I'm thinking that it was something to do with the etymology of the word carnival that derives it from carrus navalis, a term used for a float in an ancient Roman forerunner of carnival. That may only be a modern idea though.

I read the book in my youth, when I weren't able to evaluate the information and interpretation in a critical manner. At least I remember, that the book presented material to this question. It's a rather brutal interpretation.Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason, by Michel Foucault, is an examination of the ideas, practices, institutions, art and literature relating to madness in Western history. It is the abridged English edition of Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique, originally published in 1961 under the title Folie et déraison. Histoire de la folie à l'âge classique. A full translation titled The History of Madness was published by Routledge in June 2006.[1] This was Foucault's first major book, written while he was the Director of the Maison de France in Sweden.

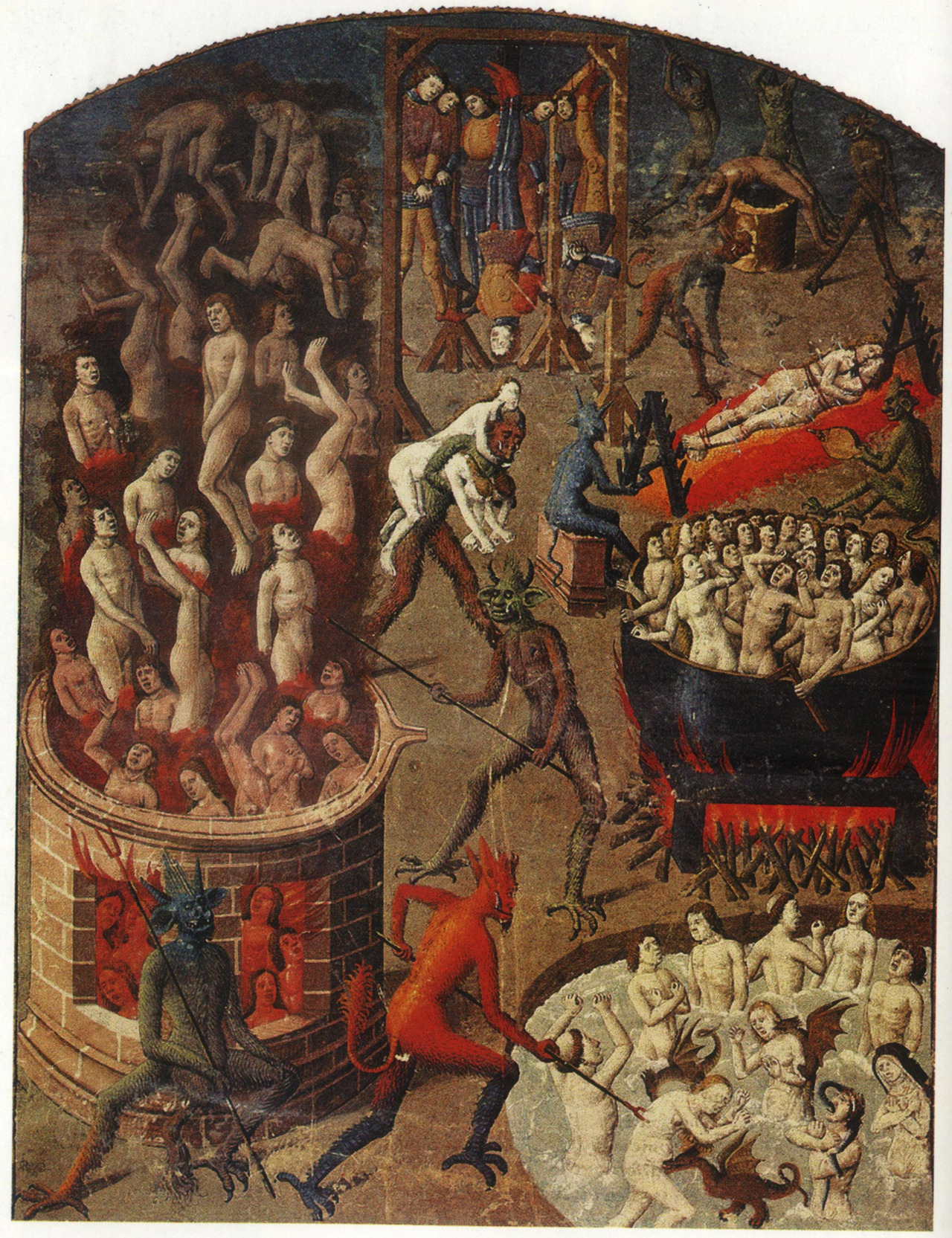

Foucault begins his history in the Middle Ages, noting the social and physical exclusion of lepers. He argues that with the gradual disappearance of leprosy, madness came to occupy this excluded position. The ship of fools in the 15th century is a literary version of one such exclusionary practice, the practice of sending mad people away in ships. However, during the Renaissance, madness was regarded as an all-abundant phenomenon because humans could not come close to the Reason of God. As Cervantes' Don Quixote, all humans are weak to desires and dissimulation. Therefore, the insane, understood as those who had come too close to God's Reason, were accepted in the middle of society. It is not before the 17th century, in a movement which Foucault famously describes as the Great Confinement, that "unreasonable" members of the population systematically were locked away and institutionalized. In the 18th century, madness came to be seen as the obverse of Reason, that is, as having lost what made them human and become animal-like and therefore treated as such. It is not before 19th century that madness was regarded as a mental illness that should be cured, e.g. Philippe Pinel, Freud. A few professional historians have argued that the large increase in confinement did not happen in 17th but in the 19th century.[2] Critics argue that this undermines the central argument of Foucault, notably the link between the Age of Enlightenment and the suppression of the insane.

However, Foucault scholars have shown that Foucault was not talking about medical institutions designed specifically for the insane but about the creation of houses of confinement for social outsiders, including not only the insane but also vagrants, unemployed, impoverished, and orphaned, and what effect those general houses of confinement had on the insane and perceptions of Madness in western society. Furthermore, Foucault goes to great lengths to demonstrate that while this "confinement" of social outcasts was a generally European phenomenon, it had a unique development in France and distinct developments in the other countries that the confinement took place in, such as Germany and England, disproving complaints that Foucault takes French events to generalize the history of madness in the West. A few of the historians critical of its historiography, such as Roy Porter, also began to concur with these refutations and discarded their own past criticisms to acknowledge the revolutionary nature of Foucault's book.[3]

