Online version of Delle Donne with images and transcription of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Urb. lat. 1185, folios 91r-99v -

http://web.unibas.it/bup/evt2/pantrionf ... rpretative

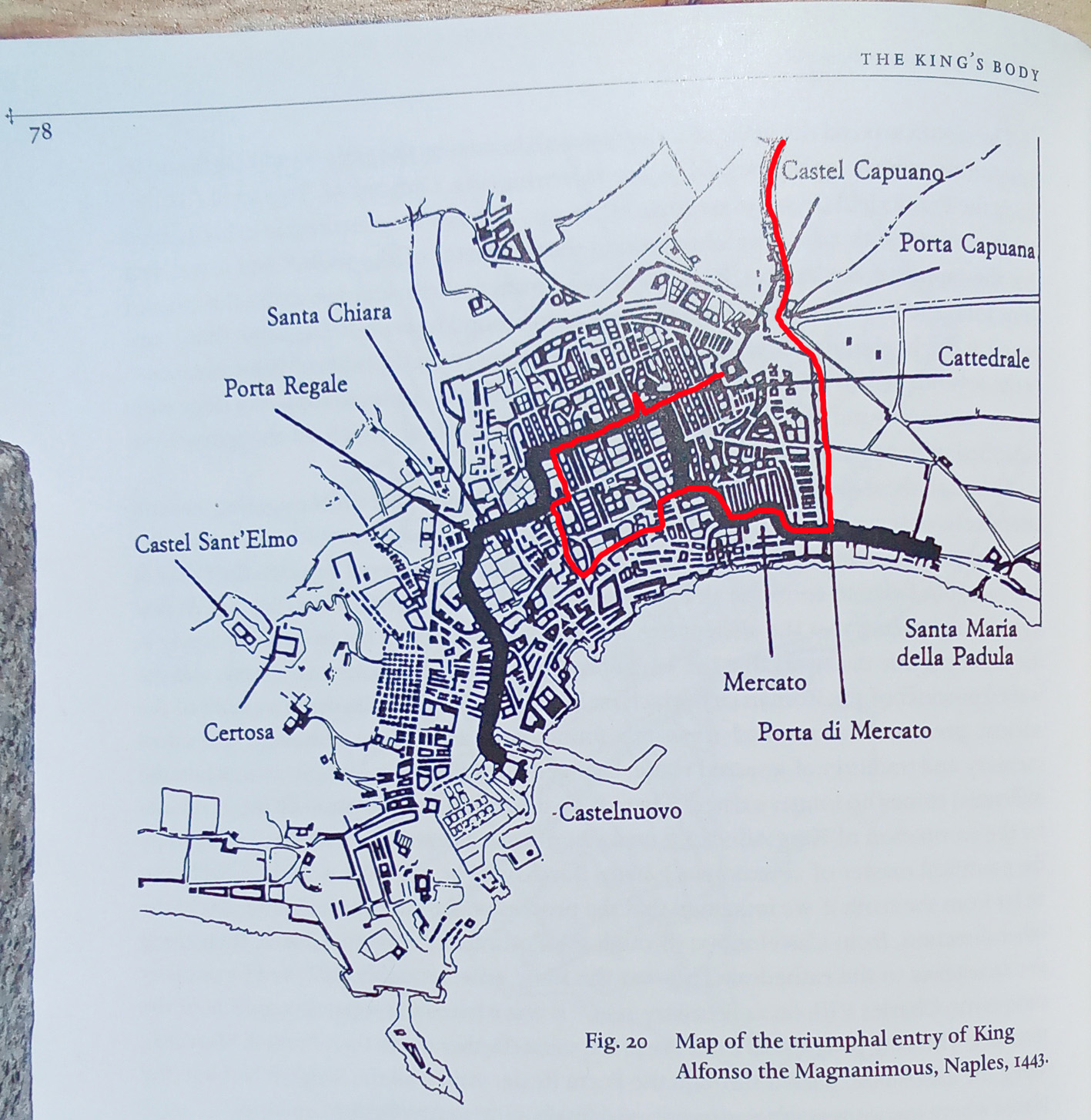

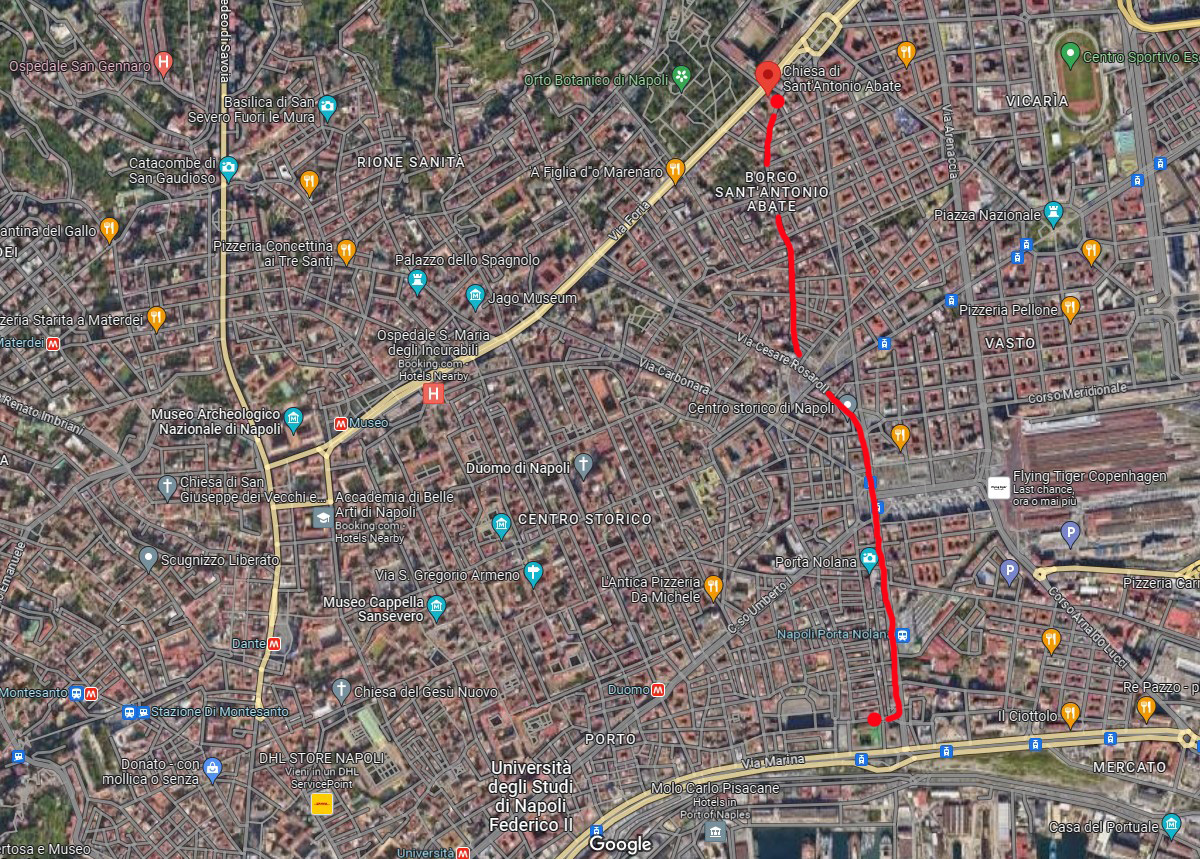

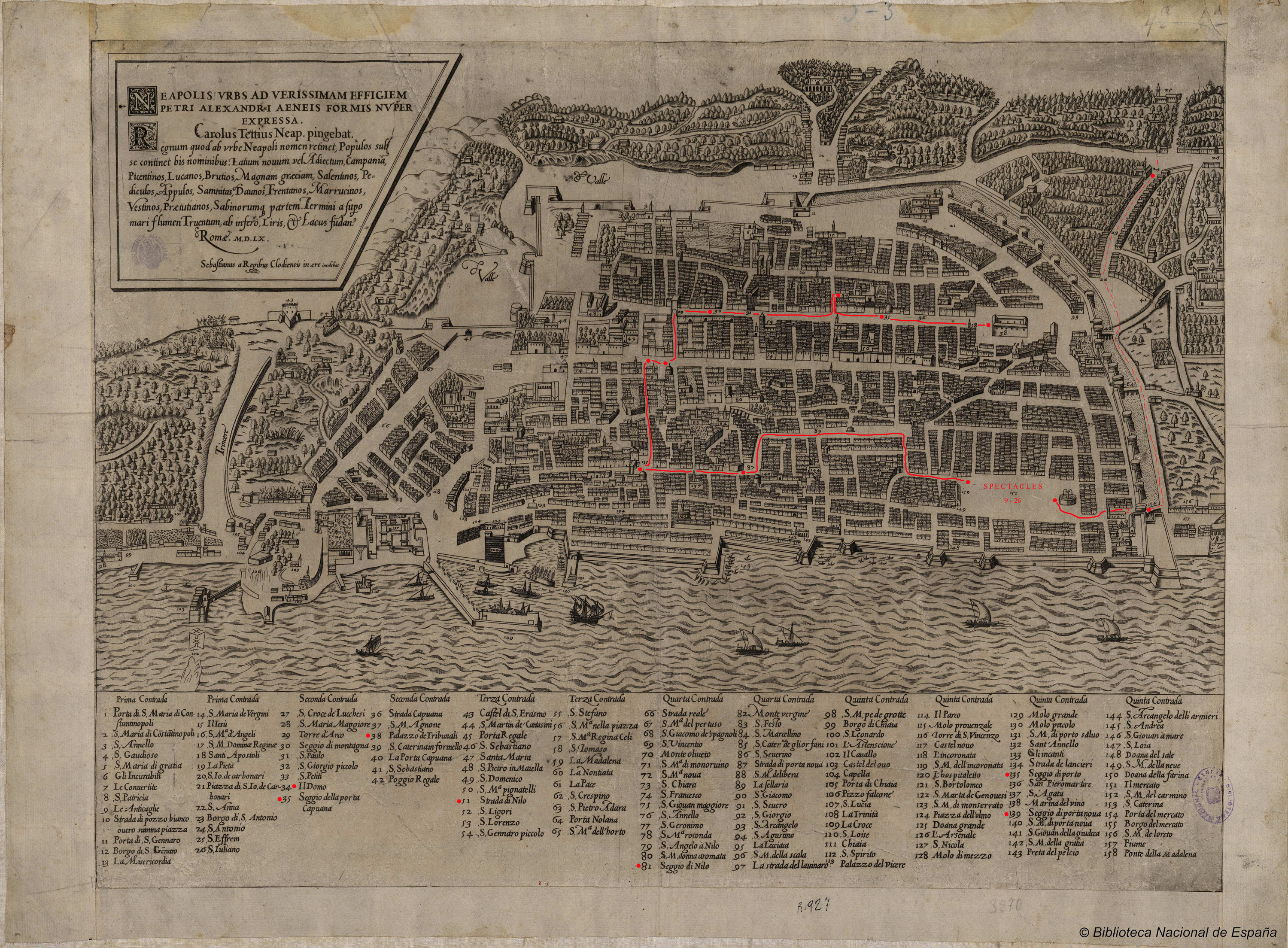

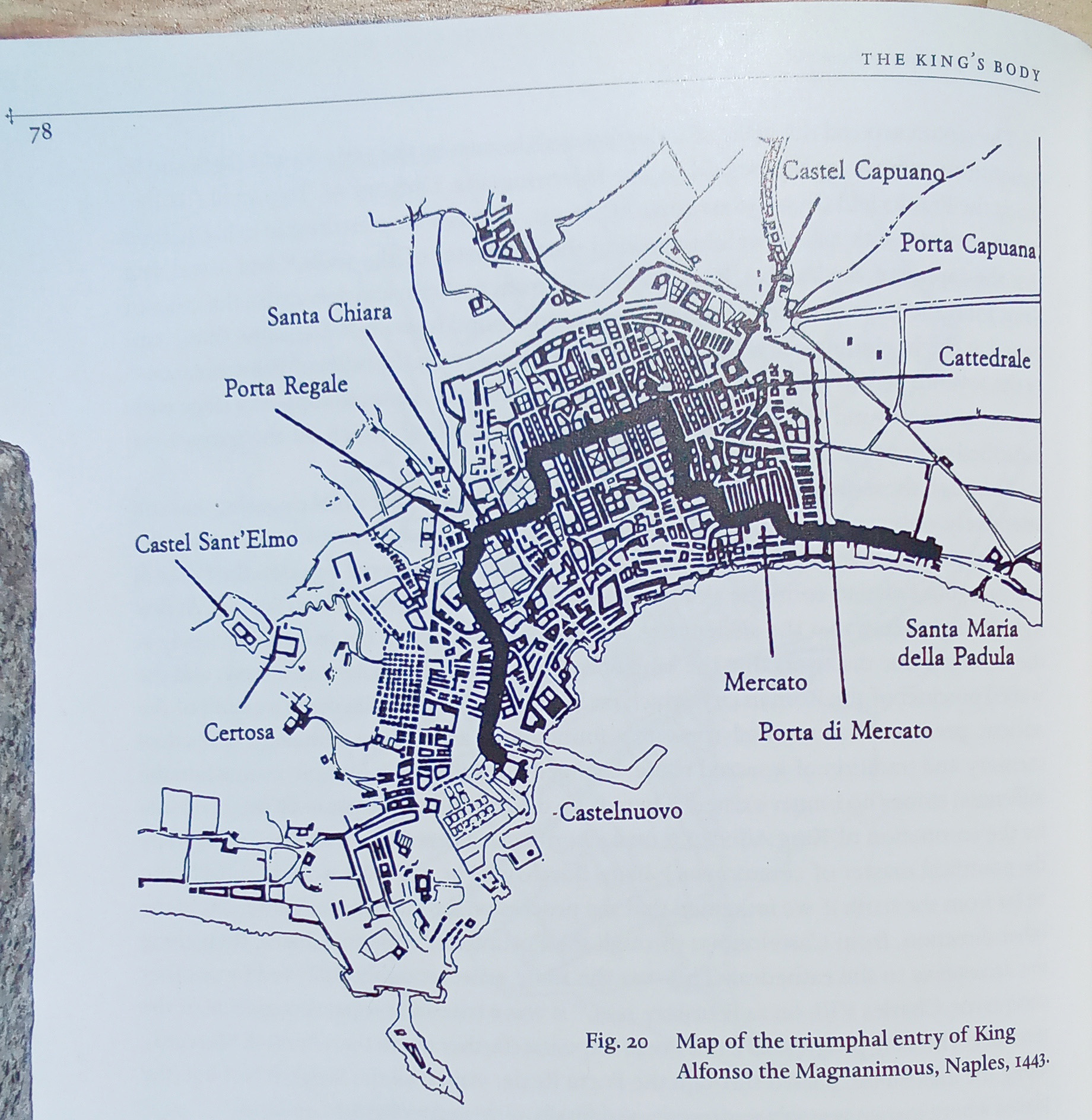

Map of Alfonso's triumphal route:

1) After the king and the princes of the Kingdom decided to celebrate the parliament in Naples, they left Benevento and first arrived in Aversa, then at the church of St. Anthony, located outside the walls of Naples, where they waited for a while as the necessary preparations for the triumphal spectacle were being made. In fact, all the citizens of Naples had unanimously decided to welcome the sovereign in triumph, both for the admirable victory of that king and for his exceptional clemency.

2) Therefore, on the 26th of February, the king appeared with the princes at the Carmine gate, near which a significant portion of the walls had been demolished by the citizens themselves to open a wide passage in honor of the entering king. There, the lofty triumphal chariot, entirely made of gold, was prepared, on top of which there was a throne made of gold and purple. Four white horses were attached to the chariot, each one pulling one of the four wheels, and they, quite fiery, were adorned with silk reins and golden bits.

3) On the chariot, in front of the king's throne, there was the dangerous chair that seemed to emit flames, certainly the most important among the king's insignia.

4) On the sides of the chariot, twenty nobles were arranged, and each of them held a high pole with the edges of a golden pallium tied at the top - never has it been heard that one equally precious has been used for such a purpose - from whose highest margins the emblems of the Kingdom and the city fluttered, elegantly hanging.

