Hi, Ross,

Happy New Year!

Thanks for the posts -- a nice present for the holidays. Like Marco, I really wanted to comment earlier but, you know... holidays. Plus, once I got started rambling... well, you know about that too. So apologies for the delay, the length, and the rambling.

CELEBRATING 2014 WITH REAL TAROT HISTORY

As with

Howard's post, your posts are a great opportunity to reiterate, ruminate, and perhaps clarify

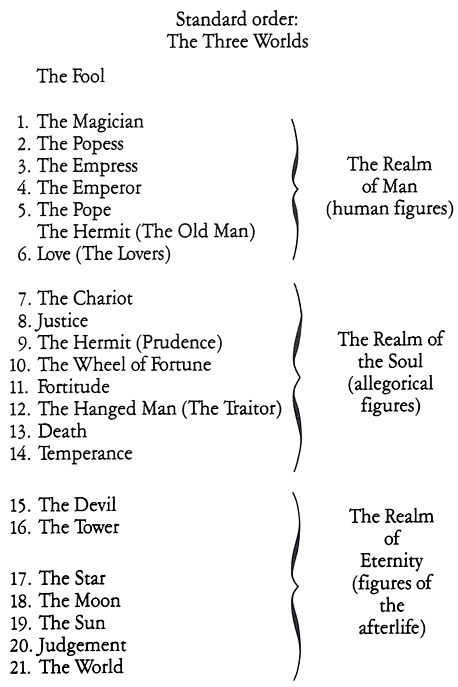

some of my favorite topics. In particular, this seems like a good time to emphasize the distinction between Dummett's findings and my own conclusions. Because attacking Dummett with strawman arguments is a long-standing Tarot tradition, I have tried to avoid giving people more opportunity for that. Because virtually no one agrees with my conclusions whereas his findings are factual, he should be defended against such conflation. A second big section is more to the point of your post. Yes, the Three Worlds schema (using John Shephard's term) is common, and recognizing that division in Tarot is the essential first step to understanding the cycle as a whole. However, you seem to be going a bit overboard with it, as if announcing the arrival of a new Universal Monomyth. It's a common structure, but not universal nor always well defined. So... basically, I'm just quibbling about emphasis and elaborating a bit. The main elaboration concerns Shephard's version of this and his terminology, as I have used them for a decade now. I'll talk about the Devil as one of the middle trumps in a separate post.

Most of the points to be commented upon are naturally disagreements, so it is helpful to keep in mind that we are, in most ways, substantially in agreement. Regarding Dummett's "three distinct segments" and Shephard's Three World model, (and my own 6/9/7 model), the discussion here is vastly more salient than most of what passes for Tarot history, here or elsewhere. I've spent many years attempting to get this topic front and center, with essentially zero success. I'll pick up on that below, but the point here is that significant questions are being debated. Dummett's findings (which were admittedly very limited, as discussed below) on the three sections and my own much broader conclusions about a 6/9/7 design to the trump cycle, are being considered (albeit mostly rejected) rather than universally ignored. Huzzah!

Regarding disagreements between you and I, these tend toward the trivial when taken in the context of 21st-century Tarot discussions generally. We're talking about historical Tarot rather than talking about Egyptian symbolism, Lombard pawnbrokers, alchemy, dowries, numerology, Albigensian heresies, Chess, or the Battle of Anghiari. For many years, both of us have taken the position that Tarot was, first and foremost, a card game. The content of the trumps had a two-fold purpose, as reasonably memorable and immediately recognizable tokens for cardplay, and as an inspirational subject matter to elevate the game. This is in keeping with other moralized games. Today, most people here would give grudging assent to that, before moving on to yet another revision of traditional occultist/New Age folklore or their most recent confection of historical fiction, weaving real Tarot history into a tapestry with famous people and events.

We have both attempted to construct a less fanciful, more historically sound reading of the trump cycle. Again, most folks here would claim to be doing sober analyses, both historically and iconographically, even though most of the discussions are laughably unrelated to Tarot or based on recycled esoteric folklore. Both of us are strongly inclined to respect the findings and consensus opinions that make up what you have called the Standard Model of Tarot history, dissenting only when there is a particularly strong and clear argument against some detail of it. When we do indulge in leaps of speculation, we are usually pretty clear about it and try to avoid building towers in the air, speculation based upon earlier speculation which is mistaken for factual foundation. Speculation one step beyond the facts, for the purpose of explaining those facts or answering another legitimate question, is very different than speculation which is two or three steps removed, piled up into a whole world of fantasy.

So, compared with the 99.9% of Tarot enthusiasts who do not share our common view of this material, we are substantially in agreement. For the half dozen or so (maybe a dozen?) who share that Standard Model view and commitment to less-speculative readings of the trumps, we are using the same approach but reaching different conclusions.

DUMMETT'S 3 SEGMENTS versus THE 6/9/7 MODEL

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:A depiction of heaven and earth will place heaven above earth; everyone intuitively understands this. The things of heaven are higher than the things of earth. So, in a vertical hierarchy, where would you then put depictions of

concepts and

ideas, or personifications of moral concepts like

allegories? Since they are not people you can meet or things you can bump into, nor are they real but untouchable like the heavenly bodies and supreme realities like God on his throne, such symbols will be placed higher than earth and Man but lower than heaven and God, in the

middle space between the two. This is what the tarot trump sequence does, and so do countless other works showing formally similar hierarchical orders. Only the specific iconographic content will differ, depending on the context and function of the work. This is the

threefold scheme of the trump sequence.

