Marco wrote,

mikeh wrote:So we have, assuming the relationship to the whole is 50%

Bagat: relationship to whole.....40% (i.e. 80% similar, conservative)

3 out of 8 components (giving each 2 pts) of individual image:.. 19% (Hermes, offering something he thinks important; but not clear-cut what it is, not old, stick different function)

Total 49%

Hello Mike,

it seems we basically agree on the fact that the Genius has little to do with the Bagat: we don't even get to a 50% similarity. It is visually completely different and it only has a similar position in a sequence which is a vague parallel to the trump sequence. BTW, is the 80% similarity with the respect to the whole based on the identification of a Fool in the Tabula?

We could just as well say that the Bagat is John the Evangelist, since John appears at the beginning of the Book of Revelation which also has analogies with the trump sequence. Actually, Duerer's John also has something like a desk in front of him, for his ink.

We can match anything with almost anything else with a 49% degree of success.

It is surprising to me that you cannot see the visual similarity between the Popess and Giotto's Fides, but I can only acknowledge your point of view: perception is always subjective.

On my rating scale, I would interpret 49% as a significant amount of similarity.

I was not basing my estimate on there being a Fool. There is no Fool in the image, just in the text, and even then applying to many people, not just one who represents the type. The corresponding figures in the image have no Fool attributes. On the other hand, they are fools, and that is important to the allegory, so I guess in that sense I should count them, rather weakly. as standing for the Fool. Now I wonder if there might be an ironic allusion between them, crowding around winged Fortuna, and the people crowding around Fama in the Fama depictions on birth-trays, cassoni,etc.

In my comparisons, I forgot about the lack of a table, which counts against the Bagat in the imagery category. I also forgot about the lack of the Papessa's knots, in the imagery part on that side. I don't know if the two are comparable. If so, the two omissions cancel each other out. If not, then one gets more points. It's mainly that part that is subjective, the quantification and how to interpret it, e.g. what is "significant" vs. "little".

I do see the resemblance between Fides and the PMB Popess. I have pointed it out myself on occasion, in the same breath in which I point out the relationship of Inconstancy to the Tower card, Despair to the Hanged Man, and Prudence to the Bagat (young man at a table). These are more or less visual similarities with more or less conceptual similarities. There is much commonality between Giotto's images and the PMB. In fact, I think that most or all of the cards by the first-artist PMB that cannot be presumed to have been in the Cary-Yale owe something to the Giotto series (see

viewtopic.php?f=12&t=848, first post), and some in the Cary-Yale and PMB second-artist as well.

About John the Evangelist, let me repeat that I am talking about allusions, not identification. It is possible to see allusions that aren't there, to be sure; we know they're not there if there is evidence in the text that contradicts the interpretation, or the life-situation of the writer or reader, what he could have read. That's why I situate the comparison very much in time. We know that the Book of Revelation does not make any allusions to the Bagat because the Book of Revelation was written much earlier. Whether the Bagat in 1523 alludes to the author of the Book of Revelation is another matter. That's a matter of comparing the two series, related images and writings available at that time, and the context of artist and viewer/reader. Generally the author of a book is not part of the allegory, even if some artist does put him in an illustration. Someone would have to analyze the objects on the table and in his hands in terms of their contribution to the allegory in Revelation, as carried out in the sequence and in the text, as well as his demeanor, age, dress, etc. in the same context and the conventions of the type of allegory that is being considered, i.e. Christian vs. Hermetic, etc. Also competing allusions would have to be weighed within the same framework, i.e. whether the Bagat might more profitably be compared to the Alpha who is also Omega, i.e. the first and last card in the sequence.

Those were the kinds of considerations I offered in my lengthy posts on the frontispieces and on the Bagatto himself in the sequence. It takes a lot of work, and simplicity, I think, is not a criterion. What is simplest is to say that there are no allusions to anything ever. There are also good arguments vs. bad arguments. Bad arguments are ones that are very forced, making much out of very little. I am not at all sure I can say anything more precise; I at least hope I know the difference when I see it (I've been re-reading

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and its discussion of "quality"). That's one of the things that really fascinates me about Decker's book. I approve of his perspective, I like some of his conclusions, and I think many of his arguments for them are in my view bad. What is the difference between "bad" and "not consistent with mine"? I would hope to get some perspective from discussion here. In my post on Chapter 4 of his book. over on the Unicorn Terrace, I will give examples of what I consider both bad and good arguments for Egyptianization in the historical tarot.

I thought of another argument that the Bagat is being alluded to in the images of the old man in the Cebetis (a position I share with Decker) and the dice-thrower in the Fanti (a position I share with Place). In Alciato's 1544 list of titles, in the C order, he gives "Innkeeper" (caupo) as the title in the Bagat position. It is also the name in Piscina's Discourse. I had always thought that this was just based on thinking that the table was a desk, the wand a quill, the cup a tankard, etc. However the innkeeper as metaphor applies to the old man in the Cebetis frontispiece; he is at the front, letting people into the establishment, even giving them a brochure on the amenities and what to do if problems arise. Life is an inn with many rooms, temptations, stairways, basements, and people. In that case, the allusion in the Cebetis frontispiece is not so subtle: it is to the Innkeeper in the tarot.

