Both this essay and his more recent one on John of Rheinfelden (translated at viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1095#p16830) are, as he suggests in the introduction to the one on John, reflections in the wake of his discovery published in The Playing Card vol. 44, no. 3, of clear evidence that playing cards were not only known in Florence of 1377 but played all over town. That essay does not have to be translated (although I hope to) to be appreciated: the results are in the English-language abstract, with the impressive details graphically displayed on the map that constitutes his Fig. 1, at the very end of the article (online at http://www.naibi.net/A/423-1377-Z.pdf). Here is the abstract:

How is that possible, given the absence of any evidence of their presence before then? How could the complicated art of card-making have reached such levels of production in so short time as to escape prior notice? (In fact some chronicles even say that cards were introduced only within the same year.) The same question can be asked about the variety of decks described by John, apparently in the same year, if that can be believed--the issue is not settled--who also says that playing cards were newly arrived there. So it is necessary to look toward the only other people in the area thought to have playing cards significantly before then, the Muslims. There, too, assumptions must be re-examined, presenting, as we shall see, new problems.Two books of the Podestà of Florence, with records from July to October 1377, have been examined for this study. In addition to the expected captures of gamblers playing the dice game of Zara - about one hundred- a dozen captures can be read there for players of Naibi, at such an early stage. All these players were Florence dwellers, living in six different parishes all around the town. The spread of the game in Florence is commented on, as well as the implicit confirmation that a remarkable production of playing cards was already established there.

On Islamic Cards

1. Introduction

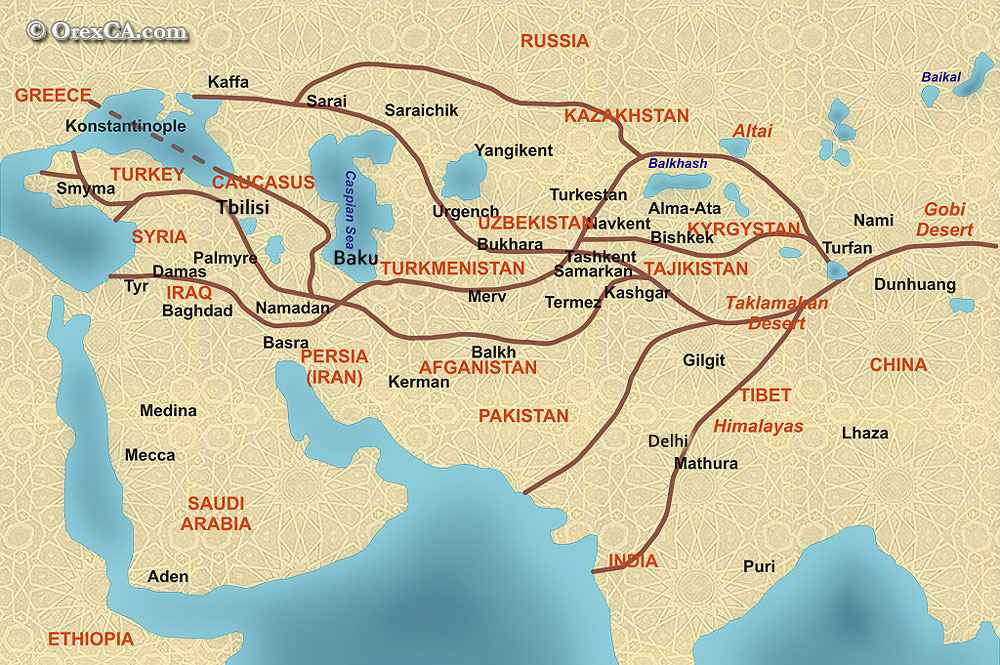

When historical research on the origin of the main popular games in Europe is pushed back to the time of the Middle Ages and further, our knowledge of Romance languages and literature, even Latin and Greek, is no longer enough: we must turn to the experts on Arab, Indian, and Chinese language and literature. The path most studied is that of chess, but card games have some similar aspects. These days historians are virtually unanimous in recognizing the place and time of the origin of playing cards as China before the Millennium; However, the path followed by cards from their regions of origin to Europe, probably more of a road, unfortunately has left few traces. Regarding India, whether the typical local playing cards there only spread from those already in Europe in the sixteenth century has been discussed at length (however, I am not aware of the latest research).

