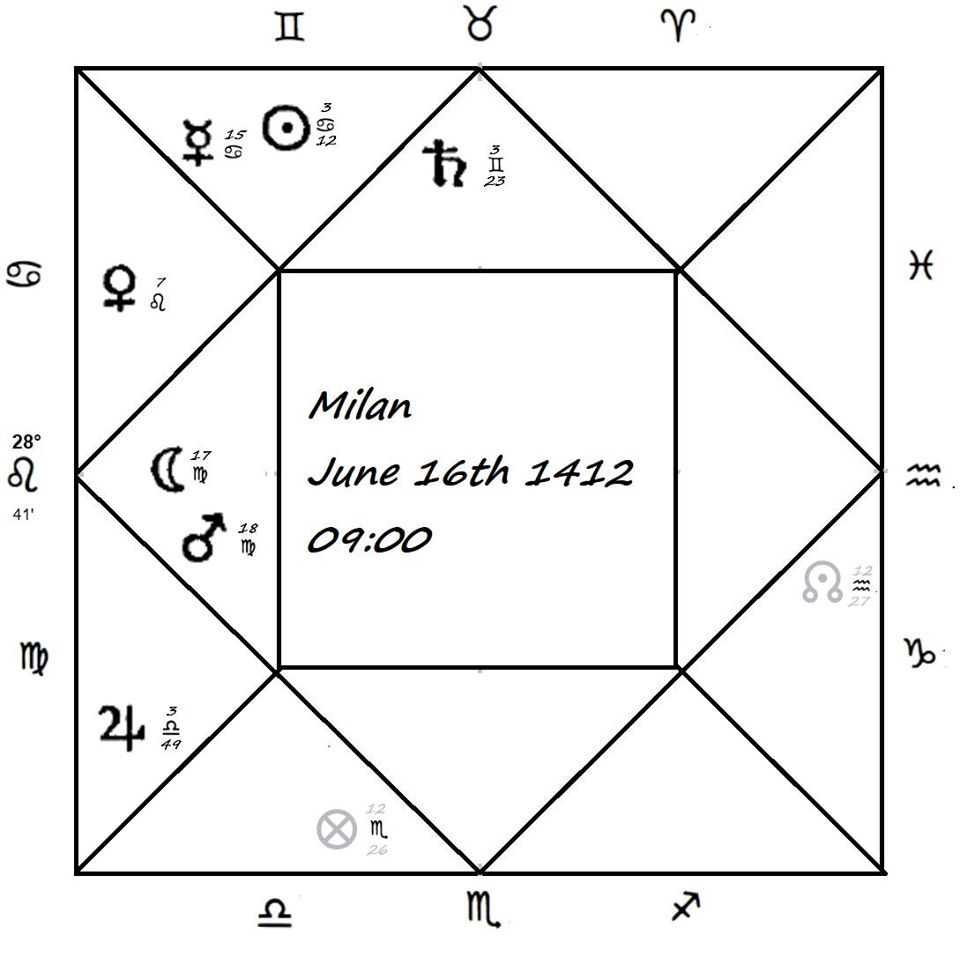

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote: 05 Apr 2020, 16:56

My confirmation bias is getting the better of me; I've found yet other reasons to prefer 1412, more precisely late 1412, for the composition of DSH.

Filippo Maria seems to have been profligate in spending in the early days....

If he were so profligate in his spending early on, this might help explain the huge sum of 1500 gold pieces (=ducati?) Decembrio says Filippo Maria paid for the DSH.

As I've stated, despite a lean towards 1418 I'm open to either that year or 1412, both having sound rationales:

1412: Filippo takes the Duchy and wants to assert his proper claims to it (e.g., continuing dear ol' dad's cultural works) but is forced to take the expedient measure of marrying Cane's widow, Beatrice.

1418: In the same year of his most recent dalliance with the Emperor for formal ducal recognition, that is postponed yet again, he has Beatrice executed. Now more than ever the dynastic claims in Giangaleazzo cultural works (e.g., the Visconti Hours) needed to be played up in lieu of imperial recognition. Part of placing the duchy on a sound footing is producing an heir.

