I’m finally going to start posting about the

“16 regions” format in Martianus Capella as an influence on Marziano, via Petrarch’s Africa….and for this first part focus on Barzizza’s reference to Laelius in the Eulogy as pointing to Petrarch as the inspiration for Marziano.

But first to rehearse how the idea first came up - in the discussion of Vesta:

Phaeded wrote

What is especially interesting here is what personal appeal Martianus Capella may have had for Marziano in that the Italian version of Martianus is Marziano (a sort of humanist pagan "patron saint" namesake). I've not mined Martianus's De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii for all of the Vesta references yet, but I did note that he divides "the whole sky into sixteen regions" - the same number of Marziano's deified heroes.

[Ross replied:]

I wish I had known of this sixteen regions of the heavens before writing the divination section! The literature on it is small…

Marziano would absolutely have known Martianus Capella. The De Nuptiis also mentions the Dii Consentes, equivalent to the Twelve Olympians, at the beginning of the section on the sixteen divisions with their very unusual selection of gods. See Shanzer's translation, linked below, and Weinstock's study ….

viewtopic.php?f=9&t=1426&start=50

Ross’s initial enthusiasm for the 16 connection to Capella has since waned, per the earlier reply in this thread: “The sixteen divisions, on the other hand, I'm not convinced by yet. There is just no comparison with the choices, so the number is a mere coincidence.”

A prefatory caveat for what follows, related to Ross’s complaint: Marziano’s exact list of 16 gods only approximates Petrarch’s list, who in turn does not follow Capella; all seem to have adapted the idea of 16 gods for their individual tasks at hand. In fact the ultimate Etruscan list of gods would have been lost to all involved, as the only two classical sources merely state how the heavens were divided into 16 regions – Cicero (

Div. 1.47), and Pliny (

NH 2.55.143), so no “ur-list” – like the

Dii Consentes - against which anyone could be checked against.

Capella lists several gods for each of his 16 regions of heavens, some bordering on obscure allegorical nonsense; e.g. from the ninth region of the sky comes “the genius of Juno of Hospitality” (1.53). Surely Shanzer is right in noting that Capella “is full of parody and allusions that are meant to be amusing and not to be taken too literally. I have my doubts about the famous “sixteen regions” passage so learnedly analysed by Weinstock; various details of this passage suggest that it is a parody of the traditional catalogue of deities” (Ross found this spot on quote in Danuta Shanzer,

A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella’s De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii, Book I, 1986: 11).

Before breaking down Petrarch’s text in a subsequent post, the Barzizza signpost indirectly linking Marziano to Petrarch....

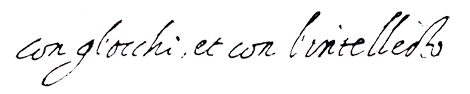

The senators admired [Marziano], some called him another Cato, others a Gaius Laelius. I truly tell you that when such things came under our leader’s judgement. He would whenever he was for a little while lifted from the cares of the realm, attentively hear this man’s most wise debates (Barizza eulogy, Ross tr.. 102-103).

As to the identification of these two Romans, Ross offered:

And this latter was Gaius Laelius the Younger, whom Cicero used as a character in several dialogues, the most important being De Amicitia, where Gaius Laelius is the main interlocutor. Gaius Laelius' father, Gaius Laelius the Elder, has no "speaking parts" in literature. The deep friendship between Cato and Gaius Laelius is a deliberate allusion on Barzizza's part, I am sure, poignantly emphasizing the friendship between Filippo Maria and Marziano.

Actually, Laelius the father does have a featured “speaking part” but its not in Cicero or any other classical source, but rather in Petrarch’s Africa; most relevant for the point at hand, is that it is Laelius the father, in Book 3 of the Africa, whose description of the Palace of Syphax - an adaptation of Martianus Cappell’s gods of the 16 deity regions of the skies. I’ve already pointed out that there seems to be a clue that Barzizza was referencing Marziano’s DHS in the eulogy and no reason he wouldn’t have thrown this learned tidbit in as well, referencing not just Marziano’s inspirational source but comparing him as well to the trusted second in command of Scipio Africanus.

And with the mentioning of Scipio, therein lies some of the confusion. For in Cicero’s

De Amicitia, although the deceased Cato the Elder is mentioned frequently, the dialogue is actually celebrating Laelius the son’s friendship with the deceased Scipio Aemilianus, aka Scipio Africanus Minor, or Scipio the Younger. The dialogue has nothing to do with the friendship of Cato and Gaius Laelius, but rather the latter's close friendship with the deceased Scipio Minor, as told to Laelius's two sons-in-law, Gaius Fannius, and Quintus Mucius Scaevola (Cicero knew this last). At all events, the context is Marziano’s abilities as an adviser, not friendship with Filippo (they are not peers, as say a Leonello d’Este would have been). Looking again at Barizza’s references to Cato and Gaius Laelius, we see that they are not referenced in terms of a dialogue, but individually by separate people, some thinking of Marziano as a Cato, others thinking of him as a Laelius. There is no suggestion of Cato’s relationship to Laelius.

