his wrist and half-encircled by the curving blade of Death's scythe. Above and behind, to the right of the miniature, are the Fates, labelled ANTROPOS (sic.), cutting the thread held by LACHESIS as it comes from the distaff of CLOTO (sic.).

Trapp then turns to France. He discusses several mss. of around 1503 or so, noting their differences from the Italian Triumphs of Death. Among them are three with the Fates.

It is again, as in Vat.Barb.3943, Laura and not popes and emperors lying supine, but the three Fates are above her. replacing skeletel Death. See https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Cate ... -death.jpg. After describing the illustration he adds:They are three, all belonging, seemingly, to the early sixteenth century, perhaps to about the same time as Louis XII's Trionfi manuscript [i.e. ca. 1502]. Some at least of their contents are either designs for or records of tapestries. Each contains a minimum of text, being rather a collection of pictures, with or without tituli. One is now in Chantilly, two others in Paris (Fig. 4).22 The two last mentioned are close copies one of the other. The copy in the Bibliotheque nationale de France is of finer artistic quality than the others and, like the Arsenal codex, possibly shows some acquaintance with illustrations of Petrarch's Canzoniere in manuscripts written in Italy by Bartolomeo Sanvito at the beginning of the sixteenth century and by Ludovico Arrighi in 1508.23

________________

22. Chantilly, Musée Condé, MS. 509; Paris, Bibliotheque de l'Arsenal, MS. 5066; Bibliotheque nationale de France, MS. fr. 24461; Pellegrin, pp. 192-3; 204-8; 257-9.

23. See Trapp, pls. XVII-XVIII [17 is 'Petrarch', Apollo and Daphne-Laura Transformed: Allegory of Poetry; Cologny-Geneve, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130, f. 10v; Padua, first decade of the sixteenth century. 18 is Giovanni Battista Cavalletto, 'Petrarch', Apollo and Daphne - Laura Transformed: Allegory of Poetry; Madrid, Biblioteca nacional,

MS. Vit. 22-3, f. 1v; Rome, 1508] and cf. fols. 115r and 6r respectively. For MS. fr. 24461, see P. Vandenbroeck, 'Dits illustres et emblemes moraux. Contribution a l'étude de l'iconographie profane et de la pensée sociale vers 1500', Jaarboek van het Kon. Museum voor Schoone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1988, pp. 23-96.

My attempt at translation (the translation of the Latin is a big guess).Accompanying the miniature are the Latin quatrain composed about the mid-fifteenth century, a Latin couplet and the French huitain by Jean Robertet(d'. c. 1503), dating from perhaps about 1480, all summarizing the content:

Celibis abscindunt neruos et fila sorores

Nec durat fragilli vita pudica solo;

Sanior hac longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse sed heu! tandem singula morte cadunt.

Mors vincit Pudicitiam.

Combien que lomme soit chaste et tout pudicque

Les seurs fatalles par leur loy auctentique

Tranchent les nerfz et filletz de la vie;

A ce la Mort tous les viuans conuie.

La chaste au fort plus sainement peult viure,

Qui ce treuve de grans vices deliure,

Mais en la fin il ny a roy ne pape,

Grant ne petit qui de ses las eschappe.

La Mort vaint Chasteté.

Tergemine gladio dum claudunt fata sorores

Ambo sunt nostra sub dicione poli.

24. Jean Robertet, Oeuvres, ed. critique par Margaret Zsuppan, Geneva 1970, pp. 181-2. The Chantilly manuscript has only the French huitain. Cf. Robertet's approximate contemporary Henri Baude, Dictz moraulx pour faire tapisserie, ed. A. Scoumanne, Geneva & Paris 1959, esp. p. 89; and for other French verse summaries, Pellegrin, p. 188. See also Guy Delmarcel, 'Text and Image. Some Notes on the Tituli of Flemish "Triumphs of Petrarch" Tapestries', Textile History, XX, 1989, pp. 321-9; and Jean Michel Massing, Erasmian Wit and proverbial Wisdom. An illustrated moral Compendium for Francois I, London, 1995, p.52.

All three mention the three Fates. If the first is 1450, that is quite early. But he gives no explanation for the dating. As for the 1480, the Oeuvres does not seem to be online. But a 1966 essay by a C.M. Zsuppan, "AN EARLY EXAMPLE OF THE RENAISSANCE THEMES OF IMMORTALITY AND DIVINE INSPIRATION: THE WORK OF JEAN ROBERTET" is in Jstor, and there we learn that his "Triomphes de Petrarque (с. 1476)" is "a very short and over-simplified adaptation of Petrarch's long and involved Trionfi."The sisters cut off the sinews and fibers of the celibates

Nor does the frail life of chastity last alone;

Healthier than this long health celebs [?]

But alas! at last each one falls to his death.

Death conquers Chastity.

As much as man is chaste and very modest

The fatal sisters by their authentic law

Cut through the sinews and fibers of life;

To this Death all lives are condemned.

The chaste to the strong can live more healthily,

[than one?] Who finds great delirious vices,

But in the end there is neither king nor pope,

Great or small who escapes them.

Death conquers Chastity.

Triple sword while the sisters close fate

Both are under our control.

Here it should be said that there were several Jean Robertets. Besides the poet who died c. 1503, there was the grandson, probably the "Ja. Robertet" who signed as copyist of some of Jean Senior's works, first mentioned in 1510 and died in 1530 (p. 8 of 1962 Ph.D. dissertation by Catherine Margaret Douglas, at https://www.proquest.com/openview/965da ... 366&diss=y. He is also called Jean-Jacques Robertet. In between was the elder Jean's son, François, who died sometime between 1524 and 1530, and another son, Jean-Jacques (and others). François may have been the artist, as well as the scribe for at least some of 24461's verses, according to an article on Jstor ("François Robertet: French sixteenth-century civil servant, poet, and artist," by C. A. Mayer and D. Bentley-Cranch). However, the verses they quote from François's own poem on the Triumph of Death does not mention the three fates, which seems odd if he was the artist that drew them for his father's verses.

Trapp goes on:

Again there is an article by Zsuppan (JEAN ROBERTET'S LIFE AND CAREER: A REASSESSMENT", 1969, in Jstor) that explains the "some time before 1464." It is a piece of correspondence in an exchange known as les Douze Dames de Rhetorique, Zsuppan says after quoting it (without translating): "Possibly it was as a student that Jean visited Italy; 6 certainly the visit, which must have taken place before 1464, the probable date of the correspondence mentioned above, was of major importance in Jean's formation, since his introduction of aspects of Italian culture to France constitutes the most interesting part of his work." Her footnote explains that his name cannot be found in any lists of French students in attendance at Italian universities in this period. He is mentioned in France in 1458 and then in Dec. 26, 1461, "when he had probably already been in Duke Jean II's service for some time." This is the Duke of Bourbon, whose court was in Moulins, central France, not far from the king's in Blois. The Duke was much involved in the Hundred Years' War against the English. Jean advanced to becoming a secretary to Louis XI.180

Were it not for their appearance in at least two Italian miniatures, one would be inclined - with Essling and Muntz - to regard the introduction of the Fates into the Triumph of Death as a French contribution to Petrarchan iconography, and the textual responsibility for it largely Robertet's. Even if we do not so regard it, there remains the difficulty of how Robertet might have seen the miniatures. It is true that he was in Italy some time before 1464.25 No provenance for any of the manuscripts I have mentioned is available for a period before the later sixteenth century.