In either case, part of the problem is Beatrice. Whether Filippo was actively trying or not, Beatrice does not produce an heir, and at all events Decembrio describes the match as "forced." So working towards common ground I have to ask:

do we agree Beatrice is a subtext behind Marziano's choice of deities, at least some of them?

My primary argument for Beatrice, the unsuitable widow , is that she parallels Dido in that regard - a dalliance for Aeneas (the grandfather of Anglus "Visconti"), that was but a distraction from his true destiny, which is what Beatrice would be for Filippo (whether or not he had moved on to someone else or not; e.g. Agnese).

The problem: Dido is not featured in Marziano. I've instead argued that the inclusion of Aeolus points to the series of events that blew Aeneas and his men from Sicily (home of Aeolus) to Dido. If Daphne is the chaste example that Filippo should be pursuing (like a flesh and blood Apollo - again, his radiant sun

impresa indicates that), then the negative example is Dido, but symbolized by the cosmic, and, natural even, force of wind that misdirected Aeneas to her (many humanists used the Latin

turbo - whirlwhind - and its variants to describe such fate-altering forces in their works, often in a negative sense). And Aeolus is inserted right before Daphne, arguably in contrast to her.

The evidence is the predilection of the Visconti to privilege the

Aeneid in their court since it speaks to their ethnogenic roots, and that Aeolus only occurs once there in the

Aeneid, therefore marking the aforementioned episode.

The only thing unique in Marziano's handling of 16 deities was his

fourfold approach of thematic suits, and thus we should we contextualize Aeolus. First, a word about the other three suits, starting with the two uncontroversial ones:

Virginities/Turtledoves: Pallas ,Diana, Vesta, Daphne - all virgins.

Pleasures/Doves: Venus, Bacchus, Ceres, Cupido - all related to the Epicurean pleasures of the flesh, as sex or food (or both in the case of Bacchus).

Next is more problematic as there is no Greek myth tying these four together:

Virtues/Eagles: Jove, Apollo, Mercury, Hercules.

However, the Virgilian myth of the

Aenieid does - Apollo is the tutelary god of Troy (yet another link between Aeneas/Anglus and the Visconti - the sun symbol), and in Book IV, lines 173-237,