5) The king, sitting in triumph, was to be carried under this pallium, or if one prefers, umbrella, but before getting on the chariot, he decided to say or do something worthy. Thus, first calling Gerardo Gaspare d'Aquino to himself, he said: "I, young man, for your father's merits and services, appoint you and make you the Marquis of Pescara, and at the same time, I urge you to uphold his same faith, constancy, and integrity, for the honor of which we today bestow upon you such a high title, so that what has sprung from your father's benefaction, you may preserve and further amplify it with your own virtue. And you, Nicola Cantelmo, for the faith and respect you have shown, we make you the Duke of Sora, and you, Alfonso Cardona, for your outstanding military actions and singular virtue, we appoint you as the Count of Reggio.

6) With approximately the same words and the same gratitude in his heart, he elevated many others to the comital dignity: he made Francesco Pandone the Count of Venafro, Giovanni Sanseverino the Count of Tursi, Francesco the Count of Maratea, Amerigo the Count of Capaccio, all belonging to the same family. To many other highly deserving men, whom we avoid listing in order to move more quickly to more important and joyful matters, he then granted the equestrian dignity.

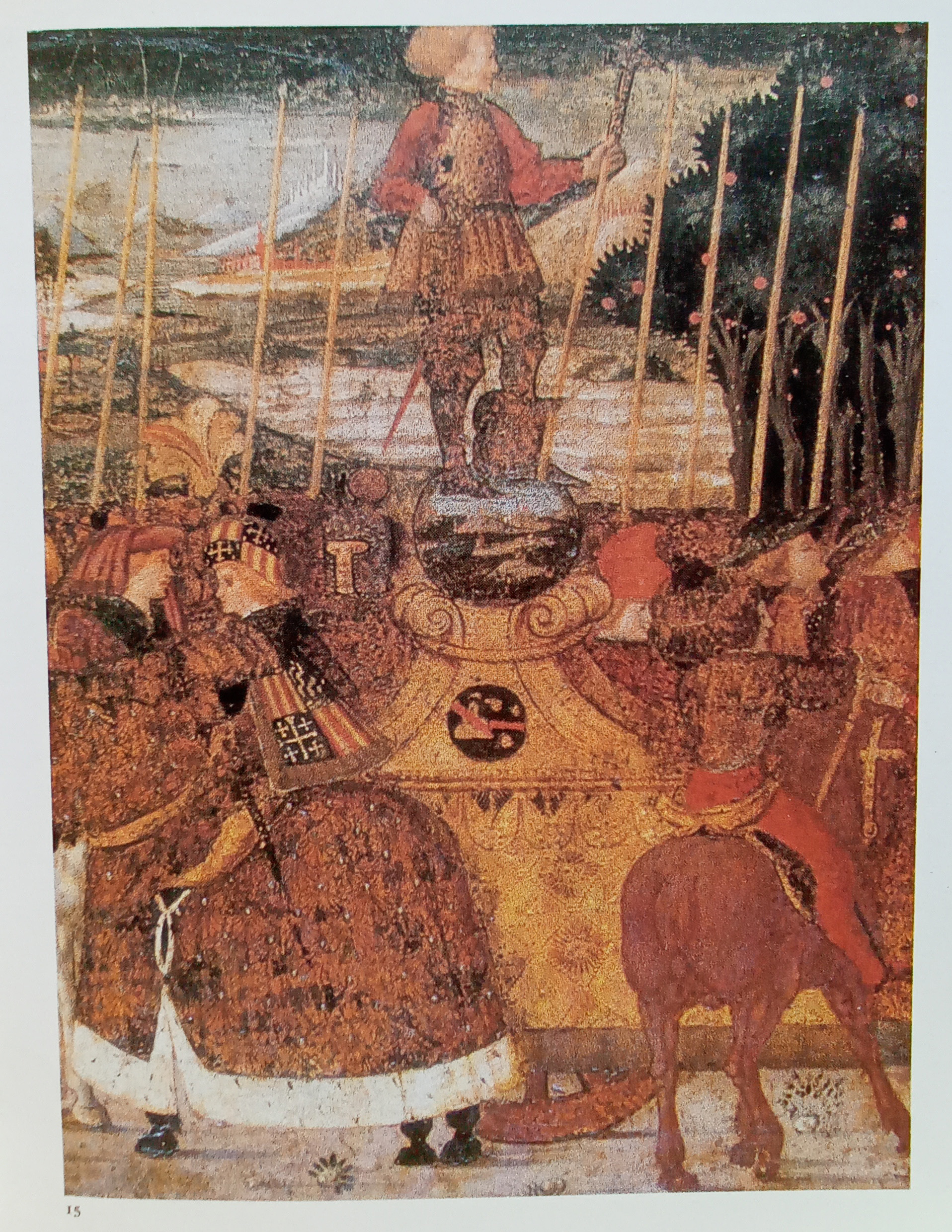

7) After these things, in the name of the true and most wise Christ of God, whom he always desired to give all praise and glory for the victory, he ascended the chariot, wearing a cloak of silk and scarlet, lined with sable fur in its long train, with his head uncovered. Indeed, although many, even noble ones, asked him to do so, he could not be persuaded to accept the laurel crown, according to the custom of those who celebrate triumphs. I believe this was due to his singular modesty and religiousness, as he judged that the crown should be bestowed upon God rather than any mortal.

8) But when he appeared high on the chariot, such great jubilation and applause arose from the men present and the women watching from the rooftops of the houses that, due to the clamor of those rejoicing, the blare of the trumpets and the sound of the pipes could not be heard, even though there were countless of them. Meanwhile, some could be seen crying tears of joy, others laughing with delight, and still others remaining astonished by the extraordinariness of the sight.

9) After proceeding a little further, he stopped until the procession that preceded him advanced, among whom the Florentines, foremost among all, presented various spectacles devised with singular ingenuity and executed at great expense, as follows.

