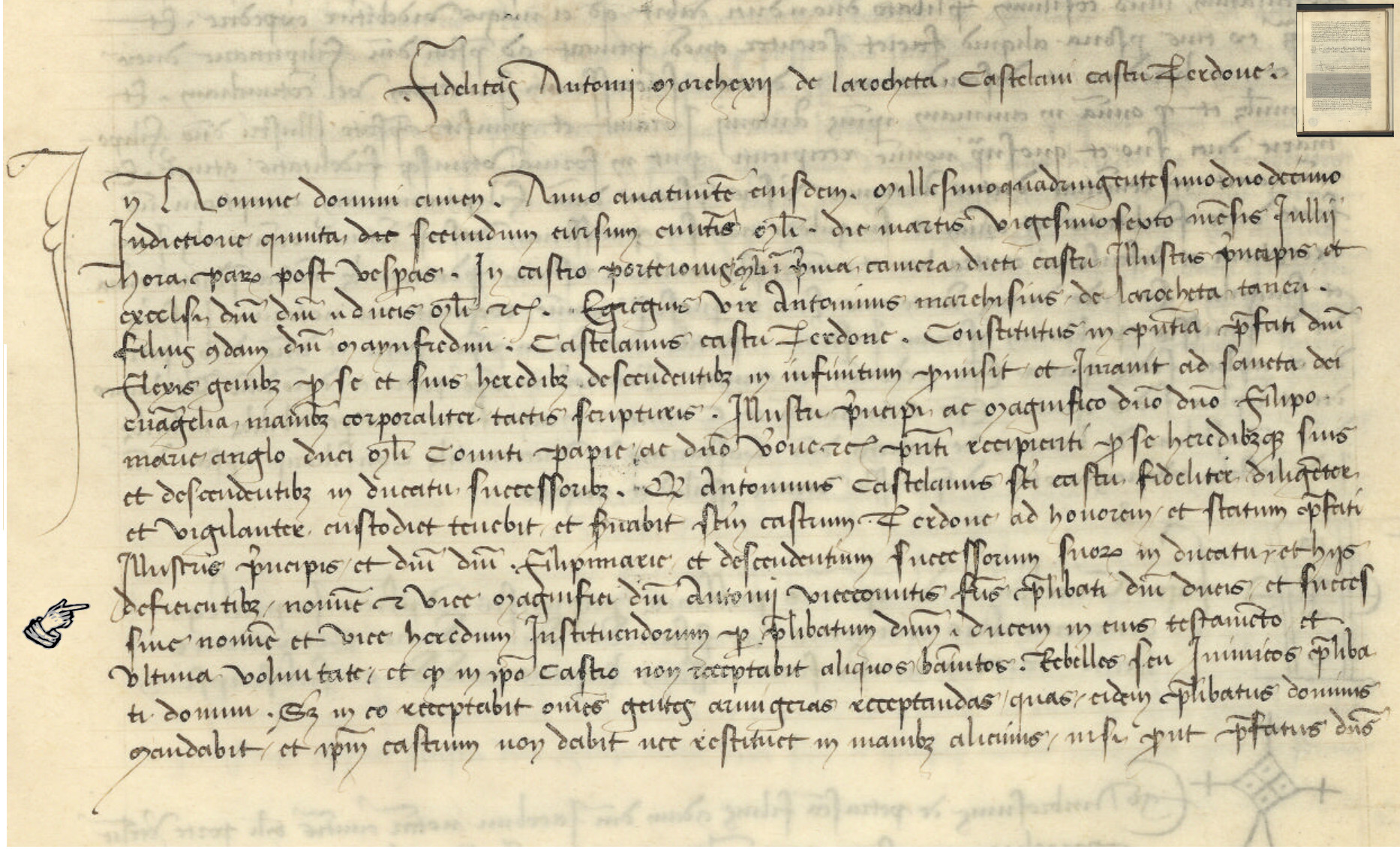

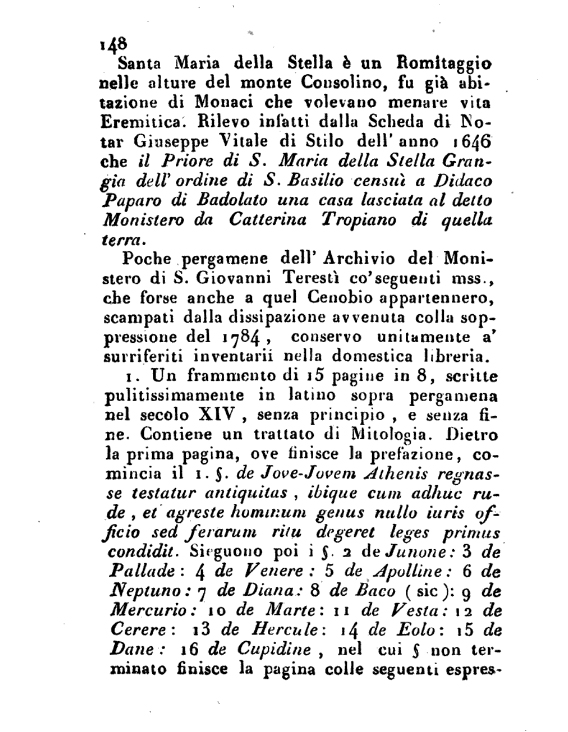

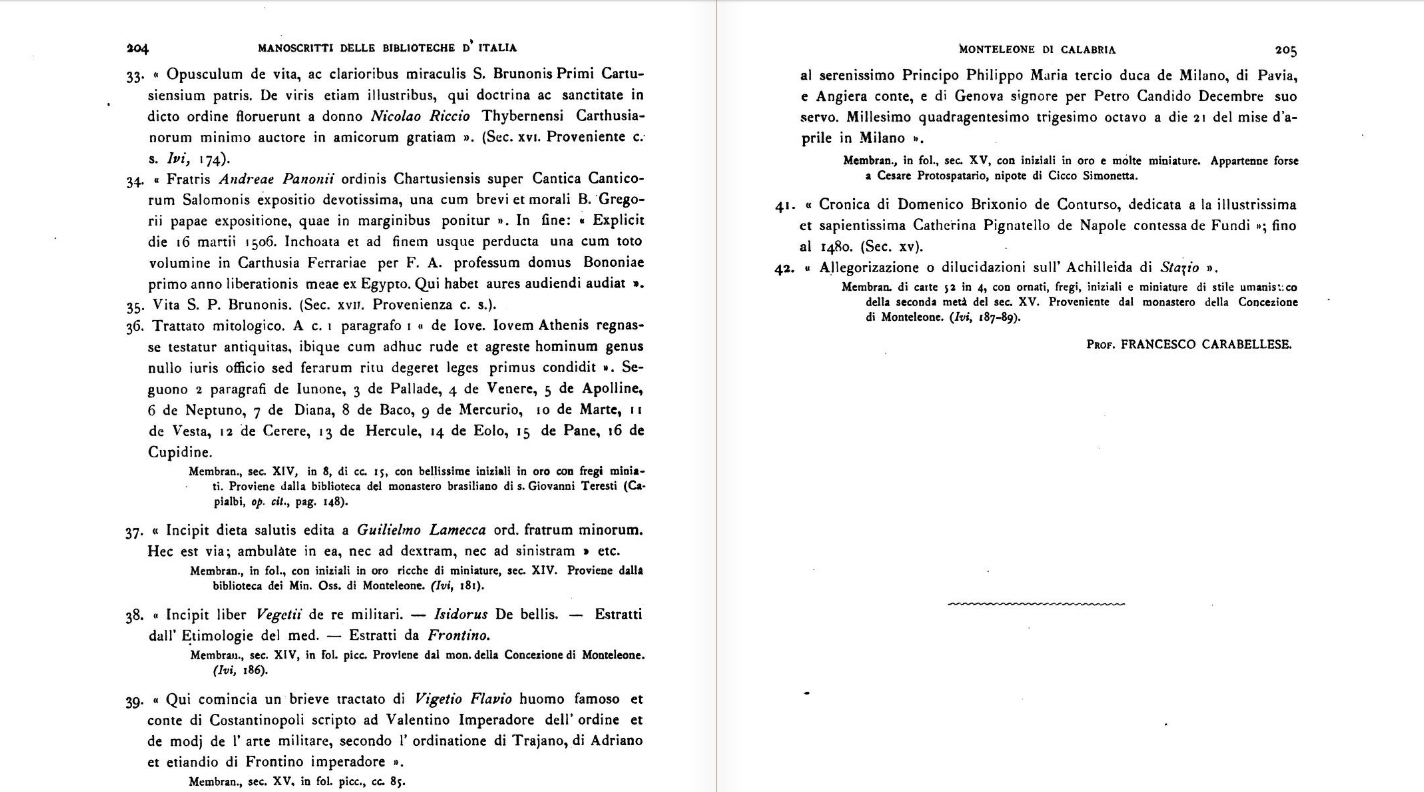

Instead of continuing the casting about for the sources that may have influenced Marziano, should we perhaps let Filippo’s own interests weigh in here as the decisive influence in Marziano's arrangement of gods and goddesses (and a naiad)? After all, Marziano had a market of one person. Thankfully Decembrio provides the basics of what we need to know here:

Filippo’s core curriculum in literature consisted of the sonnets of Petrarch, written in Italian verse. The young man was so affected by his reading of these poems that when he became duke he insisted that someone in his entourage be designated to comment on and elucidate them [Ianziti notes Decembrio did this himself as well as provided a life of Petrarch, but I would also note Filelfo also provided extensive commentary of the canzoniere, at the duke’s request] . And it was he himself who established the order in which he wanted the sonnets to be