_______________

25. Zsuppan, p. 9.

There is also one more French series of triumphs in France from this same period, in stained glass. Trapp's reproduction is rather unclear; fortunately, it is on the web, at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File ... _76754.jpg. From left to right, the triumphs are said to be top row Fame, Eternity, Time, lower row Love, Chastity, Death. I would note in passing that Chastity has a notched shield, as in Vat.Barb.3943 and also Bib.Nat.Fr. 549, whose Death Trapp had just discussed (and of course the Visconti di Modrone tarot card).

Trapp continues:

Trapp then goes on to discuss the tapestries, but I will stop here.The Fates had made an appearance in France, perhaps before these drawings were made, in the Triumph of Death which forms part of the remarkable stained-glass window with representations of all the Triumphs in the church of St-Pierre-es-Liens in Ervy-le-Chatel (Aube) (Fig. 5)16. This was the gift in 1502 of Jeanne Le Clerc, widow of Pierre Girardin, late bailli of Ervy. Death is half skeleton, half cadaver, wearing a crown, a shield on his right arm, standing before an arch on a sort of platform suspended on chains from the beak of a bird and the neck of a dragon. Along the edge of the platform is the legend Cloto. Atropos. Lachesis, below which again Love and Chastity are crushed. To the left, just above her name, sits a skeletal Clotho with her distaff. To the right, a little above, an equally skeletal Lachesis is perched, holding the thread which then passes into Death's left hand, for him to perform the function of Atropos on it. Death's right hand holds three darts and his skull is reflected in a mirror to his left. Scriptural quotations on banderoles drive home the message, which is repeated below in a huitain by an unknown author, perhaps in emulation of Robertet:

La mort commune et naturelle

Met tout en sa subgecti[on]

Mais cest aux bons gloire eternelle

Et aux maulvais [confusion;]

L'on ne peult avoir vision

De gloire sans ce pas pas[ser];

Vivons doncq sans abusion

Tout fauk morir et trepasser.

[Machine translation:

Common and natural death

Puts everything in its subjecti[on]

But it is to the good eternal glory

And to the bad [confusion;]

We cannot have vision [?]

Of glory without this step;

Let us therefore live without abuse

Everything must die and pass away.]

_____________________

16. Prache and N. Blondel, eds., Les vitraux de Champagne-Ardenne, Paris, 1992 (Corpus vitrearum Medii Aevi: France, IV), pp. 100-103; Essling-Mintz, pp. 201-6. For Jerome de Busleyden's now lost stained glass Trionfi in Mechelen, of probably a few years later, see above, p. 173; for other surviving sixteenth-century stained-glass Trionfi roundels see, e.g., Y. Vanden Bemden, 'Rondels representant les Triomphes de Petrarque', Revue Belge d'archiologie et d'histoire d'art, XLVI, 1977, pp. 5-22; and William Cole, A Catalogue of Netherlandish and North European Roundels in Britain, Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi: Great Britain, Summary Catalogue, I, London, 1993, Cat. nos. 416, 719, 1638, 2467.

Curiously, the huitain just cited for Death combines Death with Fame in the sense of "eternal glory." Robertet expresses something similar in his huitaine for Fame (which I get from Zsuppan's 1966 article)

Edited machine translation:La Mort mort tout, mais Clere Renommée

Sur Mort triumphe et la tient deprimée

Dessoubz ses piedz. Mais après ces effors

Fame suscite les haulx faictz des gens morts,

Qui par vertu ont meritée gloire,

Qu'après leur mort de leur fait soit memoire.

Inclite Fame n'eut jamais congnoissance

De Letheus, le grant lac d'oubliance.

Bonne Renommée vainc la Mort.

If Fame has no knowledge of oblivion, it must be immortal, for those whose great deeds are accompanied by virtue. I do not know if this is moral virtue or just valor, but it is similar in sentiment to the "triumph de virtute" illustration discussed a few posts back. Not only that, but it seems to be those responsible for preserving the memory of those "who by virtue have deserved glory" that gives them Fame and hence immortality. That seems to be a different treatment of Fame than Petrarch's in the Trionfi, although not contradicting it (and something I think he says elsewhere). Hence both the book (preserving the memory) and the sword (for the high deeds) in Fame's hands in Vat.Barb. 3943, which also precedes the first draft of the Triumph of Fame (although without a second one after it).Death kills all, but Clere [Clear? Bright?] Renown

On Death triumphs and keeps her depressed

Under his feet. But after these efforts

Fame arouses the high deeds of dead people,

Who by virtue have deserved glory,

May their death be remembered.

Iillustrious Fame had no knowledge

Of Letheus, the great lake of oblivion.

Good Fame conquers Death.

It would be good to get the rest of Robertet's French huitaines and Latin verses. They might have clues as to their origin. They are on the illustrations, but my transcription of that script is not up to the task, and the Oeuvres does not seem to be online.

Added next day: also, since Trapp says that BNCF B. R. 103's Death is non-standard, I will try harder to get it; and it would be good to find an online source for the Berlin Staatliche Museen Preussische Kulturbesitz, Kupferstichkabinett, MS. 78. D. 11 Trionfi illustrations other than the two we have (Death and Fame). And as long as I'm wishing, the two Canzoniere books, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130, f. 10v and 115r, and Madrid, Biblioteca nacional, MS. Vit. 22-3, f. 1v and 6r.

Also, there is more about the connection between the Robertet illustrations and the Canzoniere books in another essay in Trapp's book, "The Iconography of Petrarch in the Age of Humanism." First he describes the Bodmeriana illustration (Cologny-Geneve, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130 f. 10v):

Then he discusses the Madrid version, one in New York, and one that seems to borrow from them among the illustrated pages of Robertet.In a landscape part rocky, part amenable, Pegasus stamps his hoof on Helicon-Vaucluse to produce the spring of Hippocrene-Sorgue. In the background lies Avignon. Below, on one bank of the river, sits Apollo with his viol, facing a laureate Petrarch seated with book and pen on the other, beneath the green bay-tree into which Daphne-Laura has been partially transformed, her head and [start p. 25] shoulders remaining to show what she once was. In the tree's branches hovers Love, drawing his bow at the poet.108

___________________

108. Cologny-Geneve, Bibliotheca Bodmeriana, MS. 130, f. 10v; F. B. Adams, A Petrarch Manuscript in the Bodmeriana, MS. 130, f. 10v; F. B. Adams, A Petrarch Manuscript in the Bodmeriana, in: IX Internationaler Bibliophilen-Kongress,1975 in der Schweiz. Akten und Referate, Zurich, 1975, 1975, pp.71-85; M. Feo, Il pianto e l'amore, in: Uomo Naturanella nella letteratura e nell'arte italiana del Tre-Quattrocento, Firenze, 1991 (Quaderni dell'Accademia delle Arti del Disegno, 3), p. 38, Fig. 14.