10) Immediately after the trumpet and pipe players, ten children came forward, lined up in garments lined with scarlet silk, adorned with silver and pearls according to each one's ability to add them with their effort and devotion. They wore purple or, I might say vulgarly, scarlet shoes, ornamented in a manner very similar to their attire with silver and gems. Each of them rode exceptionally beautiful horses, which were also decked out with tinkling bells that resounded all around. Standing on the stirrups, in a way that barely touched the saddle with their backsides, in such a manner as to cause embarrassment to an honest person, they held a half-painted lance in their upraised right hand, adorned with various colorful flowers, which they would now twirl on their heads, now thrust forward as if to throw it, or, according to their pleasure, wave it. Each one had a crown made of gold leaf on their heads, and as they passed in front of the king, holding the reins with their left hand, they would bow their heads and lower the crown.

11) Following them was Fortune, the mistress of all things, on a platform covered with colorful carpets, and she was elevated as if on a high chariot, with long hair flowing down her forehead and a bald nape. Under her feet was a large golden sphere, and it was raised high by the arms of a child who appeared like an angel, and this angel had his feet immersed in water.

12) Shortly after, six virtues followed Fortune, carried on beautiful horses adorned with rich trappings, all of them possessing a most noble and ancient appearance. To be recognizable, each virtue carried its symbol in front of them. First among them, Hope displayed a crown, then Faith held a chalice, and Charity held a naked child. Fourth came Fortitude, who held a marble column in her hand. Fifth was Temperance, holding two vials and mixing water and wine. Finally, Prudence showed the people a mirror with her right hand and a serpent with her left.

13) Justice remained, as the queen of the others, not content with a horse, she was carried high on a pulpit, adorned and well-dressed. She held an unsheathed sword in her right hand and a balance in her left. Behind her, as if presenting the empire to those who followed and revered her, there was a throne placed higher, also decorated with gold and purple. On this throne, three angels seemed to descend from heaven, each offering their own crown to the one who deserved that throne through justice.

14) Following this beautiful throne was a great multitude of knights, dressed and styled in the fashion of various nations, princes, and nobles. However, they followed the throne in such a way as to precede a chariot carrying the personification of Caesar.