...we can say that the sequence of the remaining trumps falls into three distinct segments, an initial one, a middle one, and a final one, all variation occurring only within these different segments.

Game of Tarot, p. 398.

The threefold architecture of the trump sequence that Dummett discovered...

We need to clarify this, lest we libel the dead by attributing to him ideas he most certainly did not share and explicitly argued against. In a sense he found that design, stumbled across it, but failed to see it. Dummett drew attention to the two dividing points, but he did not suggest, much less argue for, three groups of trumps in a meaningful hierarchy. He was analyzing the various sequences for taxonomic purposes, to help understand the diaspora of early Tarot decks. That is, Dummett was doing exactly what Howard claimed he did

not do, using the different designs to understand the history of Tarot's spread. The variations in ordering are a bizarre fact of Tarot history, obviously at odds with the usual practice of conservative game play and requiring some explanation.

Michael Dummett wrote:If play is to be possible, the ranking of the trumps must be apparent to all players and subject to no dispute. How, then, are we to explain the variations that we find in the order of the trumps in Italy from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century?

(Page 396.)

Dummett then considers various arguments, not relevant here, and concludes that the variations reflect an extreme localization of Tarot game play. This is the passage which leads up to the quote above, and explains his interest in the analysis.

Michael Dummett wrote:The observable variations in the order must therefore be due, not to the absence of a fixed order, but to that phenomenon evident throughout the entire history of the game of Tarot: the extreme localisation of specific modes of play. Again and again we find that the players in one city or town play only amongst themselves and do not know those of a neighbouring town; the detailed rules, and sometimes the whole type of game played, diverge from locality to locality, the players in one circle being quite unaware of the manner of play of those in another, and, often, of their very existence. The different orders for the trumps that we find in Italy must represent different practices adopted in different cities, presumably at a stage earlier than that at which numerals came regularly to be inscribed on the trump cards. Evidently, quite a short time after the game of Tarot had first been invented, players in various cities or regions developed local peculiarities in their modes of play, which, in Italy, extended to the conventional order of the trumps; this must have happened before it became usual anywhere to inscribe numerals on the trump cards, and hence before the end of the fifteenth century. Modern players might feel that it would be impossible to memorise the order of twenty-one trump subjects so accurately as to be at once aware, without the need for reflection, which card was superior to which; but, as we know from the Bolognese game, this doubt is quite misplaced. The different orders of the trumps testify, not to a reliance on the numerals alone, but to the existence, at an early date, of wide local variation in the manner of play.

Note that this is an

observation of fact rather than an

explanation. Dummett does not offer an explanation for the deck and game being altered in almost every locale, other than a passing comment about the absence of indices. They developed "local peculiarities", in

every locale, for no apparent reason. Outside of Italy, this level of variation in decks did not happen.

Michael Dummett wrote:When we look closely at the various orders, we find that there was far from being total chaos. A first impression is of a good deal of regularity which, however, is hard to specify. Now the cards which wander most unrestrainedly within the sequence, from one ordering to another, are the three Virtues. If we remove these three cards, and consider the sequence formed by the remaining eighteen trump cards, it becomes very easy to state those features of their arrangement which remain constant in all the orderings. Ignoring the Virtues, we can say that the sequence of the remaining trumps falls into three distinct segments, an initial one, a middle one and a final one, all variation in order occurring only within these different segments.

Immediately after this analysis of the variations, he uses it as the basis for his further analysis of three regional traditions. This is the context of his division of the trump cycle into three segments. He was not doing iconography, at least not intentionally.

We also need to keep in mind that Dummett did not include the Fool, nor the three Moral Virtues, but only "the remaining eighteen trump cards". This is not a problem for him, as he was not attempting to explain the trump selection or arrangement. More importantly, he did not

explain his findings, not even in the FMR article.

Why are there these "three distinct segments"? This is a place where speculation, specifically about the design and intended meaning of the trump cycle, can be used to explain the facts. As usual, however, Dummett declines to speculate.

That is Dummett's version of a "threefold architecture". He did not deal with the lowest trumps as a group, at all, and his vague characterizations of the middle and highest trumps were essentially correct but largely unhelpful. No one -- not one person -- ever followed up on his findings and characterizations. (Excepting me, of course. BTW, if you know of anyone who pursued this analysis between 1980 and 2000, I would very much like to know about it, to be able to cite them on it.) Dummett's "three segments" analysis was not an iconographic explanation of the trump cycle, but a finding of facts which remained

in need of an iconographic explanation.

It was a couple decades after Dummett, when I learned about his analysis (indirectly, via a summary by Depaulis which Christian Joachim

Hartmann posted (June 11, 2000) to TarotL), that I pointed out that it was consistent with my own iconographic explanation of the meaningful design of Tarot. His analysis and my own both identified the dividing points of the Pope (and lower cards) and the Devil (and higher cards). My iconographic analysis explained his historical findings, while his historical findings were consistent with, and thus tended to support, my iconographic analysis. These groupings are another example of Ong's schematic relationships.