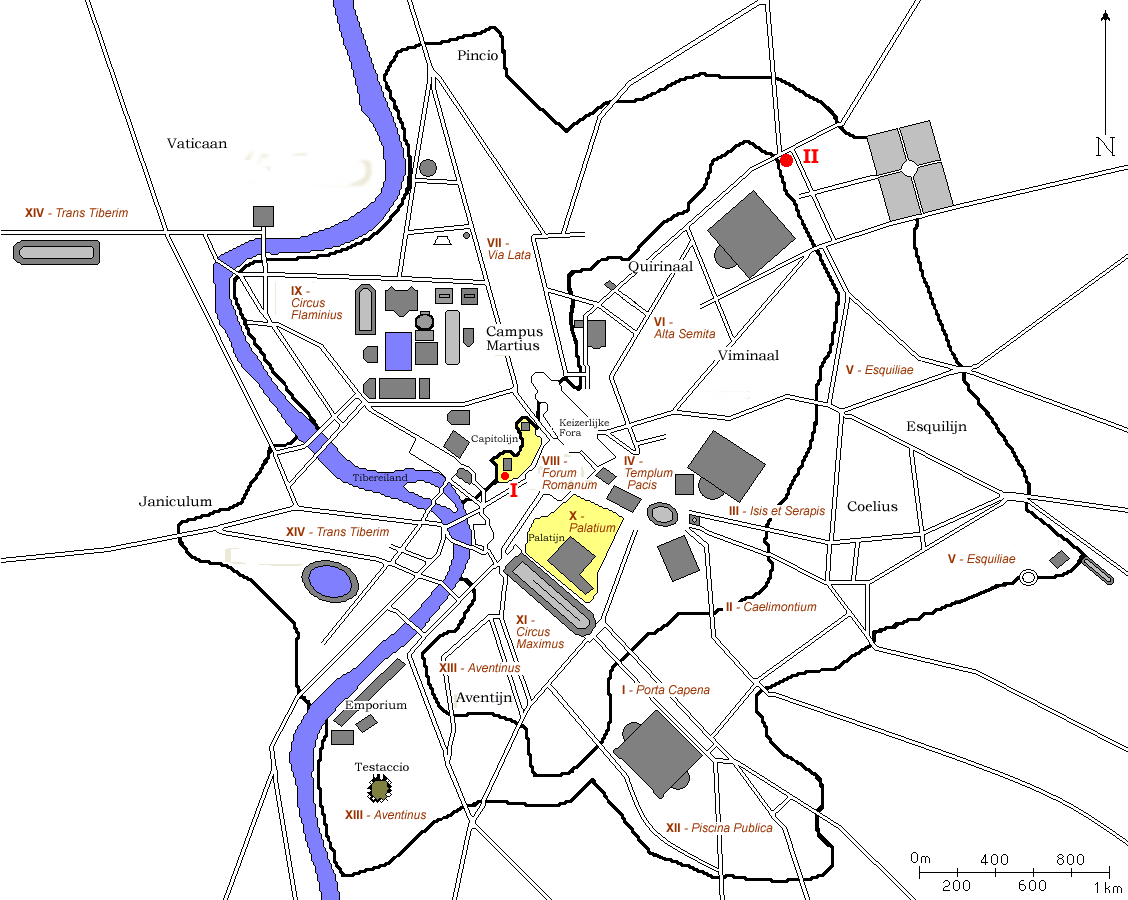

Fama spreads the word of the union between Dido and the Trojan Aeneas to which Jupiter sends Mercury to Aeneas to tell him to leave Carthage, for his destiny awaits him in Italy....where the way has already been cleared by Hercules (i.e., the Cacus/Aventine Hill episode that Marziano added to Hercules 12 labors, already discussed). And to put an exclamation point on these associations, Jove's eagle (Iovis āles), cuts through a sky made turbulent by other birds (

turbābat caelō, thus Jupiter cutting through Aeolus) to greet Aeneas when he enters Carthage (1.395-5). The "Virtues" then can all be linked Aeneas via either the Dido episode or his ultimate destiny in setting up the founding of Rome, of which Did was the primary diversion.

The most disparate collection of deities is where Aeolus himself has been placed:

Riches/Phoenixes: Juno, Neptune, Mars, Aeolus

Again, the same events in Aeneid surrounding the Dido episode in Carthage explains the selection of these four: Juno rouses Aeolus, who in turn upsets Neptune’s realm of the sea (Virgil notes Neptune is mad at Aeolus for this), which blows Aeneas detouring to Carthage, which he "escapes" to his ultimate destiny: the founding of Rome via Romulus and Remus (whose mother is a Vestal virgin), their father being Mars (involving the Aventine Hill, which we have already seen connected to Hercules by Marziano). Also noteworthy is that Aeneas meets Dido when she is in her temple for Juno. I would admit Mars is a bit of an outlier here - Juno-Neptune-Aeolus all being connected to the same scene - and not withstanding Romans are the "sons of Mars", Mars'

spoils of war was especially appropriate to the suit of riches, and thus he belongs here. Marziano actually mention that in his ipeoning line for Mars: "distinguished by so many spoils and chariots taken from the enemy," and later"promising the best rewards, both of riches and rich stipends." But all of that results from the functioning Roman Empire, set up by Aeneas.

But why is the Phoenix used for this suit of riches? Dido is "Sidonian" in Virgil, i.e., hailing from Sidon,

Phoenicia, the ethnicity of the Carthaginians (she in fact has founded Carthage).

The classical etymology for the word Phoenix was derived from Phoenicia due to phonetic similarities. Ovid specifically linking the mythical bird to “Assyria”, a term which included Syria proper, which in turn could stand for the older place name of Phoenicia, then become the Roman Province of Syria (her legions ultimately destroyed Jerusalem during the Jewish Revolt of 66–70 CE, so famously featured in the New Testament):

It seems likely that by Assyrians Ovid meant the Phoenicians, since in Classical times no great distinction was made between Phoenicia, Syria and Assyria, particularly by the poets. It may even be assumed that Ovid chose the word Assyrians for stylistic reasons, to avoid juxtaposition of the words Phoenices and phenica….Whereas Ovid seems to have thought that the bird owed its name to Phoenicia, Lactantius conveys the reverse. He states that the phoenix goes to Syria to die, and that this is how the region came to be called Phoencias. (R. Van den Broek, The Myth of the Phoenix: According to Classical and Early Christian Traditions, 1971: 52).