read. He also listed with the greatest attention to Marziano da Tortona, whose lectures focused on the vernacular works of Dante. He listened to readings from Livy as well, but in no particular order, preferring rather to select the highlights…. (vita 62, Ianziti 125).

Knowing his prince well, for a project that focused on the classical

heroum, surely Marziano wouldn’t have left out the mytho-poetic essence of Petrarch in the conceiving of his deck, nor his own personal connection with Filippo through his readings of Dante, especially the rich vein of classical material in the latter’s most famous vernacular work, the

Comedia.

I’d like to frame the ensuing discussion by noting that the inclusion of the naiad Daphne into the deck, the least divine of all 16 “heroes”, is clearly a nod to Petrarch, who would mediated all classical sources in regard to her (such as Ovid) for Filippo.

Daphne was of course the poetical stand-in for Laura, Petrarch’s proclaimed love interest who died young and was praised to the stars as much as Dante’s deceased Beatrice. Regarding her pivotal role in his

trionfi:

But the archetypal image is the myth of Apollo and Daphne, for which we have essentially discovered in these particular verses of the last ‘Triumph’ is the ultimate power of the poet-Apollo who, having faced the inevitable loss of his beloved, decides to perpetuate her memory through his divine powers by proclaiming the eternal verdure of laurel-Laura, and sanctifying its coronation of human achievements. (Aldo S. Bernardo, Petrarch, Laura, and the Triumphs. 1974: 143, but Daphne figures throughout - Bernardo has 25 references to her in his index )

But Decembrio points us to Filippo's love of the sonnets, not the

trionfi (but as just noted above, the trionfi hardly conflict with the Daphne thesis). To wit, in the longest of Petrarch’s

canzoniere, 23, the poet himself undergoes Daphne’s transformation:

What a state I was in when I first realized / the transfiguration of my person /and saw my hair formed of those leaves / that I had hoped might yet crown me.