Part of the problem with disentangling which Cato and Laelius is that those names are plagued with “parallel lives" who are relations. As will be argued, Barzzizza definitely has Cato the Younger and Gaius Laelius the Elder in mind, but first these historical Roman pairs, including the Scipio:

Cato the Elder – a curmudgeon paragon of parsimonious Roman virtue who was at odds with Scipio Africanus Major during the Second Punic War, although he served with him (and accordingly barely mentioned in Petrarch’s epic)

Cato the Younger – chip off the old block of his great-grandfather as curmudgeonly paragon of virtue, hero of Lucan’s

De Bello Civili/Pharsalia, and thus became the much bigger culture hero in the Middle Ages and Renaissance due to the enthusiastic reception of that work. Dante places this Cato, even though he committed suicide at Utica outside Carthage during Rome’s Civil Wars (hence his nickname

Uticensis) , as saved and as the guardian of mount Purgatory.

Scipio Africanus (Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, hereafter Africanus), the great victor at Zama over the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War, whose two main lieutenants were Gaius Laelius the father, and the local Numdiain ally, Masinissa, who both form the focus of the middle books of Petrarch’s

Africa (Syphax, allied with the Carthaginians, is Masinissa’s fellow Numdiian and ruler, but after the defeats in Spain, Masinissa defects to Scipio and ultimately made king of Numidia, living a long life all the way until Scipio Minor arrives for the Third Punic War).

Scipio Aemilianus, “Africa Minor,” is the one who defeated Carthage for good and famously sows its soil with salt. He was adopted by a son of Scipio Africanus, hence his adopted grandson who takes his cognomen of “Africanus” after he repeats his famous forebear’s feat of defeating Carthage (for the last time). This Africanus Minor and Gaius Laelius the son are in Cicero’s

Cato Maior de Senectute (Cato the Elder on Old Age) dialogue, where they are discussing old age at the end of Cato the Elder’s life (interestingly enough, not only are both the elder Africanus and Laelius mentioned, but as is Masinissa, who again, was still alive to host the younger Scipio and give battle again as an ally in the Third Punic War). Barzizza does not have that theme in mind in the Eulogy. More famously it this young Scipio who is featured in Cicero’s last book of his lost

Republic, saved via Macrobius’s commentary on the

Dream of Scipio, inspiring Dante and a host of other literary works. It is the younger Scipio and younger Laelius, being hosted by Masinissa on the eve of the campaign against Carthage, that the dream occurs in which Africanus Major shows the grandson Carthage from the sky and then the entire cosmos. So perhaps the most confusing point is that both Scipio Major and Minor have lieutenants named Gaius Laelius (father and son) when fighting Carthage, in different time periods/wars.

Gaius Laelius the father, as noted, is featured in Petrarch’s

Africa as Africanus Major’s right hand man. Besides his participation in battles, his most noteworthy deeds are first to align the Numidian King Syphax with Scipio, away from Carthage – it is during that diplomatic mission that Laelius describes Syphax’s palace’s hall via a long ekphrasis. Syphax reneges, but Laelius and Scipio still manage to turn Syphax’s number two in command (and cavalry leader), Masinissa to the Romans. Oddly the narrative focal point here is Syphax’s wife, Sophonisba, a Carthaginian noble woman, who turns Syphax away from Scipio, then leaves him and marries Masinissa, much to the concern of Scipio….who talks Masinissa into giving her up (and he sends her a cup of poison which she drinks). Despite the obvious echo,

Petrarch explicitly links Sophonisba to Dido. The Palace of Syphax in which we encounter the 16 regions of the heavens, Sophonisba's first husband and turncoat for the Carthaginians, then has heightened symbolism for an enemy of Rome (and why Marziano would have made serious changes to Petrarch’s list; more on that in a follow up reply). Masinissa and Sophonisba go on to be featured in the second

capitolo of Petrarch’s Triumph of Love (Scipio was equal to Laura as a lifelong obsession for Petrarch).

Gaius Laelius, the son (aka Sapiens), is with Scipio Minor right before the famous dream and aids him in all of his campaigns. While worthy of being a virtuous model in his own right, he obviously plays no role in Petrarch’s

Africa.

After sifting through all of the above, how can we be sure we have the right Cato and Laelius? The fundamental assumption driving my understanding of all things in Marziano, inclusive of the biographical words of a fellow humanist who apparently knew him well, is Marziano and Filippo’s literary relationship, per Decembrio’s

vita: Filippo preferred Petrarch above all else, and Marziano especially interpreted Dante for Filippo. In that light, Cato would be Cato the younger, one of the two pagans saved for salvation in the

Comedia (the other being Statius, not Virgil), playing the pivotal gate keeper from the inferno to Purgatory. Laelius in turn would be the opne associated with Scipio’s Africanus, the Elder, as his trusted lieutenant who plays the pivotal role in Books three and four revolving around Massassina and Sosophiba, the paralell to Dido, which we have uncovered as central to some of the

heroum in the DHS.