On this Piscina says--and I think I have to give the Bagato a big lead-in here (

http://www.tarotpedia.com/wiki/Piscina_Discorso_2):

...tutti gl' huomini di qualunque sorte si voglia, accadendogli d' ir in viaggio solevano allogiar prima alla hosteria dello Specchio ma da molto tempo in qua andarsene tutti più voluntieri a quella dil Matto, si come più convenevole, al volere, & alle attioni loro, e per ciò non senza grandissimo mistero vegiamo il Pazzo nel giuoco de Tarocchi esser dipinto a modo che sguardi indietro ad uno specchio beffandosi della fama dello [9] Specchio perduta appresso tutti gl' huomini, ì quali solevano concorrere all' hostaria soa, e perciò in faccia molto gioiosa si rallegra anzi si glorià del credito ch' egli hà, si che tutti gli houmini gli corrono dietro, e lo segue colui che s' addomanda il Bagato in habito di hoste, non senza accorto avedimento, percioche si come le Insegne delle Hostarie sono più presto da Forastieri vedutte che cercano d' allogiare che gl' istessi hosti, & che etiamdio l' insegne sogliano dar buon credito all' hostarie come veggiamo, in quelle de Gigli, Aquile, Falconi, Corone e Re, le quali in tutte le buone e famose Città demonstrano buon alloggiamento, così il Matto è stato anteposto come figura dell' hosteria al Bagato che è l' Hoste, per signficar ella esser quella famosa Hosteria nella qual la magior parte de gli huomini sogliano andar ad alloggiare.

And the published translation:

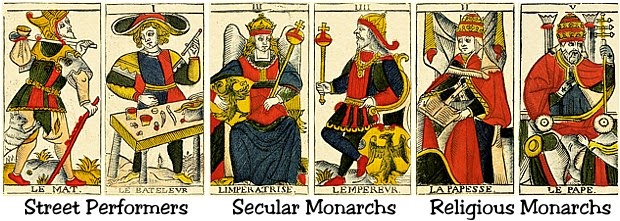

...all people of any kind, when they had to travel, used to go to the Inn of the Mirror, but for a long time they had preferred to go to that of the Fool, more appropriate to their will and their actions. This is why, with great mystery, we see the Fool in the game of Tarot being represented in such a way that he looks behind towards a mirror, making fun of the fame of [9] the Mirror, that is lost among all people, who once used to go to that inn. This is why his face is so joyful, he rejoices and glories in the credit he receives, so that all men run behind him. He is followed by the one that is called the Bagat, dressed as an innkeeper, not without subtlety, because as the signs of the Inns are seen by travelers before they see the innkeepers, and as the signs used to give good credit to the inns as we see in those of the Lilies, Eagles, Falcons, Crowns and Kings, that in all good and famous cities show good lodging, in the same way the Fool, being the figure of the inn, has been put before the Bagat, who is the Innkeeper, meaning that famous inn in which most people used to go.

The tenses in this passage drive me crazy. By the inn where they "used to go" at the end would be meant the inn they no longer go to, in my understanding of English, i.e. the Inn of the Mirror, as is clear. more or less, from the beginning of the part I have quoted. where it is said that people "used to go" to the Inn of the Mirror, but then preferred to go to the Inn of the Fool instead. Ross's footnote in the printed version explains that the Inn of the Looking-Glass is the Inn of prudence, since the Mirror is the attribute of Prudence, and the Inn of the Fool is the Inn of foolishness. So it comes out here that the Bagat, the innkeeper of the inn of prudence, would be the card of Prudence, similar to the old man in the Cebetis.

That's nice for my interpretation of the Bagat, but in all honesty I have to say that I wonder whether the published translation is correct. I am a rank amateur in Italian; I can't speak more than one word at a time, And the tenses baffle me. Nonetheless...

"Sogliano" would seem to be 3rd person present tense of "sogliare", meaning "to pass or go over the threshold of a door" (

http://www.pbm.com/~lindahl/florio/search/522c.html), rather than being equivalent to "solevano", imperfect of "solere" and meaning "used to". Also, the rest of the final clause looks to me a little messy. I prefer literal translations unless they make no sense. So for "così il Matto è stato anteposto come figura dell' hosteria al Bagato che è l' Hoste, per signficar ella esser quella famosa Hosteria nella qual la magior parte de gli huomini sogliano andar ad alloggiare" I read:

...so the Fool stands in front as the picture of the Inn of which the Bagato is the Innkeeper, to signify its being that famous Inn in which the majority of the people enter to go to lodge.