It has been pointed out that Dummett's second division, at Death, seems arbitrary in terms of the variations in ordering. That is, in terms of his stated methodology, Dummett's findings are even more limited than they initially seem. Because the highest trumps were in the same order, from the Devil through the Sun, in all decks, he could have chosen a different boundary. Dummett saw no design to the lowest trumps as a group and even excluded the Fool, while his methodology did not actually provide a dividing point for the highest trumps. Dummett had to take meaning into account, at least implicitly: Death is kind of a big deal, the end of this life and the beginning of the next. So he recognized that Death can reasonably go in either segment, as the end of one or the beginning of the next. Because he was just trying to do taxonomy, as prelude to understanding the early dispersion of Tarot, he could profitably ignore these "problems" -- they weren't

his problems. His analysis has essentially no explanatory power, and I cite him because his analysis does tend to support something which occultists and their contemporary apologists cannot conceive: divisions

other than 7/7/7.

Conversely, because I

was explaining the entire 22-card cycle of images, my analysis was into groups of 6/9/7. Although Dummett did seem to glimpse some of the iconographic significance in his FMR article, he offered no such interpretation. For better or worse, this explanation of the design of Tarot is entirely my own. Here's the point: although IMO his analysis is consistent with my own and tends to provide historical evidence and support for it, there is no reason to believe that he would have agreed, and therefore he should not be blamed for my views. Given the fact that virtually no one accepts my analysis (Marco and Hendley being the only two I can think of), exonerating Dummett seems important. I was so concerned about misrepresenting him that, before I first posted

The Riddle of Tarot online, I asked his friend and co-author John McLeod whether he thought that citing Dummett in this manner was misleading, or whether my presentation misrepresented Dummett's position. I also included this disclaimer in the first footnote:

Footnote A wrote:It should go without saying that although this presentation makes many references to Dummett’s analyses in The Game of Tarot, it seems unlikely that he would endorse such a (mis)use of his work. In quoting him at length, I do not intend to imply that he would agree with any of my own conclusions, any more than I agree with his suggestion that the images are a kind of sampler of triumphal images. He refers to Gertrude Moakley’s “brilliant suggestion” that the name trionfi derives from the subject matter of the trump cycle, but admits that it is difficult to discern what the underlying concept of the triumphal sequence might be. (GT 87.) Elsewhere, he writes that the designer selected “a number of subjects, most of them entirely familiar, that would naturally come to the mind of someone at a fifteenth-century Italian court”, and that “it is rather a random selection”. (GT 387.)

Moreover, most of my interpretation was developed before I even learned of his analysis of the early decks. I arrived at my interpretation based solely on the iconography and sequence of the cards as described and illustrated in Kaplan’s Encyclopedia. I have chosen to present my interpretation in the context of Dummett’s analyses because he has written the most comprehensive and reliable book on Tarot, which establishes many historical constraints for any study of early Tarot; he has framed the null hypothesis of a triumphal sampler and demonstrated its sufficiency for most historical purposes; he has pointed the way toward a study of sequential meaning, and done all the hard work of discovering and analyzing the early trump orders; and in my opinion, his findings support my conclusions... but that certainly doesn’t mean that he would agree.

At the same time, I wanted to credit him and use his finding to support my own analysis. One entire section of

The Riddle of Tarot is devoted to "Grouping within the Sequence", and it was written around his analysis. And there was this additional caveat:

Footnote C wrote:Although the present interpretation is quite different from any earlier attempt, both in its approach and its results, some aspects of it have precursors. Most notably, Michael Dummett analyzed the trumps into three groups, which are precisely the same as the groupings used here. The iconographic interpretation into three types of subject matter (the “Three Worlds motif”) is confirmed by the actions of fifteenth Italians who re-ordered the trumps, as shown by Dummett’s analysis: in each case, they maintained the division into three groups, reflecting three types of subject matter which they considered distinct and kept separate.

I have been promoting this as a

sine qua non first step in understanding the trump cycle for many years. The observation that there are three different types of subject matter answers a host of common questions such as, "if Tarot isn't heretical, then why does _______ trump the Pope?" (Merely displaying a

Triumph of Death image or

Dance of Death cycle also answers that question, but some people are just too fucking stupid to understand any kind of answer.) That is why I love to see others considering the Three Worlds model, in one way or another, rather than endlessly recycling

traditional occult and

New Age folklore or imposing topical irrelevancies (like

Lombard pawnbrokers or the Battle of Anghiari) on the trumps.

To this day there are very few who agree with me on the 6/9/7 analysis of the trump cycle into major sections. Marco and R.A. Hendley seem to be the only two who have repeatedly gone on record as saying this is a fundamental part of the design of the trump cycle, and presenting their own versions of it. Hendley, in a variety of brightly illustrated posts, has (largely) followed my own analysis and, on at least one occasion, cited my earlier posts. Marco seems to have a number of ideas very close to my own, as well as some differences. In particular, both have presented the same 6/9/7 division of the trumps into three sections, the macro analysis into three types of subject matter which I've been promoting since 2000. In my first detailed

presentation of the idea I described the three sections as 1) Religion Triumphs Over Society, 2) Virtue Triumphs Over Circumstance, and 3) God Triumphs Over Death and the Devil.

Looking back at some 2009 threads, you, Robert, and Kwaw (at least) preferred a 4-group system, 1/5/9/7. This is more in keeping with Dummett, who also left out the Fool, (and the three Virtues), and failed to categorize the trumps as any sort of unified whole. Now you have concluded that the Devil is not part of the highest section. As noted at the top, you are attempting something similar to what I have tried to do but as a less detailed interpretation rather than a card-by-card programme. Like Dummett, you don't seem to think such a specific explanation is appropriate -- the trump cycle wasn't that precisely structured.