Lactantius, partially basing himself on Ovid, goes onto explain the bird builds it nest in a high palm tree that also owes it this name (Ovid leaves out the name part).

The whole story of the flight of the phoenix to Syria and its death there in a palm tree – which does not occur anywhere else in the phoenix literature – was developed by Lactantius [Narr. fab. Ovidianarum XV, 69-70] under the influence of Ovid [Met. XV, 396-397), from the homonymy of Greek words for phoenix, Phoencian, and palm.” (ibid, 52)

So associated was the Phoenix with the palm that in the SS. Cosmas and Damian church attached to the ruins of Rome’s fora, has within its 6th century apse mosaic a phoenix sitting atop a palm tree (Cosimo de Medici sent funds of the restoration of this namesake church)

https://roma-nonpertutti.com/storage/im ... b7c9e.jpeg

Isidore of Seville also connected the bird to the famous Phoenician reddish-purple (made from the murex shell found in the coast there) to the Phoenix, which became a commonplace reference (Isidore, Etymol., XII.7.22).

So we have the Phoenix connected to Dido’s homeland of Phoenicia (also "punic" as in The Punic War) in classical and early Christian sources, but Marziano most likely relied on Boccaccio, who not only makes all of the aforementioned connections, including naming Lactantius as a source, but links the genealogy of ‘Sidonian’ Dido to a Phoenician ancestor with the very name Phoenix:

And so for the Assyrians and Phoencians, for whom the reverence for Venus and Adonis was considerable….

…and as Lactantius says in his Divine Institutions, the Sacred History contains the report that [Venus] instituted the practice of prostitution….

As a long-lasting consequence of this, the Phoenicians gave their daughters over to prostitution before they married them off, [273-274] as Augustine bears witness in his City of God, and Justin in his Epitome of Pompeius Trogus, where describes on the Cypriot shore Dido had taken away seventy virgins who had come for profit.

Phoenix, as Lactanius says, was the son of Agenor…came with his brother Cadmus from Egyptian Thebes to Syria and ruled at Type and Sidon….

Eusebius explains that he as a skillful man because he first gave the Phoenician some letters and their shapes. Then for writing them he made vermillion, whence that color is also called ‘phoenician’ [pheniceus]; it is named, I believe, after the inventor of the color which later, with the letters changed, was called “punic” [puniceus].

Synchaeus, according to Theodontius, was the son of Philistine [which makes Phoenix the grandfather of Dido]. (Genealogia deorum gentilium, libri II.53-57., tr. Solomon, 2011: 273-77,).

Knowing his Boccaccio well, Marziano had every reason to link Dido with the Phoenix via her Phoenician roots.

I would also point out that Phoenicia, more often “Syria” in Roman sources, was a place of fabulous wealth. For a Roman senator to be assigned the Proconsulship ("governor") of Syria (annexed in 64 BC) was usually the apex of one’s career, such were it riches, with the spices of Arabia and India flowing through her. Syria’s capital of Antioch was one of the four largest cities of the Empire (along with Rome, Alexandria and eventually Constantinople), and her main luxury villa suburb named, oddly enough, Daphne, was “ the scene of an almost perpetual festival of vice.”

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/tex ... daphne-geo

Although descriptions of Roman Syria are anachronistic in regard to the Phoenicia of the

Aeneid (although written in early Roman imperial times of course), the geographical place had already become proverbially known as rich – references to the province in Roman literature would have only reinforced that trope; ergo, Dido hails from a place that is the embodiment of “riches”, the key attribute of the suit of Phoenixes.

Do all of these indirect allusions to the Aeneas-Dido episode in the Aeneid really point us to Beatrice Cane? Whom else could it possibly?

The ultimate problem then is finding a bride (a chaste Daphne, versus a widowed Dido) that could propagate the line of Anglus; would that need have been most acute in 1412 or 1418?

Phaeded