Foucault also argues that madness during the Renaissance had the power to signify the limits of social order and to point to a deeper truth. This was silenced by the Reason of the Enlightenment. He also examines the rise of modern scientific and "humanitarian" treatments of the insane, notably at the hands of Philippe Pinel and Samuel Tuke. He claims that these modern treatments were in fact no less controlling than previous methods. Tuke's country retreat for the mad consisted of punishing them until they gave up their commitment to madness. Similarly, Pinel's treatment of the mad amounted to an extended aversion therapy, including such treatments as freezing showers and the use of straitjackets. In Foucault's view, this treatment amounted to repeated brutality until the pattern of judgment and punishment was internalized by the patient.

Im antiken Rom huldigten die Priester beim Festzug durch die Stadt ihrem Gott Bacchus in schiffartigen Wagen. Der erste für Köln nachgewiesene Umzug fand 1341 zu Ehren einer spätrömischen Göttin der Fruchtbarkeit und Schifffahrt ebenfalls in zu Schiffen umgebauten Wagen statt. Davon stammt die heute noch gängige Bezeichnung Narrenschiff.

Well .. Foucault's book looked well researched, but's it's too long ago that I read it. Generally the young cities had likely often the problem to get some not suitable persons out of it.Al Craig wrote:Thanks, Huck.

Not sure whether to believe Foucault. Venice might be a better idea because of its longstanding connection with carnival. Due to their lack of roads they would have had a reason to use real ships in their celebrations.

Where? I cant find it.I open a new thread about carnival

I found an online version of Foucault's book ...mmfilesi wrote:Where? I cant find it.I open a new thread about carnival

....

I dont remember why, but when I read (many years ago) the Foucault's bock, I dont think the "ship of fools" exists out the literary or picture reality.

....

In Italia seem usually use ships (as bucintoro) in the triumphal parades. See, for example, le nozze of constantio and Camilla or when Bianca arrives to Ferrara.

I had always wondered why those Italian players of the Game called the Hanged Man 'The Cheat'Lorredan wrote:That is very interesting Steve!

I was searching for some roots of the the word Cheat and found this

CHEAT

c.1375, aphetic of O.Fr. escheat, legal term for revision of property to state when owner dies without heirs, lit. "that which falls to one," pp. of escheoir "befall by chance, happen, devolve," from V.L. *excadere "to fall away," from L. ex- "out" + cadere "to fall" (see case (1)). Meaning evolved through "confiscate" (c.1440) to "deprive unfairly" (1590).

It seems to me that wrongdoing always has this sense of falling down, dropping down, upside down-The wrong way.

Which makes perfect sense of course.

The Italian for the Cheat is l'imbroglione (which is the term the players told me they called The Hanged Man)

Latin for cheat is impono - which has the sense of the little reverse

~Lorredan