The illuminations of Petrarchan manuscripts show the author with Laura almost always in connection with the laurel tree from the Daphne myth. Moreover, significantly in terms of Daphne and Cupid forming the pair that terminates Marziano’s list of gods, is the presence of the Goddess of Love’s son, or at least his arrow, in many of these illuminations. This became the primary way in which to portray Petrarch (and no doubt why all "Three Crowns" are always shown with laurel crowns, due to Petrarch's obsession with Laura/laurel-Daphne):

Despite the apparent incongruity of the virginity of Daphne, the key takeaway from Petrarch is she has a human cognate, a flesh and blood woman, Laura, whom he was smitten with before she died (and then said love was sublimated into unending poetry). Any argument that Daphne is not a representative of Filippo’s own potential love interests, due to her chastity, would need to discount why Petrarch would not matter here, which would fly in the face of Decembrio’s explicit statement that Filippo was most affected by Petrarch, which in a word, is the human

Laura. Moreover, given the presence of Cupid and/or his arrows in the several representations of Petrarch with Laura, one can interpret the presence of Daphne in Marziano's deck as related to Filippo’s own impulses towards a consort or would-be consort (either the problem that he was not going to have children with Beatrice, pre-1418, or when he was between marriages, post-1418). To quote Marziano on Cupid’s mother again.

Some among the ancients said that Venus was pleasure … Although it was not of this sort of pleasure that such an honorable man discussed, but of that preferable pleasure which seemed to follow virtuous acts. (Caldwell translation, 2019: 40-41).

What is this virtuous act is not making an "honest woman" out of the beloved, i,e., marriage?

In other words, Marziano takes a “Petrarchan” tact here in recognizing Venus, but tempers enthusiasm for her through the prism of virginity/virtue (which to my mind connotes a chaste bride, only deflowered after the virtuous act of marriage; Petrarch's own carnal urges are confused from from the point of view of a quasi-cleric's unrequited longing).

From that reference to Venus, we can segue back to the ethnogenic project: Filippo’s descent from Aeneas and Anglus, via Anchises-Venus. As noted by Decembrio, Marziano’s special literary connection to Filippo was Dante, and Dante’s most famous endeavor is specifically modeled on that original ethnogenic project: Virigil’s recounting of the divine descent of Octavius/Augustus from Venus, especially

in Book VI of the Aeneid. In that book Aeneas descends into Hades, with the Sibyl in tow, and encounters his dead father Anchises (grandfather of Filippo’s ancestor Anglus) and through him is shown a vision of his future descendants culminating in Augustus. Similarly, Dante descends into the Inferno with Virgil himself in place of the Sibyl, but instead takes a backwards glance at the post-mortem fate of history’s figures (especially Florentines, of course).

We meet the conflicted Petrarchan theme of terrestrial and heavenly love most clearly in Dante’s

Comedia at the ultimate liminal stage of entering Eden at the very end of the Purgatory, where Dante is first handed over to Statius as his next guide (and then ultimately Beatrice who appears on the chariot with the seven virtues). The references to the

Aeneid are overt here. When Dante, still with Virigil, first meets Statius, the latter Roman poet readily admits his debt to Dante’s current guide: 'The sparks that kindled the [poetic] fire in me ….I mean the

Aeneid (Purg. XXI 94-97). By the time of the final climatic parting with Virgil, Dante translates/quotes from Virgil’s own text, Aeneid 6.883:

Manibus, oh, date lilia plenis (Purg. 30.21), and again from Aeneid 4.23,

adgnosco veteris vestigia flammae, the last translated by Dante as

conosco i segni dell’antica fiamma” (line 48).

Although Dante is making no ethnogenic claims for himself, of course, the overt references to the

Aeneid in the

Comedia could easily be pressed into such service by the likes of Marziano. As pagan as the ethnogenic enterprise was, it is ultimately seen through the lens of

interpretatio christiana, and it is at this point in the

Comedia where Virgil is jettisoned for a purely Christian worldview.