It seems to me that if a drawing perhaps uses a motif in a ms. of 1508, it might have been done later than 1509. While BNF Fr. 24461 (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... /f279.item) is an amalgamation of several small booklets (according to the "About" blurb), on f. 138v - a different booklet than f. 115, but with similar lettering - is a sketch of a portrait medal of Francis I with the words "FRANCISCUS * PRIMUS * F * R * INVICTISSIMUS", which would seem to celebrate a military victory, which he only attained in 1515, at Marignano (pointed out by Mayer and Bentley-Cranch, pp. 219-20). Jean's son Florimond Robertet, whom Francis made Treasurer of the Realm upon his accession in that year, was with him. It is worth noting also that the drawing on f. 115 has Florimond's coat of arms (p. 217).There is a version (Fig. 18) of the same composition on the purple first folio of a fine manuscript written and dated 1508 by Lodovico Arrighi.109 A variant of the image occurs in other earlier and later manuscripts, in which

Petrarch sits alone in a landscape under a bay-tree.110 A rifacimento, with Love asleep and Hercules standing rather than Apollo and Petrarch, appears in a French manuscript containing Jean Robertet, Les six triomphes de

Petrarque, made about 1509.111

_____________

109. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional, MS Vit. 22-3, F. 1v; Villar, Espana, no. 79.

110. E.g. New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS. 427, f. 67.

111. Paris, Bibliotheque Nationale, MS. Fr. 24461, f. 115; Pellegrin, France, pp. 257-259 (III, 475-477).

Finally, here are the relevant pages of Trapp's essay, pp. 174-181 and 23-24:

Last edited by mikeh on 18 Nov 2023, 08:41, edited 4 times in total.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

144Trapp simply means that the 24461 drawing draws on some Italian image similar to the one in the manuscript of 1508, not that it is a direct copy from that particular manuscript. As he says, there are Italian manuscripts both earlier and later which have similar images. You can see from the illustrations Trapp provides in that "Iconography" essay that the Italian images he cites are not close enough to the 24461 image for the latter to have been copied directly from them.mikeh wrote: 17 Oct 2023, 14:24 It seems to me that if a drawing perhaps uses a motif in a ms. of 1508, it might have been done later than 1509.

It's basically just more evidence that the Robertet work drew on numerous Italian images (there are plenty of other examples in it, as I have said before in this thread).

It seems fairly clear (from various bits of evidence discussed by Ziegler in Recueil Robertet: Handzeichnung in Frankreich um 1500, among others) that the Triumphs section of 24461—the first section—was completed sometime around 1500, well before 1509. And the images in that section must have been copied quite closely from Italian images that were a lot older than that, as I have already said. In regard to that:

Trapp's date of "at least 1480" seems to be based on that date of c. 1476, which comes from Zsuppán. But she had no firm basis for that date. In my view, Robertet probably did not compose the French verses until much later, sometime around 1490 or so, because there is no indication at all of their existence until the 1490s, and then suddenly we start to see a great deal of evidence of their existence, largely in the form of tapestries that either contain them or appear to be related to ones that did.Trapp mentions at least one, possibly two more in Italy. Not only that, Robertet's verses inscribed on the Trionfi illustrations go back to at least 1480 (other sources say c. 1476) and the quatrains in Latin, he says, to 1450 (although I can't find confirmation of the latter).

But it is the Latin quatrains that are really of interest to us. You've misrepresented Trapp slightly here: he did not say 1450, but rather "about the mid-fifteenth century", as can be seen in the section you quoted in your post.

I'm not yet sure where he got this from—presumably one of the sources in his footnote 24, but neither Zsuppán nor Delmarcel; the others I have not yet seen—but it appears to be correct.

A version of these quatrains, with slightly different wording, can be found in ms. alfa.U.7.24 in the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria in Modena. Another page in this manuscript in Modena (f. 105r) is dated 1447. I have not yet ascertained if anyone has given an expert opinion about whether the Trionfi section of the manuscript is the same age as the folio with that date on it. There are certainly two poems in the manuscript (ff. 93r–93v) that were later, from 1450 and 1463 respectively, but the dated page is in the section containing Petrarch's poems, so that makes it look like the Trionfi part is from about 1447 too.

There is another French manuscript of the Trionfi (in two volumes, ms. 5065 in Arsenal and ms. Fr. 12424 in BnF) that also contains the Latin quatrains, but in a wording that is closer to the Modena manuscript than Robertet's wording is. This is a strong indication that the Italian manuscript from which Robertet took the Latin verses, or a copy of it, was brought to France and was seen by others apart from Robertet. There is therefore no need to assume that Robertet saw these verses when he himself was in Italy.

If you read the Latin poems, it becomes clear that they were composed as an explanation for the accompanying images. They appear to be a kind of exegesis, seeking to make sense of the pictures. This impression arises for a number of reasons.

First, they put a lot of stress on the fact that the figures are standing on their vanquished victims, as if the author felt that this was something unusual that needed justification (and of course, we know that it would indeed have been unusual in the context of Trionfi illustrations in Italy).

In order to give sense to the drawings, the verses also interpret a few of their features in unorthodox ways, giving them meanings that were quite different from the conventional meanings usually given to them in this context. The Chastity verses are the best example of this. As a result, it looks like the person who created the drawings may well have viewed them quite differently from the way the poet chooses to view them, suggesting that the poems were written sometime after the drawings were created.

However, it is nevertheless also possible that the poems were composed at the same time as the images, with the poems provided as explanatory captions for the them, rather than an exegesis by someone else later.

What does not seem possible, on the other hand, is that the poems were composed first, without the images, and then the images were added later, even though this is what has usually been assumed by those who have examined ms. 24461. The images must have been composed either at the same date as the verses, or at an earlier date. They could not have been a later addition to the verses, because the entire purpose of the verses is to explain the images.

The verses in ms alfa.U.7.24 are not accompanied by the images, so the verses and therefore also the images must date from even earlier than this manuscript. Not only that, it looks as though these images were themselves based on some other, earlier images which presented the allegorical figures in a more orthodox arrangement, i.e., without the vanquished under their feet. The best evidence of this is Eternity, who looks as though she ought to have an image of the world below those semicircular arches.

Those original images would therefore be likely to date from the early 1440s at the latest, placing them right at the beginning of the era of Trionfi illustration. Note also that the close correspondence of the Latin verses to the images in ms. 24461 inclines one to conclude that Robertet and his artist copied the original images quite faithfully, with minimal change. So what we see on the six pages of this French manuscript from c. 1500 appear to be faithful copies of Italian Trionfi illustrations from the early 1440s or before.

But of course, we still need to try to verify that 1447 date for that manuscript.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

145Nathaniel wrote,

For more detail, click on the link:

This is to be sure not proof that BnF Fr. 42461's image is later than ca. 1508. There may be an earlier Italian source for both of the two. For post-1515, there is only the sketch of the medallion for Francis I - again, only suggesting post-1515.

For more detail, click on the link:

This is to be sure not proof that BnF Fr. 42461's image is later than ca. 1508. There may be an earlier Italian source for both of the two. For post-1515, there is only the sketch of the medallion for Francis I - again, only suggesting post-1515.