In Europe, however, the cards did not arrive from India, nor could they arrive directly from China. The most logical hypothesis credited by historians is that they arrived from the Islamic world, just as chess had arrived from the Islamic civilization a few centuries earlier. That, geographically speaking, it comes from the Far East to Europe through the Middle East cannot be a cause for surprise! There are countless products, even cultural products, that have diffused in the same direction; why not, like chess, also playing cards? However, a substantial and very significant difference is encountered: the game of chess is preserved in many Arab sources, from which we see that it was a game appreciated at the highest levels of culture and power and was imported to Europe as already a "game of kings"; there are still several obscure aspects of detail for the transmission of that game, but the basic lines are clear, at least as far as the transfer from the Islamic to the European-Western world.

Instead, for playing cards, the situation is quite different; the great Michael Dummett spoke of it at length in his principal

2

book 1 and even published a special study on the mamluk cards, the cards kept in Istanbul 2, which, since being described for the first time, have always represented a milestone for those seeking evidence of the spread of playing cards in the Islamic world. An extended, more recent discussion of the whole question by the same author can be read in his book in Italian 3. However we are surprised to find along with the mamluk cards only one card and a few fragments that would seem to go back to epochs preceding their introduction into Europe.

If I have not badly misunderstood, a reference to cards in the Islamic context must be understood in a singular way. Religious rules followed by the majority of Muslims prevented the card games they found from following the usual path from the Far East to Europe, which could not in this case find the usual intermediary in the Arab world. The reason why the cards were able to overcome this "barrier" has been associated with the Mamluks. One might say that in the westward diffusion, the cards arrived up to the regions around the Caspian Sea, where different populations, Turkish or similar, were allocated, which to the Arab world provided the Mamluks, highly sought slaves mainly because they were all very skilled riders. For their superior military capabilities, it happened that the Mamluk leaders who served under Islamic governments of other countries advanced in the army and government hierarchy until reaching the top, and even, in the particular case of Egypt, supplanting the Ayyubid dynasty, to its extinction. So the card games among them were not forbidden, or existed in less rigorous form, and could be noticed and copied by European observers.

To look for traces of card games among the Mamluks and in Islamic culture in general it becomes essential to deepen our historical knowledge. On games of chance in Islamic culture I happened recently to read a book that shows already in its title its interest in the issue in the question 4; precisely this book will be used as the basis for the reflections that follow.

_______

1. M. Dummett, The Game of Tarot, London 1980.

2. M Dummett, K Abu-Deeb, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, XXXVI (1973) 106-128.

3. M. Dummett, Il mondo e l’angelo. Naples 1993.

4. F. Rosenthal, Gambling in Islam. Leiden 1975.

3

2. The author and the book

Franz Rosenthal (1914-2003) was born into a wealthy Jewish family in Berlin and at university studied, in particular, various languages and ancient literatures. After graduating in Berlin in 1935, he taught at various locations, including initially a year in Florence. Shortly after, as a German Jew, he had to seek refuge from Nazism, emigrating and later finding teaching duties successively in Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States; during the Second World War he collaborated with the federal agencies with translations from Arabic and in 1943 obtained US citizenship. Returning to the academic environment after the war, he taught at Yale University as "Louis M. Rabinowitz Professor of Semitic languages" until 1967 and then as Sterling Professor Emeritus of Arabic until 1985, also in New Haven, Connecticut, where he remained until his death. President of the American Oriental Society, he wrote many works generally considered of great importance and originality analyzing critically many aspects of Islamic culture.

Since his book already indicated in the Introduction is the main source for this study, it will be appropriate to dedicate to it a few lines of illustration before getting to the information of specific interest. It is a beautiful edition, a book of 192 pages bound in whole canvas with titles stamped in gold, printed at Leiden (Fig. 1); the publisher. E. J. Brill, known for its numerous scholarly publications, appreciated internationally, as they are often among the best reference books, especially for oriental languages and related culture more generally. It is not hard to find information on this publisher, meanwhile become "royal" (Koninklijke Brill NV).