If so, he is the innkeeper of the inn where people go now, not the one where they used to go. The Fool is the sign out front--or in my city these days, the guy in the funny outfit waving his sign back and forth on the sidewalk to get my attention--and the Bagato is the Innkeeper of the Inn of which he is the picture, that of the Fool, foolishness. [Added next day: a problem with this translation is the adjective "famosa"; "fama" previously attached to the Inn of the Looking-glass. He would be contradicting what he said earlier. He's allowed to do that, but it requires explaining, e.g. the Inn of the Looking-Glass is no longer as famous as the Inn of the Fool.]

In either translation, the inns are a metaphor for life, which can be lived foolishly, on one side of the street, or prudently, on the other side. The two inns are those of the old Hermes Trismegistus character on the Fanti frontispiece, and--in the alternative translation I offer--that of the dice-rolling Hermes/Thoth next to him. If you choose the trickster Hermes, watch out. Like the Moon in Plutarch's story of the invention of gambling, you could lose some of your light, without help from a Trismegistus, an Agathodemon. But if you do lose, it's in a good cause. In that sense the old man in the Cebetis is not as good an approximation of the Bagat as the dice-roller plus old man in the Fanti. The Cebetis has the positive side, which I do want to emphasize even if it is not as good a fit.

While I'm at it, there are a few more places in the quote, further up, where I had trouble with the translation. One problem is with "voglia" at the beginning of the passage, which is translated as "had preferred". But WordReference says "voglia" is present tense subjunctive. However with the "but for a long time" makes "have preferred" more appropriate. Also, "accadendogli d' ir in viaggio " looks to me like "happening to travel" rather than "when they traveled"; the former is tenseless. And "perduta appresso tutti gl' huomini" looks to me like "lost with all the people", as I don't see "appresso" listed in WordReference as translated by "among". Except for "voglia", these are fine points, I know, but they make the passage more understandable. Also, since we are talking about an attribute of Prudence, I think "Looking-glass" is a more appropriate translation of "Specchio", since it connotes the hand-held thing associated with the virtue. So I get:

all people of every kind, happening to travel, used to lodge first at the inn of the Looking-glass, but for a long time have preferred to go to that of the Fool, more appropriate to their will and their actions. This is why, not without great mystery, we see the Fool in the game of Tarot being depicted in such a way that he looks behind [him] towards a mirror, making fun of the fame of [9] the Looking-glass lost with [in the sense of "dead to"] all the people who once used to go to that inn.

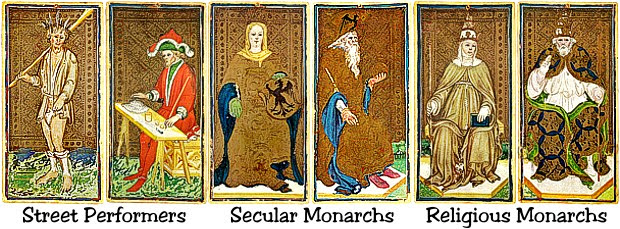

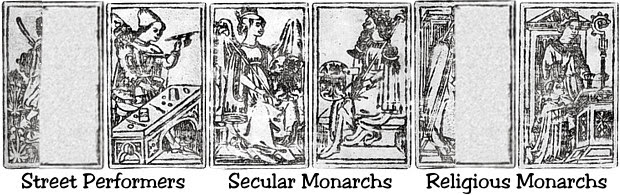

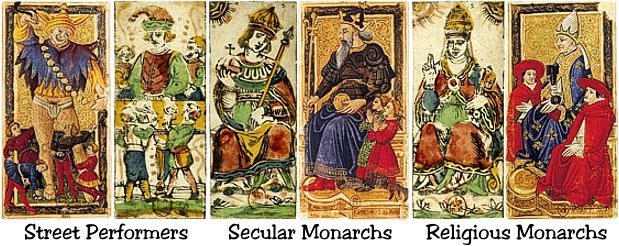

I imagine it as a Matto card like the ones of 17th or early 18th century Piedmont and Lombardy, the ones that sometimes had the French title "Le Fou", where his body is pointed away and to the right but he looks behind him. Piscina says he's looking at a card known for Fame; I can't help wondering it might even be called that. Since the Mirror = prudence, it is either trump 21, now called Prudence/Fame, or it is trump 14, which Alciato called "Fama", a word written on some Belgian Temperance cards, but perhaps here is the last trump in a deck with only 14. I imagine the cards in a circle, so that the last trump is behind the Fool. That's how the card is both zero and also, as in the Steele Sermon, can be the card talked about after the World. Of course all this is speculation. [Added next day: but the last card can't be 14, because Piscina goes on to describe all 22. With the published translation, it's simpler: he's simply looking at the Bagatto, across the street.]

The rest of the translation looks good. But what do I know? Please advise. [Added next day: please note that I made two changes, one at the end of the previous paragraph, and one earlier, regarding "famosa".]

(Hans Holbein the Younger illustration to Erasmus,

Praise of Folly, 1515 edition.)