We also have to consider the coat of arms on f. 115v's tree limb, that of Florimond Robertet, Jean's son, next to Hercules. At what point in his life could he be compared to Hercules? Well, he went with Charles VIII to Italy in 1494, but did not do anything Herculean that I can find, except maybe keeping track of money and goods. He went again in 1499 and the years following. The war against Julius II and the Venetians, culminating in the battle of Agnadello in 1509, seems to figure prominently for both the Duke of Bourbon and Florimond. BnF Fr. 42461 has a page allegedly showing the Duke on horseback at Agnadello: "F. 141: Représentation du connétable Charles III de Bourbon à la bataille d'Agnadel en 1509"), says the "About" blurb on the BnF page. As for Florimond, I see a French website commenting, based on a recent book by a French historian (https://www.historia.fr/actu/florimond- ... 80%99heure):

Traveling in high position with the kings from 1494 on, he would have been on the lookout for Trionfi mss., based on his father's interest if nothing else, aided by the father's fame for bringing Petrarch and Boccaccio to the attention of French-speaking courts. If Petrarch illustrations didn't become popular until the 1490s in France, I would attribute that more to booty brought back from the French incursions than to Jean Robertet's verses.

Nathaniel wrote

Nathaniel wrote,

However, if there is a codex with quatrains in 1447 all talking about victors standing on or driving over their squashed victims, and if a copy of it got to France, that might explain better this major difference between the Italian illustrations - except a few Triumphs of Death - and some of the French tapestries and mss., of which the one with Robertet verses and his son's coat of arms is just one. And its verses might presuppose a ms. with images. But I'd have to see all the various verses.

This applies to the rest of what you say, too. Also, please tell us what relevant evidence Ziegler has, as this is a book I probably won't even be able to get via interlibrary loan, as it's very rare in U.S. libraries.

Just so anyone who might read our exchange might be able to figure out what we are talking about, here are Trapp's two relevant "source" illustrations for an illustration in 42461. (I apologize for not giving them earlier), followed by, on the left below them, the image he sees as similar in 42461, and the second one the "Triumph of Death" illustration in the same ms. It is the cliff, the Pegasus, and the castle on the upper right, I think. If BnF 42461 f. 115v is similar to the upper two, then f. 4v is also similar enough to be related, because of the cliff. The similarity seems enough for Trapp to date the 42461. To be sure, there are borrowings from many Italian images in the codex, many of them earlier than these. But these two are close enough to define the time-period of the codex. That is what Trapp is saying.mikeh wrote: ↑17 Oct 2023, 14:24Trapp simply means that the BnF Fr. 24461 drawing draws on some Italian image similar to the one in the manuscript of 1508, not that it is a direct copy from that particular manuscript. As he says, there are Italian manuscripts both earlier and later which have similar images. You can see from the illustrations Trapp provides in that "Iconography" essay that the Italian images he cites are not close enough to the 24461 image for the latter to have been copied directly from them.

It seems to me that if a drawing perhaps uses a motif in a ms. of 1508, it might have been done later than 1509.

It's basically just more evidence that the Robertet work drew on numerous Italian images (there are plenty of other examples in it, as I have said before in this thread).

We also have to consider the coat of arms on f. 115v's tree limb, that of Florimond Robertet, Jean's son, next to Hercules. At what point in his life could he be compared to Hercules? Well, he went with Charles VIII to Italy in 1494, but did not do anything Herculean that I can find, except maybe keeping track of money and goods. He went again in 1499 and the years following. The war against Julius II and the Venetians, culminating in the battle of Agnadello in 1509, seems to figure prominently for both the Duke of Bourbon and Florimond. BnF Fr. 42461 has a page allegedly showing the Duke on horseback at Agnadello: "F. 141: Représentation du connétable Charles III de Bourbon à la bataille d'Agnadel en 1509"), says the "About" blurb on the BnF page. As for Florimond, I see a French website commenting, based on a recent book by a French historian (https://www.historia.fr/actu/florimond- ... 80%99heure):

I think the writer is referring to how the French harassed half of the Venetian forces, so that it slowed down compared to the rest; the French then annihilated that half. Over half the other half then deserted overnight. This is in 1509. After that, he is credited with engineering the marriage of Claude of Brittany with the future Francis I, making Brittany part of France. 1515 of course had its own military victory, with Florimond participating.Et que dire de ce moment du règne de Louis XII où la France voit poindre la menace d’une grande coalition, ourdie par le Pape Jules II et qui fédère entre autres l’Empire germanique et les royaumes italiens. Une nouvelle fois, Robertet est à la manœuvre, parvenant à désolidariser les Vénitiens de l’offensive contre la France ; un gain qui s’avère décisif pour empêcher le royaume d’être sur la pente descendante.

And what can we say about this moment in the reign of Louis XII when France saw the threat of a great coalition emerging, hatched by Pope Julius II and which brought together, among others, the Germanic Empire and the Italian kingdoms. Once again, Robertet is maneuvering, managing to break up the Venetians in the offensive against France; a gain which proves decisive in preventing the kingdom from being on a downward slope.

Traveling in high position with the kings from 1494 on, he would have been on the lookout for Trionfi mss., based on his father's interest if nothing else, aided by the father's fame for bringing Petrarch and Boccaccio to the attention of French-speaking courts. If Petrarch illustrations didn't become popular until the 1490s in France, I would attribute that more to booty brought back from the French incursions than to Jean Robertet's verses.

Nathaniel wrote

I can't read them unless I can see them. When I get to the url in question (https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscrip ... versitaria), all I see is "summary of the Triumphi in Latin elegiac couplets," without saying what they are, and nothing about quatrains. Even if I could see the actual pages, I would not be able to read what was written, because of the script. Nor can I read what is on the pp. of the two French mss. Nor do I know what Zsuppan proposed as Jean Robertet's 1476 huitaines and Latin quatrains, except for the Triumph of Death and the Triumph of Fame's huitain. It would help if you could report the relevant 6 quatrains in the Modena ms., the 6 you see in BnF Fr. 12414 and Arsenal 5065, the 6 in 42461, the 6 in 5066 (if different); and the 6 of Robertet, plus his huitains, other than the ones I have quoted (photos of Zsuppan's pages will do). Then I and others could try to evaluate what you are saying and perhaps accept it.A version of these quatrains, with slightly different wording, can be found in ms. alfa.U.7.24 in the Biblioteca Estense Universitaria in Modena. Another page in this manuscript in Modena (f. 105r) is dated 1447. I have not yet ascertained if anyone has given an expert opinion about whether the Trionfi section of the manuscript is the same age as the folio with that date on it. There are certainly two poems in the manuscript (ff. 93r–93v) that were later, from 1450 and 1463 respectively, but the dated page is in the section containing Petrarch's poems, so that makes it look like the Trionfi part is from about 1447 too.

There is another French manuscript of the Trionfi (in two volumes, ms. 5065 in Arsenal and ms. Fr. 12424 in BnF) that also contains the Latin quatrains, but in a wording that is closer to the Modena manuscript than Robertet's wording is. This is a strong indication that the Italian manuscript from which Robertet took the Latin verses, or a copy of it, was brought to France and was seen by others apart from Robertet. There is therefore no need to assume that Robertet saw these verses when he himself was in Italy.

If you read the Latin poems, it becomes clear that they were composed as an explanation for the accompanying images. .