15) Indeed, Caesar came forward, carried on a highly decorated platform with steps covered by a carpet. Caesar stood there with a laurel crown on his head, in armor, and a mantle. In his right hand, he held a scepter, and in his left, a golden globe. Under his feet, the world, in its spherical form, rotated incessantly.

16) He stopped in front of Alfonso and spoke roughly in this manner, in rhythmic verses in the vernacular language: "Alfonso, most excellent among kings, I urge you to hold onto these seven virtues that you have just seen pass before you and that you have always cultivated until the end. If you do this—and I know you will—those virtues that now triumphantly show you to the people will one day make you worthy of that imperial throne, which you desired when it passed by. As you have seen, Justice was also brought with the throne so that you may understand that without justice, no one can achieve true and lasting glory.

17) But never rely on Fortune, who just now seemed to offer you her golden locks. She is fickle and unstable. Behold, the world is changeable, and everything is uncertain except for virtue. Therefore, revere it in the most religious manner, as you already do.

18) I will pray to the greatest and best God to preserve you in prosperity and Florence in liberty." After saying these things, Caesar mingled with the crowd, and behind him followed, in two rows, about sixty Florentines, all dressed in purple or scarlet tunics.

19) After them came those Iberians, whom we call Celtiberians in Latin and Catalans in the vernacular, and they also staged performances with a large number of people and an excellent spectacle. They had brought along some fake horses that closely resembled real and living ones, covered with trappings. Young men dressed in floor-length garments rode these horses, and as those young men moved their feet, it seemed as if the horses were truly galloping, turning, chasing, or fleeing. The riders held a shield painted with the king's insignia in their left hand and an unsheathed sword in their right.

20) Against them, there were foot soldiers dressed in Persian or Syrian fashion, fearsome with their turbans and scimitars. The horsemen and foot soldiers initially moved together, lightly dancing in harmony with the music and rhythms as if they were dancers. Then, as the music became more intense, they too became inflamed in battle, occasionally engaging in combat with the soldiers' loud clamor and the amusement of the onlookers. The Iberians scattered the barbarians in every direction, capturing and defeating them.

21) After them, a very tall tower beautifully adorned was carried, with an angel guarding its entrance, wielding a sword. On that tower, four virtues were presented: Magnanimity, Constancy, Clemency, and Liberality. They carried the dangerous chair, the royal emblem, each singing a song composed of different verses.

22) First among them, the angel addressed the king with verses that roughly said: "Alfonso, king of peace, I offer and entrust to your hand this castle with the four illustrious virtues above it. Since you have always revered and embraced them, now they willingly desire to accompany you in triumph."

23) Following, Magnanimity urged the king to display excellence of character, then showed the barbarians defeated and put to flight by the Iberians, so that the king would understand that, in the event he waged war against the infidels and those who do not acknowledge the name of Christ, the Iberians would immediately and undoubtedly emerge as victors.

24) Third was Constancy, the ornament of all virtues, and it too admonished to endure with a firm and unwavering spirit the circumstances of human life when they arise, to be guided by honorable and glorious intent without misfortunes, and to undoubtedly overcome fortune, enduring all things.

25) Then Clemency, with a countenance gentler than the others, gazed toward the king as if reflecting in a mirror and said, "These other sisters of mine, O king, certainly make you the best among mortals, but I make you equal not to men but to the immortal gods. They have shown you how to conquer, whereas I have always shown you how to pardon the defeated and reconcile them to you." Having briefly spoken these words, she fell silent.

26) Finally, Liberality threw coins to the crowd, demonstrating that the king should be content only with glory and leave all other things to the people.

27) After these remarkable performances, which took place in a marvelous manner in front of the chariot, five noble men dressed in scarlet capes appeared. One for each district: the entire city of Naples is indeed divided into five districts or squares, which they call "sedili" because people sit there. They went ahead of the chariot, directing it, staying to the right of the horses and organizing the crowd that preceded them, both with the sticks they held in their hands and, above all, with their formidable authority.

28) Therefore, Alfonso proceeded, venerable in his august majesty and admirable in the dignity of his entire person, and the applause of those who cheered him reached the heavens. All the barons and princes of the kingdom followed the chariot on foot, arranged in four ranks.