Oddly enough, Petrarch himself goes to some pains to distinguish between these “parallel lives”, in the

Africa itself (someone has translated the first four books, but without line references):

Eagerly embrace those friendships that Virtue brings about and nurture those that have just begun. Give friendship to those who ask. You will experience nothing greater in human dealings than the mutual intimacy and faithful heart of a friend. Indeed, a certain Laelius, truest of all, is with you now. May he know your secrets and be your aide. Let him earn your affection and peer into those depths of your heart that are concealed from the rest. After much time, your house will have a second Laelius. He will be dear to our famous descendent and will be likewise joined to him by a singular bond.”

“

In the future many will err concerning this. Laelius and Scipio alike will be celebrated as unique among all those friends whom the earth has produced since its very beginning, although they are two pairs, separated by a long period of time. (Petarch,

Africa, Book II. p. 40:

https://baylor-ir.tdl.org/bitstream/han ... sAllowed=y )

Barizza’s was himself largely indebted to Seneca’s letters to Lucullus, which features Cato the younger as the exemplary role model, making that Cato all the more likely. Barzizza’s lectures on the

Epistolae Morales of Seneca (aka “letters to Lucullus”) - his voluntary lectures - were based on his feelings that “the

Epistolae Morales ad Lucilium were the product of the greatest moral philosopher in antiquity” (R. G. G. Mercer,

The Teaching of Gasparino Barzizza: With Special Reference to His Place in Paduan Humanism, 1979: 43). Barizza was certainly one of the foremost Ciceronians of his day as well, and Laelius the son also exemplary for him, but there is only so much we can derive from Barzizza’s personal preferences – he was talking about the regard that Marziano was held in Milan. Given the special connection of Dante between Marziano and Filippo, Cato must be the Elder. Certainly Marziano’s DHS, which resulted in such a prestigiously expensive commission for Besozzo, made the work known to Barzizza and hence his selection of noting Laelius, which must be the one featured in Petrarch, who in turn has

that Laeloius describe the 16 regions of the sky in Syphax’s palace.

It bears to mention Petrarch was not a passing fancy of Filippo but a central feather in the cap of the Visconti court, living in Milan for 8 years from 1353 until 1361, and linked, however vaguely, to the dynasty’s motto of

a bon droyt. Moreover, Petrarch in effect made himself a sponsor of the ethnogenic project right after he moved there when he agreed to be Bernabo Visconti’s first male born’s godfather in late November 1353, even writing a poem of the occasion (Ernest Hatch Wilkins,

Petrarch's Eight Years in Milan, 1958: 45). Petrarch also expanded his

De Viris Illustribus while in Milan for an expanded life of Scipio (naturally related to his on-going

Africa), and after his death unknowingly continued to play a role in Milan when Visconti conquered Padua and took Petrarch’s library to Pavia to form the nucleus of the ducal library there, undoubtedly the most renown one outside of France (particularly worthy was the

Virgilio Ambrosiano Petrarca, , duly copied 1393/94 apparently for distribution and circulation; ibid, 33). Again, this is just not a personal obsession of Filippo’s, but a dynastic one.

For the

Virgilio Ambrosiano Petrarca:

https://www.ambrosiana.it/en/opere/the- ... petrarca/

So through the lens of the Marziano-Fillipo relationship, humanist adviser to Anglus-derived prince, naturally Petrarch’s prominent use of a Laelius in Africa would suggest that Laeiulis. Laelius in turn describes the 16 heavenly regions employed by Petrarch. What Marziano would have done is resurrect that idea in terms of the Visconti ethnogenic project – how do the Visconti fit within a genealogical scheme of

heroum? How does Filippo specifically participate in that scheme? If c. 1412, not with a whole lot of gusto, ergo the Aeneid-Dido myth into the game, strongly echoed in Petrarch's

Africa in the figure of Sophonisba, first married to Syphax.

Finally, the publication date of Petrarch’s jealously guarded

Africa – its “fortune” - not released in his lifetime, also supports the hypothesis of it being the idea for Marziano’s 16 gods. The text was finally made public by Pier Paolo Vergerio in 1396-1397, “published” in the latter year, so only 15 years prior to Marzian’s hypothetical date of c. 1412, thus still relatively “fresh” as a literary sensation. Scholars like to point out how little influence the

Africa had but that is only in the context of the rediscovery of Silius Italicus's epic poem

Punica, also about the Second Punic War, found in either 1416 or 1417 by Poggio Bracciolini, effectively superseding Petrarch as a “source” for that Roman period (nevertheless, even a date of c.1418 works for my theory as the

Punica would still have needed to have been copied and circulated, and initially it might have only sparked renewed interest in Petrarch’s work for the reasons already noted, but again, I am now leaning towards c. 1412).

My next reply will deal in detail with Petrarch’s Palace of Syphax episode in Book III, but first want to see if there will be any discussion of what has been presented so far.

Phaeded