Nathaniel wrote,

When I look at Trapp's quatrain for Death, I do not see any suggestion of victors standing on vanquished victims, albeit it is rather gruesome:First, they put a lot of stress on the fact that the figures are standing on their vanquished victims, as if the author felt that this was something unusual that needed justification (and of course, we know that it would indeed have been unusual in the context of Trionfi illustrations in Italy).

On the other hand, Robertet's huitain for Fame does suggest some such image - whether it presupposes it is another question - rather unusual for Fame (and not seen in any Italian version that I know of):Celibis abscindunt neruos et fila sorores

Nec durat fragilli vita pudica solo;

Sanior hac longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse sed heu! tandem singula morte cadunt.

The sisters cut off the sinews and fibers of the celibates

Nor does the frail life of chastity last alone;

Healthier than this long health celebs [?]

But alas! at last each one falls to his death.

Is Robertet simply continuing what he saw for Death, is he drawing on some French source - like tapestries - or has he been told of some Italian source of little influence in Italy? I have no idea. On the basis of what I have now, I'd go with the first, since we know he was in Italy before 1464 and there were mss. there most likely of that time period showing Death standing on someone's supine body (Vat.Barb. 3954 and the one in Naples). The Roberter publication date of ca. 1476 is reported in numerous sources, no one but you contesting it, on dubious grounds (that Robertet stimulated the French production of illustrated Trionfi mss., as opposed to the influx of Italian mss. after the French incursions).La Mort mort tout, mais Clere Renommée

Sur Mort triumphe et la tient deprimée

Dessoubz ses piedz. . . .

Death kills all, but Clere [Clear? Bright?] Renown

On Death triumphs and keeps her down

Under his/her feet. . . .

However, if there is a codex with quatrains in 1447 all talking about victors standing on or driving over their squashed victims, and if a copy of it got to France, that might explain better this major difference between the Italian illustrations - except a few Triumphs of Death - and some of the French tapestries and mss., of which the one with Robertet verses and his son's coat of arms is just one. And its verses might presuppose a ms. with images. But I'd have to see all the various verses.

This applies to the rest of what you say, too. Also, please tell us what relevant evidence Ziegler has, as this is a book I probably won't even be able to get via interlibrary loan, as it's very rare in U.S. libraries.

Last edited by mikeh on 18 Nov 2023, 08:41, edited 2 times in total.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

146You have to go to the Estense Digital Library. For some reason they have put two copies up. You can download it here: https://edl.cultura.gov.it/media/ricerc ... rds=u.7.24mikeh wrote: 20 Oct 2023, 23:27

I can't read them unless I can see them. When I get to the url in question (https://petrarch.mml.ox.ac.uk/manuscrip ... versitaria), all I see is "summary of the Triumphi in Latin elegiac couplets," without saying what they are, and nothing about quatrains.

The quatrains are as follows, on ff. 296v-297r. They have not been published before in full that I can find. They are in an independently paginated book containing the RVF and Trionfi, which was bound together with another one (at least) to form this codex, which was then numbered straight through. This is what the "old book" means in my note below.

alfa.U.7.24 ff. 296v-297r

(old book ff. 189v-190r)

Amor quatuor capitula

Ecce Coronati telo sternuntur amoris.

Cum Iove neptunus cum Iove pluto subit.

Lora voluptati reges imponite sceptra

Immoderata ruunt et moderata manent.

Pudicita capitulum unum

Arma pudicicie superando cupidinis arcum,

Hic dominum calcant, et sua tela premunt.

Nec pingui Cipro, nec molli floribus Yda,

In Cerere et Theti suppeditatur amor.

Mors tria capitula

Celibis abscidunt nervos et fila sorores,

Nec durat fragili vita pudica solo.

Sanior et longa poterit valitudine celebs

Esse, heu tandem singula morte cadunt.

Fama tria capitula

Omnia mors mordet, sed mortem fama triumphat.

Cetera mordentem, sub pede fama premit,

Egregium facinus post mortem suscitat ipsam

Nec scit Letheos limpida fama lacus.

Tempus capitulum unum

Tempore conculcor quantumlibet inclita fama

Me extingunt quamvis tempora sera piam

Quid prodest vixisse diu, cum fortiter evo.

Abdidit in latebris, iam mea tempus edax.

Iudicium capitulum unum

Ipsa triumphali prestans regina tropheo,

De veteri palmam tempore leta gero.

Rex, Amor, atque pudor, mors, fama, et tempus abibunt.

Felices animas Regia nostra tenent.

There are several transcriptions of the quatrains in Robertet's work, but I think with alfa.U.7.24 we can safely conclude that Robertet did not compose them, nor Jean Molinet (whose works also contain versions of them), nor any of these late 15th-early 16th century French poets. I am in complete agreement with Nathaniel that they come from no later than the early 1440s. They are copies, which is clear from the space the copyist left for the missing word "tela" in the quatrain for Chastity.

I also agree with Nathaniel that they are best understood as tituli of images, like those used for the viri illustres, and that therefore it implies there was a series of such images independent of, and probably earlier, than the Florentine style. From my limited knowledge, spelling of words like zoe for cioe, I'd guess that the ms. is from between Ferrara and Venice. It could well be Padua, which would link it even more closely to Petrarch and his immediate "literary executor," Lombardo della Seta. This is all to say that I think these quatrains are very old, perhaps going back to the late 14th century, which of course implies that the images do too. Besides Lombardo della Seta, I think Coluccio Salutati could be considered, since he also wrote tituli for a cycle of heroes. These are just guesses on my part, based on their association with Petrarch's legacy.

For transcriptions of the quatrains and his French poems, see Catherine Margaret Douglas, A Critical Edition of the Works of Jean and François Robertet (1962) https://repository.royalholloway.ac.uk/ ... 097849.pdf

Pages 459-465.

Douglas dates Jean Robertet's poem (not the images, note) to:

The first thing that struck me about the quatrains, and the copy of the Trionfi, is that the copyist calls it Iudicium, Judgment. He knows the other name, Eternitas, but prefers Judgment, since the text of the Triumph evokes this event at length. As far as I know this is unique to this manuscript.“about the same time as the Complaincte de la mort de Chastelain (1476) which, as we have seen, draws largely on the Trionfi for its display of erudition, and which in its philosophical ideas reflects Jean's preoccupation at that time with the Trionfi, and Petrarch's philosophy.” (page 201) Also, “It appears very probable that Jean Robertet introduced the adaptation in France of Petrarch's Trionfi in about 1476. ([note 3] The Complaincte de la morte de Chastelain, written in 1476, shows a close knowledge of the Trionfi, and a possibly greater understanding of their most important passage (from the point of view of their influence in France) than is found in Robertet's Triumphes. For this reason, the probability is that Robertet's Triumphes were composed at about this time, and before, rather than after, 1476.) Since Robertet reduced the Trionfi to an extremely short and simple sequence of ideas, with certain distinctive differences from Petrarch's long work ([note 4] the elimination of Laura's figure and the recurrent theme of love, for example), and since this same strict sense is found in the work of other poets written not long after Robertet's composition, it seems clear that Robertet rather than Petrarch was their immediate source.” (page 258)