A book so serious and important, where is it to be found in Italy? Searching OPAC, we remain very disappointed: the only example recorded for all Italian libraries would be present in the Library of the Department of Oriental Studies of the University La Sapienza in Rome. However, in addition to recalling the academic level of the author, it is possible to present another fact in favor of the validity of the book in question: along with other works by Franz Rosenthal it was republished in 2014 by the same publisher in a new edition 5.

_______________

5. F. Rosenthal, D. Gutas, Man versus society in medieval Islam. 2 vols. Leiden 2014.

4

Figure 1 - The book used in the text.

It is to be hoped that the price of $246 for the work shown is valid for the two volumes, not only for the first; however, this book also is not easy to find in libraries, and even in bookstores, at least currently.

3. Specific reference and Eastern citations

Considering the rarity of the book mentioned above, it is useful to copy the entire section of interest in playing cards, before commenting on its contents; This is in the book described, on pages 62 and 63, just below the title “Playing cards”.

As we see, quotes related to playing cards in the Islamic world are very scarce for the period of interest, and totally unsatisfactory. As for me, also for the lack of specific appropriate knowledge, I will have to enlist the help of the imagination. If I were an expert in oriental literature, I would look in particular deeper into Persian literature: it seems impossible that the greatest contribution to the references collected by Rosenthal comes simply from a dictionary! If only from leafing through a common dictionary of the Persian language, different terms are encountered related to playing cards and their use, they cannot be something of very low diffusion.Due to the discoveries by L. A. Mayer and R. Ettinghausen of playing cards from Mamluk Egypt, it is now virtually certain that we have here the ancestors of the type of Western European playing cards most familiar to us. While for most of the cards a fifteenth-century date is assumed, R. Ettinghausen has

5

tentatively suggested that a card discovered by him is much earlier, possibly going back to late Fatimid times. We have no information how exactly those cards were used, but, as Ettinghausen has shown on the basis of information furnished by Laila Serageddin, we know that they were called kanjifah and that already in the early fifteenth century they were used for heavy gambling involving considerable sums of money.

The sixteenth-century Ibn Hajar al-Haytami mentions kanjifah in connection with at-tab wa-d-dukk. The Arabian Nights refers to it in the story of the learned slave girl Tawaddud between chess and nard, but while Tawaddud then goes on to elaborate on the latter two games, nothing more is said about kanjifah. The Persian dictionary lists ganjifah, ganjifah “pack of cards, game of cards,” ganji/ifah-baz “card player, trickster,” ganjifah-bazi “card trick, sleight of hand,” and ganjifah-saz “manufacturer of cards.” Long ago the suggestion was made by K. Himly that the Persian word was of Chinese origin.

A note signed by a certain Muhammad Sa’id which appears in the chess manuscript published by F. M. Pareja Casañas speaks of “the well-known paper game” (li.b al-kaghid) as an example of a game of pure luck. This may refer to playing cards. However, the writer of the note might possibly have lived as late as the eighteenth century, and his testimony is thus of very little use to us. [Translator's note: This transcription leaves out Rosenthal's footnotes. To read the text with footnotes, go to viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1096&p=16865#p16865.]

In regard to the derivation of the word from the Chinese, I could also check out the musings of Himly, who previously had appeared to me as a rather serious scholar of the history of chess. Some of his studies, scattered in journals more uncommon to us, were fortunately collected and republished as a bound book that I could read. The part that discusses the connection of ganjifah from Persian to Chinese, in his article of 1889, hypothesized that the corresponding Chinese name was Kan-Tsou-Phai, something like "card of Sun-Kan province". The correspondence appears anything but

6

convincing, but for a secure negative judgment it might better to have someone who was familiar with those languages and literatures. Of the same article by Himly, instead of reporting that discussion more extensively, I prefer to reproduce a brief parenthesis that would link our noun minchiate to the Persian meng, meaning lproceeding [procedimento], deception, game or player of dice, gaming house, with the possibility of finding a link between some of the associated words. 6