Just to be very clear: IMO the two viable candidates for an Ur Tarot ordering are the Bolognese ordering (first column, GT 399) and the Tarot de Marseille ordering (fourth column, GT 401). You prefer the former, while I prefer the latter, but both are vastly more defensible than any of the dozen other orderings. Likewise, the two best interpretations of the trumps are yours, a somewhat more structured version of Dummett's triumphal sampler or vague hierarchy of common subjects, and mine, a well-defined and perfectly structured moral allegory. Moakley comes in third, perhaps tied with Paul Huson's 2004 discussion of medieval drama and the Four Last Things. So again, although I disagree with your conclusions, this is not in any way comparable to my "disagreements" with the occult apologists or New Age neo-Jungian simps.

SHEPHARD'S THREE WORLD'S MODEL

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:The threefold architecture of the trump sequence that Dummett discovered is not just a quirk of Tarot - it is a basic principle of spatial organization in iconographic vertical hierarchies - the basic moral valuation of hierarchical space, the low, middle, and high places; the center, and the sides....

Yes, but it seems as if you may have gotten a bit carried away in the presentation. This is reminiscent of Joseph Campbell's reification of his monomyth. It became something universal, which it could not be, and therefore the complexities and uniqueness of particular narratives had to be ignored or distorted so as to fit his Procrustean over-simplification. One size does not fit all, and there are crucial differences which tend to be ignored or falsified in the quest for universals.

Such generalities are good to note, useful conventions like many others. The real world and its art tend to be messy. Some works clearly display such organization, others don't.