“There exist two copies of this manuscript, H [BnF français 24461], H1 [Arsenal français 5066] and H2 [Chantilly, Musée Condy, 509], though perhaps only H1 is a copy at first hand. H3 [Chantilly, Musée Condy, 510] is also possibly affiliated to this group, but has several textual dissimilarities. It might be argued that all the manuscripts in this group, including H itself, might be copies of yet another, earlier, manuscript, now lost, but in view of the undisputably superior execution of H, expecially of the illustrations (and after all the illustrations have at least as great an importance in this type of collection as have the texts, and perhaps greater) it seems much more probable that H should be the original. This is borne out by the fact that many of the emblems, etc. have a precise reference to the house of Bourbon. What is more probable than that they should have been originally conceived and executed by François Robertet (in whose hand they are), who had some skill in design and draughtmanship, and was for a long time closely linked with the house of Bourbon?” (page 25)

“It should be said in conclusion about this group of manuscripts that the drawsings and texts in H and H1, at least, were intended as designs for tapestries (G [BnF, Nouvelles acquisitions française, 10262, dated 1514, not online], it may be remembered, contained some of the material of H under the heading “Autres dictz pour mectre en paincture ou tapisserie, et premierement les six triumphes de Petrarque faictz par feu maistre Jehan Robertet” “Other proverbs to put in painting or tapestry, and first the six Triumphs of Petrarch by the late master Jean Robert". One tapestry in the Victoria and Albert Museum shows that this intention was realised, for although different in the detail, it has the same basic design as the Triumph of Death in H.” (page 28)

“[At line 21] Robertet introduces the classical figures of the three Fates. These are not found in Petrarch's Triumph, where Death is represented by a single figure, but were to become general in France in representations of Death's Triumph.” (page 461)

f263r

La intencion di auctor e

exaltare Laura in questa opera

per la Castita, et fa il primo

Triumpho de l'amore che

vince ogni homo. El secondo

che Castita et pudicicia zoe Laura

con le vincono … Et

terzo e la Morte che vince lei.

El quarto e la fama che vince

la morte adar ad intendere che

che ben che la morisse niente de me

no el suo nome romase immortale.

El quinto del tempo che per longeza

obscura la fama. Ma il sexto

avegna che labra obscurate

el Iudicio difface lui et ogni cossa.

f.288v

Questo e l'ultimo Triumpho

zoe Judicio che vince ogni cossa

per elquale messer francesco mete Laura sia

in cielo, et parla a se stesso

Triumphus sextus

Eternitatis sive Judicis

It struck me because it has seemed to me that the Angel or Judgment card is more appropriate than the World, if we are looking for echoes of Petrarch. Visconti di Modrone even has the title on it - "Surgite ad Judicium."

The concepts of Resurrection to Judgment and Eternity are inseparable in any case. The earliest commentators on the Trionfi mention it explicitly.

See the commentary attributed to Francesco Filelfo, “Pseudo-Filelfo.” Printed by Andreas Portilia (thus the commentary is often called "chiose Portilia"), Parma, 1473.

https://www.digitalcollections.manchest ... CU-18977/7

1r

Pone anchora lo auctore nel fine di questa opera el sexto futuro triompho: el quale sera nel tempo del iudicio universale de la resurectione de le anime insema con li corpi glorificati.

The author also places in the end of this work the sixth future triumph: which will be in the time of the universal judgment of the resurrection of souls together with glorified bodies.

2v-3r

Lo Sexto: & ultimo triompho sie esso omnipotente: & eterno idio: il quale sopra ogni cossa: peroche in esso non e: ne cape alchun tempo: ne in lui ha possanza alchuna: anci el tempo e sottoposto a esso glorioso idio: e a petitione sua e questo: e ogni altra cossa creata: & maxime sopra del tempo venita ne la fine del mondo a iudicare li vivi: e li morti: cioe esso iesu christo figliolo de dio patre: del qual suo iudicio in lo sexto triompho se fara mentione.

The Sixth and final triumph is that of the omnipotent and eternal God, who is above all things, for in Him there is no beginning nor end of time, and [Time] has no power in Him. Rather, Time is subject to this glorious God, and at His will, both this and every other created thing are, especially above Time He that came at the end of the world, to judge the living and the dead. That is to say, Jesus Christ, Son of God the Father, whose judgment will be mentioned in this sixth triumph.

Compare Bernardo Ilicino's summary, written 1468-69: “Nela sexta & ultima demonstra al giudicio universale divino seguire la aeternita.”

(Commento delli triumphi del petrarcha composto per il prestantissimo philosopho Misser Bernardo da Monte Illicino da Siena. Pelegrino di Pasquali and Domenico Bertocho da Bologna, Venice, 1488, unnumbered folio 3v)

It is the Judgment that opens to Eternity.

It also struck me that the Regina of the final triumph, text and image, is best interpreted as Laura herself.

Re: Petrarca Trionfi poem motifs in early Trionfi decks

147Thanks Ross. I was not aware that the Estense had digitized the entire manuscript and made it available online (the two copies are probably due to the two different call numbers that Estense manuscripts usually have; the alfa one seems newer). It was not available online in January this year: I had to request an image of the relevant folios from them directly. They sent me a few more folios than I had requested, so it's likely that they took that opportunity to digitize the entire thing, and then eventually put it online. If only every library reacted like that to such requests!

Catherine Margaret Douglas is the same person as Margaret Zsuppán. She changed her name upon marrying. The work you linked to was her Masters thesis, done at London University in 1962; the 1970 book is largely identical to it. As you can see, her date of 1476 (and her Masters thesis is the ultimate source for this date in all other sources in which it is found) is based largely on Robertet's poem Complaincte de la morte de Chastelain, plus her mistaken belief that Robertet was the author of both the Latin quatrains and the French huitains. When the French huitains are viewed correctly—as an attempted translation of the Latin quatrains—there is no longer any good reason to think that they are likely to date to the time when Robertet first read and wrote about Petrarch's Trionfi. He must have written them after seeing the Latin quatrains, which could have happened at any time. Since we have no evidence, neither direct nor indirect, of the existence of the huitains before the 1490s, but quite a lot from that time onward, it seems sensible to assume that they were written around 1490 or so.

Robertet's translation of the quatrains is quite flawed. He makes several errors, no doubt due to the fact that the Latin of the quatrains is almost purely classical, to an impressive degree for the time—their author must have been quite thoroughly steeped in the works of Roman poets such as Virgil—whereas Robertet's own Latin was strictly medieval, as can be seen in his few surviving Latin works. There were several word meanings and phrases that he simply didn't grasp.

But his misunderstanding was not entirely his fault in one instance, at least. In both the Modena copy and in the manuscript he used, the wording of Chastity has what appears to be a miscorrection in the third line, which renders the last two lines of the stanza nonsensical. This is the "Nec ... nec", which must surely have originally been "Et ... et".

If this were so, those last two lines could be translated as "Both on lush Cyprus and on amorous Ida with its pleasant flowers—on both land and sea—Love is crushed underfoot." This was evidently the poet's take on the objects held in Chastity's hands: he chose to associate the palm frond with the isle of Cyprus and the sea, and the sprig of leaves and flowers with Mount Ida and land. Thus he makes them represent Chastity's dominion over Love in all places, even those where one would expect Love to be powerful: on Cyprus, the island devoted to Venus, and on Ida, described as mollis, a word which meant soft, yielding, pleasant, but which also carried connotations of lustfulness and amorousness. This is quite different from the usual meaning given to the palm frond of Chastity. The sprig of flowers, on the other hand, is usually shown in illustrations of the Triumph of Chastity simply a sprig of laurel leaves, with no flowers, symbolizing both victory and Laura herself.