To give a negative assessment of this derivation, the advice of an expert does not seem to me necessary; it is nice to find for the name of the beautiful game of minchiate a less embarrassing connection than usual, but here it seems to me that we go beyond the reasonable.Wie ich es neben der frühen Verbreitung des Spieles durch die Mauren in Spanien sehr wohl für möglich halte, dass andere durch die Araber vermittelte Quellen nach Italien führen, möchte ich hier das alte Spiel der minchiate in Florenz erwähnen; wie nämlich das persische meng die verschiedenen Bedeutungen “Verfahren, Betrug, Würfelspiel, Würfelspieler, Spielhaus casa” und die Nebenbildung mengiya hat, so stehen dem genannten minchiate die Ausdrücke minchionare “zum Besten haben”, minchione u.s.w. zur Seite 6.

(As I consider it very possible that along with the early diffusion of the game by the Moors in Spain, that others mediated by Arab sources lead to Italy, I would like to mention here the old game of minchiate in Florence; namely, how the Persian meng with the various meanings "proceeding, fraud, craps, dice players, gaming house" and which has the secondary formation mengiya, stands in the so-called minchiate the expressions minchionare "to have the best", minchione etc. on that side 6.

Turning to "normal" cards, we could also think about the division between Shiites and Sunnis, today noted repeatedly in newspapers and on the news, as if [como se] the usual prohibition of card games were less stringent or absent among the Shiites. But to respond better, one should at least know the date of the dictionary and its references: if it is recent and the terms are of modern use, it does not serve our purpose of reconstructing the history of the second half of the fourteenth century. In short, it is plausible that the Persian dictionary entries have been introduced in later ages than those for which we are looking for evidence in the literature. In precisely the same way, it [this difficulty] is encountered, as explicitly indicated by Rosenthal himself, in the evidence that in his survey follows the Persian and ends the contribution.

Regardless of the origin of the name ganjifah, can it be concluded that cards were widespread in ancient Persia? For now we cannot find any reliable information before "our" year, around 1375. The secure pieces of information have two defects: the first is that,

_______

6 Karl Himly, Beiträge zur Geschichte des Schachspiels, Marburg 1984, p. 93.

7

being dated as early as the fifteenth century, it could be interpreted as limited not only to recent fashion, but also to that imported from Western Europe, in the direction opposite to that, certainly more convincing in principle, which remains to be documented better. The second is that it is evidence for the use of playing cards only in the aspect of chance and not that of possible "intelligent" games, such as to encourage their dissemination at a European level similar to that which occurred previously for chess.

4. References from Europe

After the inconclusive excursion into the lands of origin, we can look in Europe for useful documents on the arrival of playing cards. Then things get better clarity: there are in fact secure indications that the cards arrived there precisely from the Islamic world. We must address citations in "our" world, such as those of the Viterbo Chronicle, writing that naibi arrived in 1379 and had indeed a Saracen origin. For a discussion of this data I can once more refer to Dummett, who also commented on the notices of Moorish or Saracen cards in inventories at the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century.

The inventory made in 1408 of the property of Louis de Valois and his wife Valentina includes a "pack of Saracen cards" (Ung jeu de quartes Sarrasines); Valentina belonged to the Visconti family of Milan and married Louis in 1389. Similarly, several inventories compiled in Barcelona between 1414 and 1460 include "Moorish playing cards " (Jochs de naips moreschs) 7.

In short, despite the lack of evidence of their departure, we can affirmatively answer the question whether naibi arrived from the Islamic world, being content with a little information on their arrival. Some food for thought can also be inferred from the news of naibi decks in Rome, arriving by sea in 1428 in the same purchase containing hides 8. It may be useful to consider other properties and characteristics.

.

7 Ref. 3, p. 27.

8 http://trionfi.com/ev12

8

Good; in a manner convincing enough, even if when we search for a little precision, there are still doubts about where (especially if we are not convinced of a Cairo origin) and the like.