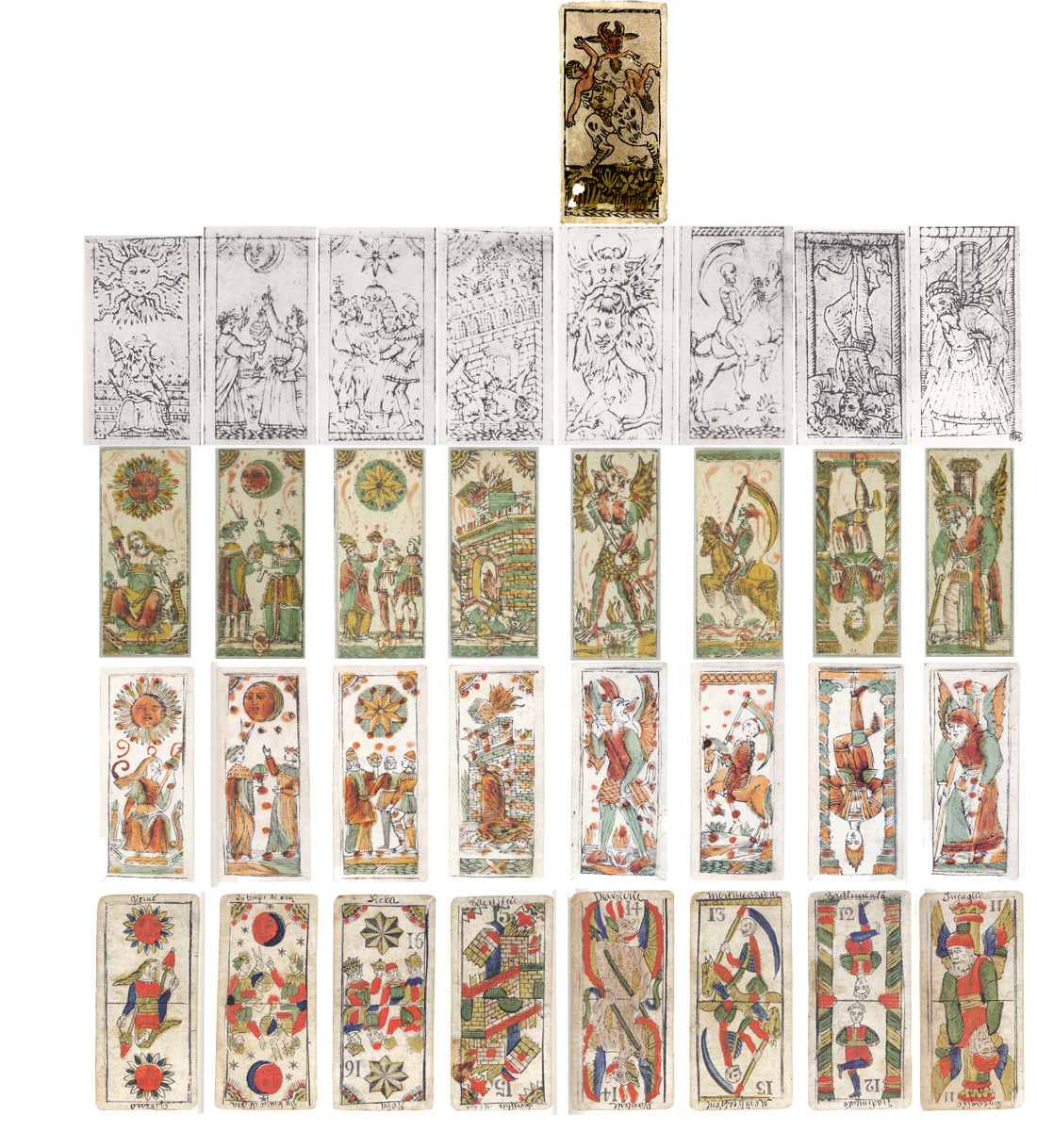

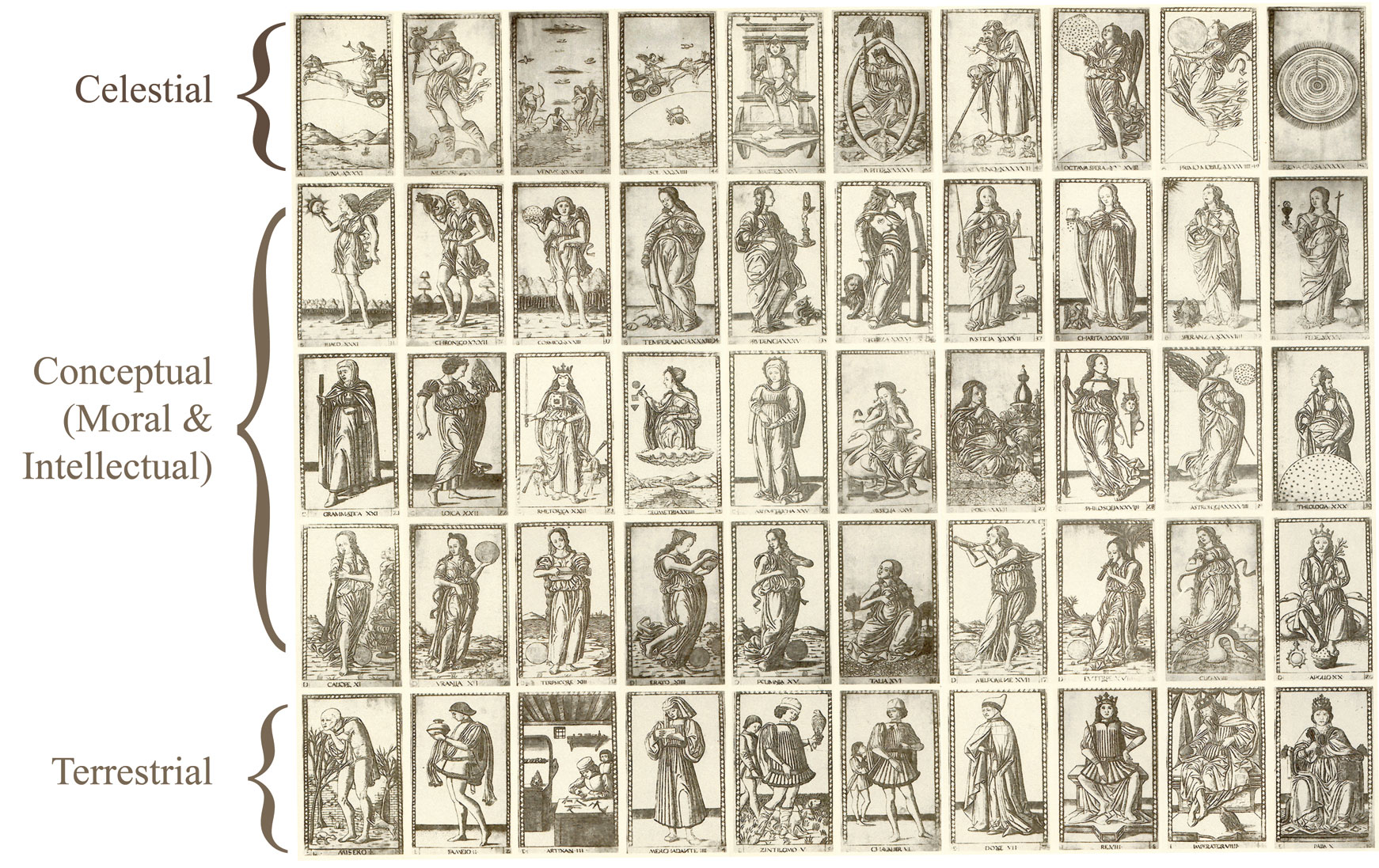

John Shephard's Three Worlds model (

The Tarot Trumps: Cosmos in Miniature, 1985) is very closely related to your construct. He uses it to describe the same aspect of the trump cycle, and like you he also emphasizes the parallels with the E-Series prints. He introduced it, appropriately enough considering his theories, via the cosmological spheres of that cycle. The four sub-lunar spheres, lowest in the Aristotelian cosmology, he termed the

Realm of Man. One of those, the sphere of Fire, he also called "a middle term, a middle world in the chain of being between the aethereal world of Heaven and the mundane world of Earth". (Clearly, the cosmological parallel is being abused here -- it just didn't fit as he wanted it to.) In art, specifically the E-Series, this middle section "consists of figures all of which are allegorical. It deals with the spirit in man, the soul from its entrance into the human body", and he calls it the

Realm of the Soul. The highest level "consists of figures of a theological or celestial nature. It shows the life beyond Death, with the Devil and Tower representing the fate of the imprudent soul consigned to Hell, while Judgement and The World show the Resurrection and the proper reward in Heaven for the virtuous. It corresponds broadly to set A of the Mantegna series, the Heavens. I call this set the

Realm of Eternity." Despite a lot of confusion and occultist preconceptions, Shephard came close to getting this part of his structural analysis correct.

Shephard, blinded by traditional numerological preconceptions, excludes the allegory of Love from the rest of the allegorical figures, and wants to rename Time/Hermit as Prudence, an allegorical figure, but also to rearrange the sequence to exclude him from his proper place with the other allegorical figures. He wants very much to force the trumps into septenary groupings, as had generations of occultists before him. Still, he came closer to sorting out the macro structure of Tarot than anyone else, and his Three Worlds terminology and descriptions are excellent. Like Dummett, he advanced the discussion a bit -- we should look for and acknowledge such progress. Also like Dummett, no one attempted to advance Shephard's analysis further, although endless variations on the occultist septenary analysis continue to this day. We are not the first to look at this stuff, and both these guys from the 1980s should be remembered by those who are now discussing this topic, three decades later.