Let’s also recall here that Filippo was portrayed below Adam and Eve, still in Eden, in the leaf of the Visconti Hours featuring his own portrait, therefore this entry into Eden at the end of the Purgatory had to have been of keen interest to Filippo. From Columbia University’s online Digital Dante commentary, this summary of that important section of the Comedia:

The last

canti of Purgatorio,

canti 28-33, take place in the garden of Eden, aka the earthly paradise. …An unusual feature of Purgatorio 28 to 33 is that these six

canti form a dense narrative block: “six cantos of carefully layered historical masques and personal dramas encompassing the supreme drama of the exchange of one beloved guide for another” [Virgil for Statius],

Purgatorio 28 is also a prelude to the micro-historical material of the earthly paradise: the intensely personal dramas of the arrival of Beatrice in Purgatorio 30 and the pilgrim’s personal confession in Purgatorio 31….The “

divina foresta spessa e viva” of Purgatorio 28.2 (in Mandelbaum’s beautiful rendition “that forest—dense, alive with green, divine”) is, obviously, the

in bono counterpart to the “dark wood” (“

selva oscura”) of of Inferno 1.2.....The pilgrim addresses

Matelda as the lyric poet addresses his lady, saying “

Deh, bella donna” (43); his love for her is figured in the three similes of

profane classical love that are rehearsed in the scene following their encounter:

she reminds him of Proserpina in the moment when she is ravished by Pluto and loses “spring,” i. e. the beautiful world in which she lived before her abduction (49-51; the word

primavera, with its Cavalcantian echoes, is here used for the first time in the poem); the splendor of her eyes (of which she gives him a “gift,” as the shepherdess gives a gift of her heart) is like that of

Venus’ eyes, in the moment that she falls in love with Adonis (64-66)….The first part of Purgatorio 28 is saturated with the language of love poetry, both vernacular Italian and Ovidian.

Matelda is many things, including the epitome of a love poet’s object of desire. It is as though Cavalcanti’s

pastorella (shepherdess) has come to life. Dante desires her, and his desire can no longer err.

Matelda is most of all an unfallen Eve, the unfallen version of one of the original inhabitants of this place.…. where Matelda explains that when the

classical poets of antiquity wrote of the Golden Age, they were perhaps dreaming of Eden.

https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante ... atorio-28/

What is not touched on above is the only appearance of

Aeolos in the

Comedia in this very section of Purgatory, which Marziano, in turn, has placed the wind god right before the appearance of the evergreen laurel-Daphne. Why? In regard to the primacy for the ethnocgenic project, Aeolos of course blows Aeneid off course (and eventually to Italy), courtesy Juno’s special relationship to the wind god. Marziano notes that Aeolos [

Eolo] is controlled by by the “spouse [

coniuge] of ethereal Jupiter”, thus even here providing the context of marriage (he could have just said Juno). But more to the point, while Aeolos doles out wintry blasts (hurting the fruits of Ceres and Bacchus) he also sends spring breezes – and what follows on that beneficial wind is an expository in accord with Dante’s description of Eden:

But when [Aeolous] summons the mild delightful Zephyr [perhaps most famous due to that wind’s connection and presence in Botticelli’s Primavera] the hillsides turn green instead of white, the woods are clothed with young leaves, all the fields laugh with grass, and new sweet streams flow from the sources; the glad world is now adorned with foliage and a variety of flowers, and the whole sky resounds, pleasant with the song of of flying creatures, and each living thing by nature inclines to love and coupling. (Caldwell, 81)

Marziano also comments that Aeolos is of the Aeolian islands off Sicily, the scene of the springtime capture of Persephone by Hades, although Dante merely likens Matelda to Persephone in the happiest of springtime terms (the reverse of descending into Hades is happening here – Dante is taking leave of Virgil for the

Paradiso).

Compare the above Aeolos passage above from Marziano with the appearance of Aeolos in Dante's Purgatory, where these very same springtime subjects are encountered in the Eden atop Purgatory: a mild breeze – specifically linked with Aeolos (Ëolo) – birds, leaves, grass streams, flowers and love, by turns chaste and carnal.