5. The name

Naibi, a term mking its appearance in the last quarter of the fourteenth century, cannot be traced back to one of the Romance or Neolatin languages; This finding already provides an important clue to convince us that it arrived on European shores of the Mediterranean from some foreign country. In principle, the term naibe alone, by whch the first playing cards in Europe were called, would be enough to allow us to ascend directly to the areas of origin, or at least the latest foreign transit zones in the long journey that began in China of the first millennium. Unfortunately, the term, unusual in European languages, is not common even in the Middle Eastern languages, or at least it does not appear that it was locally associated with playing cards.

The most accepted explanation for the origin of the term derives it from the upper cards of the deck, with pictures, or even writing, indicating the military leaders or naib, of Levantine armies; after having indicated only some of the most valuable cards, the word would be extended to indicate the entire deck and also the game in which it was used. Of naibi as playing cards we do not, however, find, a precedent in Arabic texts; also the study noted above confirms that the corresponding term was kanjifah. Usually, we know from the history of chess, these names varied in passing from one culture to another; not transmitted unaltered, including a lack in some languages of sounds and letters found in other, but a passage of the type chaturanga, shatranji, ajedrez is not found for playing cards. So we have to look for other indications or reflect on possible hypothetical reconstructions, without having the corresponding documentation.

6. The rules of play [Le regole di gioco]

Playing cards would not have been diffused so widely if they were not accompanied by some information, even if reduced to

9

a minimum, on the manner of using them for a game, which in turn evidently had to be pleasant. How could you use these objects? Today playing cards are used for countless games that are not only different from each other, but also belong to groups with different structures. Certainly at the beginning there was not the rich availability of today, but some game rules had to be necessarily associated with cards, as correspondent "software", from their first introduction onwards. In this regard we can think about what would happen in the case of a game in which virtually new software had set up everything needed for a sudden diffusions, at the same time fast and very wide.

Finding an example is not easy, but it can be imagined that instead of playing cards, the so-called “Chinese” morra had arrived in Europe and that, another very hypothetical but very necessary condition, it immediately gained favor with many European players. (Do not tell me that the game is too trivial for similar success; for this simple game there is even an international association! 9 What would be necessary in that case? Only the idea, just the fact that they were allowed three moves of the hand, to rock, scissors or paper (r, s, p), and that the rule is that the victory is determined by the circular sequence [r> s> p>]. That's all. Then it would have sufficed for a merchant, a pilgrim, a released prisoner, a visitor, anyone who had seen the game once, to be able to teach the game returning home, so that then from his knowledge and his practice it is spread like wildfire.

To meet with immediate fortune in almost all European regions, it is necessary to assume that with the cards came a particular game that immediately gained great popularity; everything leads us to assume that it was a trick-taking game, preferably also without trumps, probably to be identified with diritta, often mentioned in the oldest Florentine documents. The alternative hypothesis is not likely, that the cards arrived without corresponding "instructions for use" and that therefore in each location it was practiced in a different way, establishing very different traditions.

The greater historical problem is that for card games we have evidence that would be better compatible with a game like that of “Chinese morra”, which was taken as an example, while, even if the way in which the cards were

_____________

9 http://worldrps.com/

10

initially used in the game were reconstructed better, it would still remain to explain the simultaneous rapid spread of the associated "hardware" used.

7. The playing cards [Le carte da gioco]

To find in Europe a virtually explosive diffusion of playing cards around 1370 one would expect to find abundant traces in their native lands; they are not found. Of course, cards have always been perishable items and everywhere preserved only from some fortunate circumstance. But here it is seen that this is not just a lack of objects, it is also references to the game in the literature, to the terms themselves that indicated the cards and the games in which they were used; so even the hardware itself creates problems. How could playing cards have spread so quickly?