29) First among them were Ferdinand, the son of the triumphant Alfonso, a child of illustrious lineage, and Giovanni Antonio, the Prince of Taranto. Standing in the middle, to the right was Raimondo, the Prince of Salerno, and to the left was Abram, the envoy of the King of Tunis.

30) Then came Giovanni Antonio, the Duke of Sessa, an esteemed man worthy of eternal remembrance for his loyalty and steadfastness, Honored, the Count of Fondi, Francesco, the prefect of the city of Rome and the Count of Gravina, and Pietro, the envoy of the illustrious Duke of Milan.

31) In the third rank were Antonio, the Duke of San Marco, Troiano, the Duke of Melfi, Antonio Centelles, the Marquis of Crotone, and Giacomo, the son of the valorous Niccolò Piccinino.

32) Then, according to their rank, there were thirty-eight dukes and counts, about a hundred nobles and barons, an almost infinite number of knights, and a vast multitude of distinguished men, venerable prelates, and learned scholars.

33) Looking at the crowd behind the chariot, you could say that there were no other men in the city. Even that enormous square, as well as the rooftops of all the palaces, the windows, the doors, the arcades, the streets, the squares, and every other place were so filled with people, both foreigners who had come from all parts for the spectacle and citizens, that if you had not looked behind the chariot, you could have thought that there were no other men left.

34) And already Alfonso proceeded amidst the foundations of his triumphal arch, which had already begun to be built, and as he gradually looked at the various monuments, he started moving towards the district of the Mint, where the streets were strewn with flowers and foliage. But, an unprecedented sight neither seen nor read, the windows of the houses facing each other were connected with scarlet fabrics and woven abundantly with gold.

35) Under this almost golden sky, Alfonso, to the great applause of all the silversmiths and merchants, and with a new display of spectacles and festivities, carried forward in incredible celebration, arrived without further ado at the seat of Porta Nuova. There, an almost infinite multitude of men and beautiful women who danced and sang awaited the king with incredible longing and exceptional joy.

36) In this seat, as well as in the others, the walls were covered with colorful curtains and drapes, and the women were sumptuously adorned with purple, pure gold, and gems. That luxury was praiseworthy, as every elegant and refined thing was turned and dedicated to the king, the lord, the father, the benefactor.

37) Therefore, exhibiting, or rather interspersing, dances and songs, all the young maidens, kneeling with folded hands, adored him when they saw him as if he were a god, the guardian of their modesty. The men did the same because he had preserved their wealth and lives.

38) Then, advancing, he headed towards the seat called Porto, where the people engaged in similar dances and exultation, and which, with no less adornments, was extremely elegant in terms of the number, beauty, bearing, and refinement of the young maidens. They received the king with the same gratitude and reverence as their protector.

39) Then he was brought to Nido, a noble and ancient seat, not inferior to any of those already mentioned, whether you wanted to satiate yourself with the adornments of the walls and the beautiful paintings, or whether you wanted to be amazed by the multitude of maidens, or whether you wanted to be captivated by their beauty, or be caressed by their singing and delighted, perhaps, by their dances. Here, too, everyone rendered immortal thanks to the most pious and merciful king.

40) He was then brought to the ancient seat of Montagna, received by men and women with similar welcome, similar gratitude, and similar affection from all.

41) From there, he proceeded towards the marble steps of the cathedral, got off the chariot, and, accompanied by the procession of princes and nobles following him, entered the church and humbly prayed to the true deity, Jesus Christ, attributing and ascribing to Him the praise of victory, the glory of triumph, the honors of all virtues, and the gratitude.

42) Therefore, resuming the journey, in front of the church doors, he bestowed the equestrian title, for his merits, upon Giannotto Pitto; then he ascended the chariot with great and almost unbelievable joy and applause from the maidens who awaited the king in the seat of Capuana. Never before had there been greater refinement, whether in the magnificence of things, the beauty of similar maidens and nymphs, the generosity of the people, the grateful joy of their spirits, or, finally, in the individuals and the surroundings.

43) Continuing onwards, as evening was falling, the king was finally brought to Castel Capuano, which is located near this splendid seat. [Pietro Ursuleo]