Here is a 2001 TarotL post which makes the same point about three realms or worlds, each with a different type of subject matter, connecting it with Dummett/Depaulis and once again using the E-Series prints as the primary cognate example.

The Virtues of Tarot de Marseille (March 29, 2001)

http://groups.yahoo.com/neo/groups/Taro ... sages/9532

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Court cards not numbered; rank is implied. Similarly the court cards don't tell a story, although they are a meaningful hierarchy. Similarly for Chess figures or any game with symbolic figures representing the hierarchy.

Good point -- another schematic grouping with hierarchy. Pips were not exactly numbered either. That is, they did not have numerical indices, (contrary to some things one might read on this list, from those who have not read Dummett). Their rank was illustrated by picturing a number of items. Other things were significantly grouped, as well. The card player knew that in the round/female suits the greater the number of items depicted, the lower the rank, while in the linear/male suits the larger the number of items the greater the rank. Just as pawns are of a different kind than the second row of chess men, so pip cards are different than court cards. These are more examples of Ong's schematic groupings which are generally recognized without comment.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:"It would be absurd to suggest that the order of the court cards was invented to teach how a court was organized. It would be absurd to suggest that the Chess pieces teach how a kingdom is organized. Both can do that, in a vague way, but that it not their intention. The understanding of the hierarchy is implicit, expected of the audience. Similarly, all Italians of the 15th century would recognize the vague hierarchy in the trumps: celestial and eternal things are higher than moral allegories, and moral allegories are higher than human stations/types. These are the three divisions recognized by Dummett, and already recognized in the 19th century (and arguably the 16th).

"The nature of the differences among the various trump orders shows that there was a broad understanding of these three divisions, and the overall hierarchy."

We should tread gently on the "recognized by Dummett" part, even though I've put it in similar terms in the past. As noted above, he did not appear to recognize the overall design toward which he had pointed. "The question is whether the sequence as a sequence has any special symbolic meaning. I am inclined to think that it did not." When I am just a lone voice in the wilderness, I tend to take polemical and even hyperbolic positions, but if there are others with a similar view, it becomes more important to state things a little more precisely. In general, however, that's always been my position with regard to Dummett's findings.

Riddle of Tarot wrote:The iconographic interpretation into three types of subject matter (the “Three Worlds motif”) is confirmed by the actions of fifteenth Italians who re-ordered the trumps, as shown by Dummett’s analysis: in each case, they maintained the division into three groups, reflecting three types of subject matter which they considered distinct and kept separate.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:"Threefold scheme of art; planets (children), Schifanoia, pictures of people having visions, etc. Pseudo-Mantegna perhaps most relevant scheme:

1. Ranks

______ __Muses (poetry, art)

2. Ideas --- Liberal Arts (science, intellect) _________Virtues (morality)

3. Celestial

Yes, the 3-part analysis is one of the most basic. More basic still is the 2-part division into this world and the next. Representatives of Mankind and conventional personifications need not be distinguished; Everyman is himself an allegorical personification. Likewise Emperor and Pope, when they represent all secular and clerical people. All the changeable sub-lunar parts of the cosmos, or the circumstances of this life, including representatives of Mankind constitute the lower, mundane world, while the rest of the cosmos and judgment by God are of the higher, divine world. In a cosmograph, the Moon is the obvious dividing point, given that it is changeable like the sub-lunar world even though it is part of the eternal/celestial realm. In a

vita humana with personifications, Death is the obvious dividing point, leaving one world and entering the next. The distinction between the Realm of Man and the Realm of the Soul, while appropriate to some works, is routinely ignored. The most prominent example is the

Dance of Death where the Ranks of Man is completely joined with the personification(s) of Death.

If present, the lowest level may be illustrated in various ways. Not only are most Ranks of Man motifs unique, but there are other forms this level may take. Essentially, Shephard's Realm of Man depicts some representation of Mankind or Everyman. For example, the lowest section may show Adam in some form. Etymologically and in many contexts, Adam=Mankind, and his sin condemned all. Showing the Creation or, more commonly, the Fall of Man via Adam and Eve, indicates that the overall story is about Mankind and specifically post-lapsarian Man. Rather than a ranks or stations/estates motif, Mankind as a whole may also be indicated by showing representative ages. This shows Mankind and also his life cycle, just as a Ranks shows Mankind and his various places in society. Both are sketchy, schematic abstractions which employ something like synecdoche, representing the whole via characteristic parts. The two most extreme versions of that are showing just one figure, Everyman, and showing just two figures, lowest and highest, in the figure of speech called merism. Most often, women are implied rather than being explicitly depicted but, again, things vary and are sometimes quite messy.

The middle group may also take various forms. Commonly, a grouping of Deadly Sins could be used to symbolize the things of this life. We suck, hence the need for Grace. The opposite, Virtues, could be used just as well, as could a combined Vice/Virtue schema. The four Passions of the Soul is another schematic motif to illustrate

vita humanae, as is their subjugation via a Stoic

apathea or Christian transcendence, mystical triumph in this life. These and many others are allegorical versions of the circumstances of life. In every case, a selection is made from the countless possible choices.

