Huck wrote:

For the case of Laura-Daphne and Ovid the "perverse Cupido" is a natural part of the story.

btw ... I think, that "Daphne" is just the Greek word for the Roman "Laura"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daphne_(plant)

Δάφνη (Daphne) as a name is transliterated in translation not translated. That is, in translations of Ovid, including Latin and Italian, the name remains Daphne, not Laure. If Boairdo had meant Ovid's Daphne, he would have wrote Daphne.

Laura as Daphne is a Petrarchian motif, one may identify her with the story of Daphne

as Petrarch did, drawing upont the word-play of Laura/Daphne = Laurel, but it is Petrarch's Laura that is being directly referred to, not Daphne.

However, Boiardo's verse here does not refer to Laura as Daphne, but to Laura as a personification of Reason, triumphing over the sensitive or bestial appetite (the perverse child Cupid). As a poetic theme one that is found in Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch rather than Ovid.

The description of Cupid as 'perverse' is a common one, along with other such descriptions as 'playful' or 'fickle'.

Perverse = deviating from what is considered right or good; wrong, improper, etc. or corrupt, wicked, etc.

Cupido = l'appetito sensitivo (the sensitive appetite), or what Thomas calls the appetito bestiale (bestial appetite), or the appetite that makes of one an ass (Boethius). As Dante says: "l'appetito sensitivo è contrario alla ragione", the sensitive appetite is contrary to reason. In that it acts contrary to reason then it is perverse (moving against what is right). Cupido is perverso in context of it acting contrary to reason (ragione).

-------------------------------------------------------

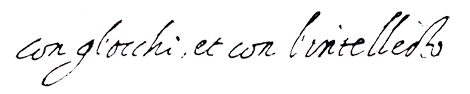

Ragion fe’ Laura del fanciul perverso

Cupìdo trionfar, ché mai non torse

Occhio da la virtù né il piè in traverso.

Reason made Laura triumphant

over the perverse child cupid, she never turned

her eyes from virtue, nor put a foot wrong.

--------------------------------------------------------

For An intermission

A litte shakespeare:

'Since thou art dead, lo, here I prophesy:

Sorrow on love hereafter shall attend:

It shall be waited on with jealousy,

Find sweet beginning, but unsavoury end,

Ne'er settled equally, but high or low,

That all love's pleasure shall not match his woe.

'It shall be fickle, false and full of fraud,

Bud and be blasted in a breathing-while;

The bottom poison, and the top o'erstraw'd

With sweets that shall the truest sight beguile:

The strongest body shall it make most weak,

Strike the wise dumb and teach the fool to speak.

'It shall be sparing and too full of riot,

Teaching decrepit age to tread the measures;

The staring ruffian shall it keep in quiet,

Pluck down the rich, enrich the poor with treasures;

It shall be raging-mad and silly-mild,

Make the young old, the old become a child.

'It shall suspect where is no cause of fear;

It shall not fear where it should most mistrust;

It shall be merciful and too severe,

And most deceiving when it seems most just;

Perverse it shall be where it shows most toward,

Put fear to valour, courage to the coward.

'It shall be cause of war and dire events,

And set dissension 'twixt the son and sire;

Subject and servile to all discontents,

As dry combustious matter is to fire:

Sith in his prime Death doth my love destroy,

They that love best their loves shall not enjoy.'

Venus and Adonis, Shakespeare.