The "nec ... nec" miscorrection had, I think, two causes. First, a failure to understand Ceres and Tethys as metonyms for the land and sea respectively, causing the copyist in question (obviously a copyist at an earlier stage of the copying chain than the Modena manuscript) to fail to see the intended meaning of these last two lines. The copyist could be forgiven for failing to understand this usage of Ceres, because it is the only thing I have spotted anywhere in the quatrains that is glaringly unclassical. The Roman authors used Ceres as a metonym for bread, grain, and food in general, but not land; perhaps the author could not find a more suitable goddess who fitted the meter. But Tethys, on the other hand, was often used by Roman poets to mean the sea. And if the copyist missed the meaning "both land and sea," then they might also have struggled to see why the poet would assert that Love would be defeated on Cyprus, the island of Venus.

The most immediate cause of the miscorrection, however, would have been the fact that "Et ... et" creates an apparent violation of the meter, due to Cipro et. Again, the problem here was probably the copyist's insufficient knowledge of Latin poetry. This metrical violation can be easily resolved by imposing a hiatus between Cipro and et, as this is exactly the kind of place where the Roman poets were most likely to use a hiatus, at the natural break in both the syntax and the sense of the line.

The introductory sentences in Latin at the top of each Trionfi page in ms 24461 are written in a very different, far less classical Latin, which even includes at least one calque from French, so Jean Robertet was probably the author of those. He may also have been the author of the concluding Latin couplets, which were not included by any other French author who copied either the Latin quatrains or Robertet's French verses.

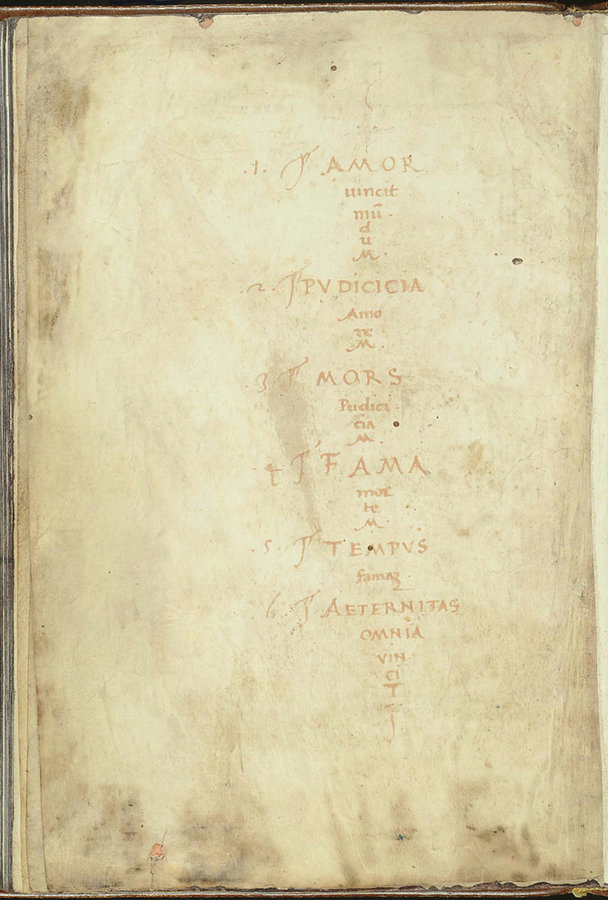

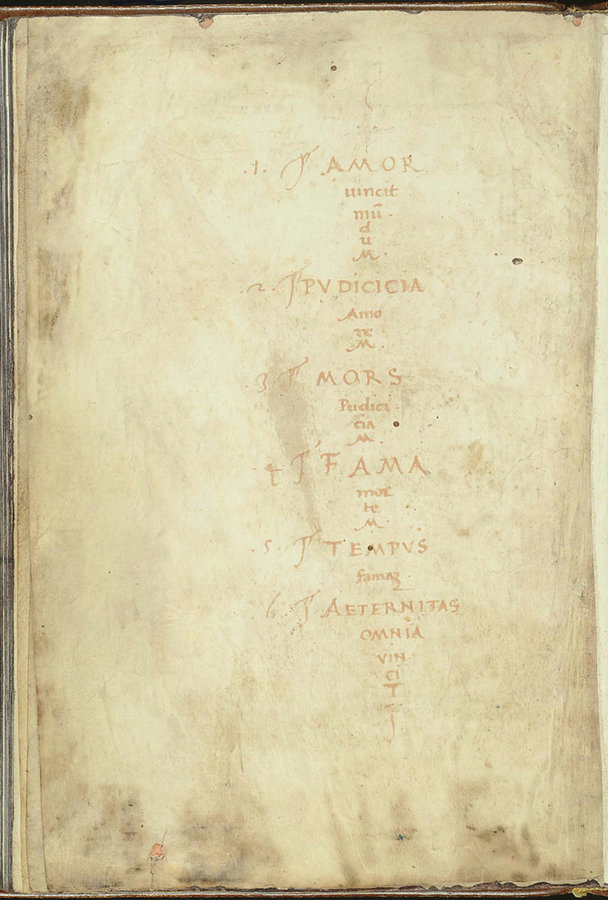

But importantly, he was definitely not the author of what I find myself thinking of as the "vincits", the short Latin phrases that follow each quatrain in ms. 24461: Amor vincit mundum, pudicicia vincit amorem, Mors vincit pudiciciam, Fama vincit mortem, Tempus vincit famam, Eternitas omnia vincit omnia superat. Another version of this appears in the other French manuscript I mentioned in my last post above, the two-volume Trionfi that includes the Latin quatrains in a wording closer to the Modena ms. than Robertet's. But there (f. 2r of ms. 5065) we see the phrases arranged in a vertical list, one below the other, and ending with Eternitas seu divinitas omnia vincit:

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b ... 8s/f7.item

These "vincits" appear in some form or other in many Italian Trionfi manuscripts of the 15th century. Sometimes the phrases appear separately in the Italian manuscripts, usually in the incipit of each Triumph, while sometimes they are assembled together on one page, either at the start or the end of the entire work, as in ms. 5065. I have counted at least twelve examples among the manuscripts I have seen, and I have not even been able to peruse most of the non-illuminated mss. because they are not online. It occurs so often, in fact, that it is not possible to be sure which of these two French versions is closer to the format that would have been in the Italian manuscript that was the source for Robertet's images. The copyist of ms. 5065 could conceivably have been imitating the format of the vincits in some other Italian manuscript that also made its way to France (although this admittedly seems unlikely), despite copying the quatrains relatively faithfully from the Italian manuscript used by Robertet.

I haven't yet done a thorough examination, and it has been a while since I looked at them, but I remember having the impression that the vertical list format is the older of the two, meaning that ms. 5065 is probably closer to Robertet's Italian source, just as it is in the wording of the quatrains. However, we can assume that the wording of the final vincit probably did not include the word divinitas, and may instead have been exactly as Robertet presents it. That wording, with its addition of omnia superat, is unique to Robertet's version (as far as I know!), but is readily explained by reference to the figures being placed on top of each other in the images.