The subject matter of the E-Series obviously is quite different than the subject matter in Tarot. In addition to being commonplace subjects needed by artists in their compositions, (the actual historical function of the project), the Muses, Arts, and Virtues are an aspirational catalog of strengths. To have inspiration, skill, and virtue is to be great in this world and prepared for the next. The prominence given to the Pope, Apollo (a "type" of Christ), Theology, and the three Pauline Virtues, emphasize this humanistic duality. This can be the middle register of a three-level work just as can the Seven Deadly Sins. One design is hopeful and encouraging while the other is a dire warning. Neither is like an Ages of Man design, an actual

vita humana, or like the

contemptu mundi cycle of the middle trumps, which schematically illustrates the vicissitudes of Fortune and the role of Virtue in the life of Man. Even within Tarot the design varies. In the Bolognese sequence, Virtue is shown with the Triumphs, as something desired but which cannot prevent reversal and downfall. In the Tarot de Marseille sequence, each of the three Moral Virtues is shown triumphing over one of the three turns of the Wheel.

Likewise, a third section is transcendent, something beyond this life, but it may still take various forms. This may reflect an individual judgment (as in Costa's allegory in Bentivoglio Chapel), the Last Judgment as in countless works, or something as vaguely allusive as the cosmograph of the E-Series. It could be a mystical transcendence in this life rather than post mortem, again failing to conform to a neat, distinct Three Worlds design.

In various ways, the elements may be combined rather than separated into groups. For example, in Petrarch's

Trionfi there is often no clear-cut, simplistic analysis. Fame is of this world, yet triumphs over Death. Time is usually what leads to Death, yet Petrarch used it to wash away Fame, an

ubi sunt trope. Time and Fame are conventional allegories, very popular circumstances of life, and yet in the

Trionfi they appear after Death. Messy. As another example, in illustrations for Petrarch's cycle there is sometimes mixing and repetition. The Triumph of Death, in particular, is the third of six in the cycle but often contains an explicit Ranks of Man, (with the characteristic emperor and pope), the allegory of Death itself, (always the most significant point in Man's life), and representations of both Heaven and Hell, or souls being carried by angels and demons. One might expect the Ranks of Man to appear in the first Triumph, and often it does. Again, art is messy and often less schematic than things like the E-Series.

So yes, different categories of subject matter are being illustrated, and that the simplest, most clear-cut diagrammatic version of this may be loosely characterized as mankind, allegories of life, and things which transcend this life. But we should keep in mind that this is a gross simplification which is not always directly applicable. It is the context which makes a detailed explanation of the trump cycle possible, but it has little explanatory power in its own right.

I would argue that the most generic description of this 3-part design, at least in the Western European tradition, is "Triumph of Death". Death is the one thing that unites all Mankind and which occupies the same position in all human life -- its end. Death is the great transition between the two realms, and while it ends this life it begins the next. Death is the greatest theme of Christian allegorical art, with endless works of

vanitas, memento mori, ubi sunt, and related genre. From

Vado Mori and the

Three Living and Three Dead through the pervasive

Dance of Death and

Triumph of Death per se, with many unique allegorical works like Petrarch's

Triumphs or Michault's

Dance of the Blind.

This is partly because death is that natural end of Everyman, but also because death is at the heart of Christian mythology. In Genesis, Adam/Man sins and his punishment is death. In the Gospels, Christ's death is the sacrifice to atone for Adam's sin, and his own resurrection, triumph over death, is the first fruits of the general resurrection. In Revelation 20, we have the final triumph over the Devil/Sin and death. Tarot is another in this vast tradition of Christian allegories of death. The trump cycle is itself an elaborated

Triumph of Death, elaborated in terms of the middle trumps which show the life cycle leading up to death.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Looking for any authority who described "threefoldness" in vertical hierarchies proved difficult; it became apparent that it was such a fundamental, underlying and completely natural basis for the spatial organization of iconographic information, that people describing such art assumed it rather than explained it as a principle.

First, thanks for the pointer to Ong's 1959 article, "From Allegory to Diagram". He may not have given you the quote you were hoping for, but Ong's discussion of the "schematic relationships" among the figures, the diagrammatic composition, is directly on point for Tarot. This is the structural aspect, what I've called the sequential context, which constrains and clarifies the intended meaning of the trumps. This is what the three sections mean for Tarot: they are the macro structure of the trump cycle. The micro structure consists of the smaller groups, the eight duos and two trios that I've called affine groups. The arrangement of these three major groups and ten lesser groups tells us what the trump cycle was intended to convey, the

intentio operis. Ong was making the generic point, and Tarot -- properly understood in terms of those groupings -- is just one more example illustrating his point. These structures are what enable us to dismiss most orderings and interpretations and get closer to the intended meaning.

Your attempt to find the best analysis of this schematic tendency in a general sense is interesting. Finding a good quote, or creating an pithy and insightful description yourself, seems worthwhile. As noted above, this is an over-simplification like Campbell's 3-part cycle. His Separation, Initiation, and Return can even be stretched to cover the Three World analysis I've offered for Tarot, the three realms you are discussing here, if one is so inclined. Our individual identities as suggested by a Ranks of Man can be taken as our embodiment in this life, this world, separated from the Divine by Adam's Fall. This life is naturally our initiation into the next, and the De Casibus or Wheel of Fortune cycle both initiates us and leads to death. Death returns us to God for our Last Judgment.

The question is to what extent this sort of simplification is helpful. If you say, "Campbell's Monomyth" to a Tarot enthusiast, you fall immediately into a swamp of vacuous impositions and empty analogies, taking you

away from an historical analysis of the specifics of a particular Tarot deck or decks.