A logical hypothesis is that in the Islamic regions where they came from, they were produced in large quantities, so as to represent a new commodity of exchange between countries bordering the Mediterranean with the ability to export whole bales and crates to the various European countries; in short, an artifact that arrived there from distant countries together with the manner of use. This simple hypothesis, however, is hardly compatible with what we know about the countries of origin: the evidence is so scarce that it is explainable only by sporadic and limited productions, also in the same areas of origin. Some indication in this regard, however, we have met, reading of Saracen cards or finding naibi arriving by ship along with hides. Then all that remains is to assume that religious prohibitions related to the use of playing cards, but not to their manufacture for trade, especially if addressed to infidel markets. A little like, in centuries later, there existed gambling houses open for vacationers and guests of the thermal establishments, but not accessible to the inhabitants of the place.

In particular, it remains to understand if we have to look for a main transit channel, as we might imagine from active manufacturers in Egypt in the production of objects for export. In local histories it is found that Florentine merchants were in close relations not only and not so much with Egypt as with all the ports in the Mediterranean, beginning with the Spanish ones, with which the Islamic world had traditionally maintained privileged relations, also as intermediate steps for goods

11

coming from Africa, and not just from neighboring Morocco. The alternative is therefore an arrival in Florence of playing cards in large quantities mainly from Egypt or in correspondingly smaller quantities from many ports in Spain, Africa or the Middle East. Probably traffic along an exclusive channel would leave some trace in the books of accounts and memories of the merchants, and therefore it seems more logical to assume a secondary market, organized along with various other goods from multiple locations. The hypothesis is meant for Florence, where I know the relevant documents best, but could also apply to other large European cities that had rich trade with the Islamic regions.

On the other hand, it can also be supposed that precisely in Europe shops for the production of these new playing cards had to be implanted, and in such high numbers as to meet local requirements; as if mainly the software had come from Islamic regions, without a sufficient amount of hardware. In Florence the first notice comes in the summer of 1377, in which the games are commonly played on the streets! 10 With what cards? The local naibaio [card maker] craft could not exist before the arrival of naibi, unless one thinks of the production of pre-existing objects that were not too different. The profession involves various skills. The "normal” paper [carta] of cottonwool was quite rare and parchment a very refined product; let us suppose that they are found in sufficient quantities; several sheets of different kinds had to be glued together, and the surface, evenly covered with gypsum, also covered with a uniform layer of paint or gilding, and finally the symbols or figures on the playing cards had to be painted there.

Once learned, the craft could even give rise to a normal and quite generous production, also compatible with the appearance of various traveling card makers that produced in a city until exhausting local requests, moving immediately to a nearby town. Recurring testimonials - though for different times – show that card makers of this type also arrived from countries north of the Alps, probably favored by their traditional skills in woodworking, useful for preparing the early molds used to multiply the production of playing cards and sacred images. It is also true

________

10 http://www.naibi.net/A/423-1377-Z.pdf

12

that any of the Florentine workshops of painters could have included playing cards among the numerous minor art products simultaneously in the works, possibly with specialized apprentices or by subcontracting some intermediate work.

8. Conclusion

In the transmission of playing cards two related but essentially different aspects must be considered, that is, the relevant hardware and software, the cards and rules for using them. The card games are of many types and cover practically the entire range between a game of pure chance to those of particular reflection; in short, those of chance led to pure pastime; for neither extreme have we received significant evidence from the Islamic world, from which indeed playing cards arrived in Europe in the second half of the fourteenth century - while we have many notices of that origin for chess that also had arrived in Europe previously from the Islamic culture. No ancient Arab witness speaks of playing cards as a tool for intelligent games, suitable for personages of superior culture, and the testimonies that talk about it for gambling are very scarce and late (only the beginning of the fifteenth century).

In particular, a book by Franz Rosenthal, noted scholar of Islamic culture, has been taken into consideration here, and the discussion emphasizes the product aspect of the new gaming instrument. The absence of proper documentation cannot prevent the search for plausible reconstructions; in particular some possible paths for the introduction into Europe of playing cards and card games and their initial diffusion have been proposed and discussed, without being able to identify a single path that is more convincing than others. In particular, for the manufacture of playing cards used in Europe, there remains open the problem of distinguishing between local and imported products, in both cases trying to identify locations principally involved with production, trade and utilization.

Franco Pratesi – 08.02.2016