7 A steady gentle breeze

8 no stronger than the softest wind,

9 caressed and fanned my brow.

10 It made the trembling boughs

11 bend eagerly toward the shade

12 the holy mountain casts at dawn,

13 yet they were not so much bent down

14 that small birds in the highest branches

15 were not still practicing their every craft,

16 meeting the morning breeze

17 with songs of joy among the leaves,

18 which rustled such accompaniment to their rhymes

19 as builds from branch to branch

20 throughout the pine wood at the shore of Classe [Ravenna, where Dante spent part of his exile]

21

when Aeolus unleashes his Sirocco.

22 Already my slow steps had carried me

23 so deep into the ancient forest

24 I could not see where I had entered,

25 when I was stopped from going farther by a stream.

26 Its lapping waves were bending to the left

27 the grasses that sprang up along the bank.

28 All the streams that run the purest here on earth

29 would seem defiled beside that stream,

30 which reveals all that it contains,

31 even though it flows in darkness,

32 dark beneath perpetual shade

33 that never lets the sun or moon shine through.

34 Though my feet stopped, my eyes passed on

35 beyond the rivulet to contemplate

36 the great variety of blooming boughs,

37 and there appeared to me, as suddenly appears

38 a thing so marvelous

39 it drives away all other thoughts,

40

a lady, who went her way alone, singing [Matelda]

41 and picking flowers from among the blossoms

42 that were painted all along her way.

43 'Pray, fair lady, warming yourself in rays of love--

44 if I am to believe the features

45 that as a rule bear witness to the heart,'

46 I said to her, 'may it please you

47 to come closer to this stream,

48 near enough that I may hear what you are singing.

49 '

You make me remember where and what

50

Proserpina was, there when her mother

51 lost her and she lost the spring.'

52 As a lady turns in the dance

53 keeping her feet together on the ground,

54 and hardly puts one foot before the other,

55 on the red and yellow flowers

56 she turned in my direction,

57

lowering her modest eyes, as does a virgin,

58 and, attending to my plea, came closer

59 so that the sound of her sweet song

60 reached me together with its meaning.

61 As soon as she was where the grass is merely

62 moistened by the waters of the lovely stream,

63

she granted me the gift of raising up her eyes.

64

I do not think such radiant light blazed out

65

beneath the lids of Venus when her son by chance,

66

against his custom, pierced her with his arrow.

(Dante, Purg.XXVIII – translation from Hollander's Princeton’s Dante Project:

http://etcweb.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/dan ... 200&LANG=2 ).

Matelda recalls Dante's first passion for Beatrice (or Petrarch for Laura), placed in an Eden made green by Aeolus's springtime breeze, and also recalls the illuminations of Petrarch where Venus's son accompanies the beloved (Laura). Marziano has simply replaced Matelda for the more Petrarchan and resonant (for Filippo), Daphne. All in a context emotionally shot through with Dante's parting from the author of the Aeneid, Virgil, the penultimate source for the ethnogenic project of descent from Aeneas’s relations.

This material ties into my premise that Marziano specifically had Filippo’s marriage prospects in mind, preferably of a woman he could marry and bear successors from (alas, after executing his wife in 1418, Filippo pursued a woman married to one of his courtiers, Agnese del Maino, hence that issue being a bastard, Bianca). Since Petrarch was Filippo’s main literary love, naturally the chaste maiden chosen to be the symbol of Filippo's quarry is Daphne, seemingly paired with Cupido, who follows and completes the cycle of gods chosen for the card game. Aeolos appears as the blessings of springtime in Dante’s Eden - a sort of walled garden of love - and suitably comes immediately before Daphne (the laurel-tree, who would just as home in the green Eden as Matelda), a cognate for Virgl’s “golden bough” in the Aeneid but also the symbol of a suitable chaste maiden for Filippo. Why else is Daphne present?

If all of this seems too nuanced – too "literary" – Decembrio tells us this is precisely what Filippo was about, at least in regard to Petrarch and Dante.

Phaeded