You used the term prolegomena, preliminary remarks for the study of the groups, subjects, and sequence of the Tarot trumps. That is precisely how I used such a discussion in various presentations, most notably in

The Riddle of Tarot. Although the emphasis was on analysis of the various trump cycles themselves, rather than other works, numerous examples were cited of composite works uniting different types of subject matter. Over the years many more have been presented, and I have even used this tripartite analysis to define Triumph of Death in a general sense. As such a basic conceptual aspect, it needs to be presented (i.e., it is absolutely necessary, which is why I continue to return to the subject) but it explains

very little about the trump cycle details.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Triumphal Arch of Alfonso V in Castel Nuovo, Naples

1. Triumph of Alfonso (terrestrial)

2. Virtues (moral)

3. Archangel Michael flanked by saints Anthony and Sebastian (celestial)

Nice example.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Lorenzo Costa, Cappella Bentivoglio Triumph of Death (starts with allegory, introduces concept of "literal" as a subset of "terrestrial" or "real" (actually vice-versa))

1. Triumphs of Fame (and Fortune) and Death (and Chastity)

2. Exempla (Fame), souls ascending (Death)

3. Souls ascending, angels, God the Father, Jesus, Mary (in Death triumph only; the two compositions are a diptych)

Here we see some problems that often arise when attempting to force-fit a particular work into a "universal" schema. The truth of the work is that it's just messy. Contemporaneous figures are used in the allegory along with historical/legendary ones, which is to say that it does not fit the oversimplified model. I won't go into your elaborate speculation (in which you suggest that there may be a specific topical reading to virtually every detail) except to say that, in the absence of documentary support, you may be reading too much into it.

Regarding the messiness, it is worth noting that the composition's diagrammatic flow begins with scenes of the Fall of Man from Genesis. These are in the center of the upper-left quadrant. Surrounding them, Mankind's fallen state is exemplified by eight legendary incidents, exemplars arranged in a Wheel of Fortune. Historical stories turned into a Wheel of Fortune, with the Fall of Man at the center -- where Time or Fortuna would ordinarily be placed, turning the Wheel. It is unique, and conceptually messy. As a grouping, these historical images are far removed in time from the topical elements in the lower parts of the paintings. They are also different in kind from the allegorical elements in the lower part of the panels, and from the soul rising to judgment in the upper-right quadrant. So on the one hand it is both unique and seemingly messy, at least if one wishes to oversimplify.

On the other hand, the pieces are neatly illustrative in their own right and they are united in the overall composition to tell a coherent story: starting with the Fall of Man, then ancient examples of Fortune, contemporaneous examples of Fame and Death, and finally the triumph over death. It fails miserably to conform to either neat groupings of like character or to the simplistic bottom-to-top reading. Spatially, the narrative thread begins at the top, goes down, sideways, then up. As such, it serves as a great warning about the one-size-fits-all, monomyth approach to iconography.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Tarot trump sequence

1. Human types (highest and lowest; highest complete ranking of court cards)

2. Virtù and Fato

3. Heavenly order

[...]

The tarot trumps are neither monument, nor painting, nor quasi-encyclopedic model-book; they are the pieces of a game. Their context is ludic, and play-function is therefore one of the constraints upon their design.

It's good to recognize, and never forget, that Tarot was a game and the trump cycle was intended as both a moral allegory, to make the game inspirational, and as an easily learned and readily usable hierarchy of trumps. Beyond that, however, looking at the moral allegory itself, there seems to be little about the game which would constrain either the selection or arrangement of the subjects -- they just need to make some sense, which is generally true in other contexts as well. It is a cycle which could be easily adapted for a chapel or other architectural space, like other unique cycles we've seen, or to a series of prints.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:This explains why the various sequences share the threefold sensibility, and why Dummett was able to reduce it to three families. It also explains why the designer chose these three types of subject matter, vertically arranged in three divisions, to illustrate the pieces of his game.

I'm not sure what you mean here. It seems as if you are saying that the

commonplace division into three types of subject matter in various works of art explains the

specific division into three types of subject matter in Tarot. If so, then it seems simpler to just note that complex works of art, grouping and/or mixing different types of subject matter into a unified composition, were commonplace. If it is stated that way, then perhaps the absence of a more detailed analysis in the iconography literature is not surprising.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It finally explains why it was easy for the players to understand the logic of the subjects, why they were where they were. The threefold structure is a necessary, but not sufficient, explanation for the choice of subjects and their number - different subjects could occupy the lower, middle and highest levels...

Yes, the three types of subject matter are necessary to understand the logic of the design of Tarot, the

arrangement of the subjects into groups in archetypal decks. But a different design could easily have been chosen. If you want to keep roughly the same number of trumps, one can take the middle three decades of the E-Series, keep the Muses (9), the Liberal Arts (7), and the Virtues (7) -- voila! Twenty-three trumps in three clearly defined groups but lacking the Three Worlds structure. If the orderings of each group were taken from literary sources, it might seem to be very didactic and mnemonic set of trumps. Even in terms of Tarot, however, the Three Worlds aspect does not seem to help at all in understanding the

choice of subjects or their

number. These seem to have been based on other considerations, specifically, a detailed iconographic program.

Well, that was more fun -- thanks again. I started on a reply to the Devil posts... maybe tomorrow.

Best regards,

Michael

We are either dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants, or we are just dwarfs.