These vincits go back a long way. I have seen a couple from the 1440s, and Strozzi 171 in the BML, which is dated relatively early in the second quarter of the 15th century, has amor vincit mundum in its incipit (I'm not sure if it has the other vincits also, as I am relying on the description on the Petrarch Exegesis website, but I would expect so). There is also a much rarer, alternative version with triumphat instead of vincit, which is possibly even older; the earliest dated example I know of is 1431, which uses the list format (which might be why I thought that format seemed older).

There are two points to make here:

1. The vincits mean that the manuscript Robertet was using definitely referred to the sixth Triumph as Eternity. Robertet does not call it Iudicium, and that word probably did not appear as a title for it anywhere in his source. I know of only three Italian manuscripts that use that title, other than the Modena ms. One is from 1469, another is merely dated "15th century," but Ross will be intrigued to learn that the remaining one is from the 14th century and probably from Venice.

However, the vast majority of Italian manuscripts in the 14th and 15th centuries refer to the sixth Triumph as Eternity. In light of that, and the fact that this is the only title given to it by Robertet, and that ms. 5065 does not use the title Iudicium either, we can fairly safely assume that the very first manuscript that contained Robertet's images would not have used that title for this triumph, and that it was simply applied by the compiler of the Modena manuscript, who was evidently at least two steps in the copying chain from that very first manuscript (because the copy they were working from must have had the miscorrected version of Chastity, with "nec ... nec", just as Robertet's did). That copyist possibly did not see the vincits that accompanied Robertet's version either, as they do not appear in the Modena manuscript.

It might also be worth pointing out that the marginal note in the Modena manuscript that introduces the quatrains makes them sound very much like a kind of optional extra that the copyist has just inserted into the manuscript because he thought it might be interesting, rather than an integral and ancient part of the work: Hec sunt quedam exposito[n]es super quolib[ro] triumphor[um] petrarce: (= These are some explanations about this book of Triumphs of Petrarch).

In other words, the Modena manuscript provides no good reason to deny the obvious conclusion that the female figure in the sixth Robertet image was meant to be Eternity, an anthropomorphic personification of the subject of that triumph, just like all the other five.

2. I can't help being struck by how much the vincits, with their beautifully simple and brutally direct structure, call to mind the action of the Trionfi card game. Even their semantic content makes you think of the game:

Amor vincit mundum - Love beats all the figures of this world, the kings, the queens, the other nobles, and all the ordinary mortals represented by the rank-and-file suit cards -

Pudicitia vincit amorem - Chastity beats Love -

and so forth, all the way up to

Eternitas vincit omnia - Eternity beats every other card in the game.

This could be just a coincidence, but it is a marvelous and beguiling one. Don't you think?

Catherine Margaret Douglas is the same person as Margaret Zsuppán. She changed her name upon marrying. The work you linked to was her Masters thesis, done at London University in 1962; the 1970 book is largely identical to it. As you can see, her date of 1476 (and her Masters thesis is the ultimate source for this date in all other sources in which it is found) is based largely on Robertet's poem Complaincte de la morte de Chastelain, plus her mistaken belief that Robertet was the author of both the Latin quatrains and the French huitains. When the French huitains are viewed correctly—as an attempted translation of the Latin quatrains—there is no longer any good reason to think that they are likely to date to the time when Robertet first read and wrote about Petrarch's Trionfi. He must have written them after seeing the Latin quatrains, which could have happened at any time. Since we have no evidence, neither direct nor indirect, of the existence of the huitains before the 1490s, but quite a lot from that time onward, it seems sensible to assume that they were written around 1490 or so.

Robertet's translation of the quatrains is quite flawed. He makes several errors, no doubt due to the fact that the Latin of the quatrains is almost purely classical, to an impressive degree for the time—their author must have been quite thoroughly steeped in the works of Roman poets such as Virgil—whereas Robertet's own Latin was strictly medieval, as can be seen in his few surviving Latin works. There were several word meanings and phrases that he simply didn't grasp.

But his misunderstanding was not entirely his fault in one instance, at least. In both the Modena copy and in the manuscript he used, the wording of Chastity has what appears to be a miscorrection in the third line, which renders the last two lines of the stanza nonsensical. This is the "Nec ... nec", which must surely have originally been "Et ... et".

If this were so, those last two lines could be translated as "Both on lush Cyprus and on amorous Ida with its pleasant flowers—on both land and sea—Love is crushed underfoot." This was evidently the poet's take on the objects held in Chastity's hands: he chose to associate the palm frond with the isle of Cyprus and the sea, and the sprig of leaves and flowers with Mount Ida and land. Thus he makes them represent Chastity's dominion over Love in all places, even those where one would expect Love to be powerful: on Cyprus, the island devoted to Venus, and on Ida, described as mollis, a word which meant soft, yielding, pleasant, but which also carried connotations of lustfulness and amorousness. This is quite different from the usual meaning given to the palm frond of Chastity. The sprig of flowers, on the other hand, is usually shown in illustrations of the Triumph of Chastity simply a sprig of laurel leaves, with no flowers, symbolizing both victory and Laura herself.

The "nec ... nec" miscorrection had, I think, two causes. First, a failure to understand Ceres and Tethys as metonyms for the land and sea respectively, causing the copyist in question (obviously a copyist at an earlier stage of the copying chain than the Modena manuscript) to fail to see the intended meaning of these last two lines. The copyist could be forgiven for failing to understand this usage of Ceres, because it is the only thing I have spotted anywhere in the quatrains that is glaringly unclassical. The Roman authors used Ceres as a metonym for bread, grain, and food in general, but not land; perhaps the author could not find a more suitable goddess who fitted the meter. But Tethys, on the other hand, was often used by Roman poets to mean the sea. And if the copyist missed the meaning "both land and sea," then they might also have struggled to see why the poet would assert that Love would be defeated on Cyprus, the island of Venus.

The most immediate cause of the miscorrection, however, would have been the fact that "Et ... et" creates an apparent violation of the meter, due to Cipro et. Again, the problem here was probably the copyist's insufficient knowledge of Latin poetry. This metrical violation can be easily resolved by imposing a hiatus between Cipro and et, as this is exactly the kind of place where the Roman poets were most likely to use a hiatus, at the natural break in both the syntax and the sense of the line.

The introductory sentences in Latin at the top of each Trionfi page in ms 24461 are written in a very different, far less classical Latin, which even includes at least one calque from French, so Jean Robertet was probably the author of those. He may also have been the author of the concluding Latin couplets, which were not included by any other French author who copied either the Latin quatrains or Robertet's French verses.

But importantly, he was definitely not the author of what I find myself thinking of as the "vincits", the short Latin phrases that follow each quatrain in ms. 24461: Amor vincit mundum, pudicicia vincit amorem, Mors vincit pudiciciam, Fama vincit mortem, Tempus vincit famam, Eternitas omnia vincit omnia superat. Another version of this appears in the other French manuscript I mentioned in my last post above, the two-volume Trionfi that includes the Latin quatrains in a wording closer to the Modena ms. than Robertet's. But there (f. 2r of ms. 5065) we see the phrases arranged in a vertical list, one below the other, and ending with Eternitas seu divinitas omnia vincit: