This thread is dedicated to bringing together images of the works of Giovanni di Marco, aka Giovanni dal Ponte, from the 1420s and 1430s, as well as discussion of their relationship to the Rothschild cards in the Louvre and the Knight of Swords in the civic museum of Bassano del Grappa.

It should be useful since there is some controversy about the dating of these cards. There is also a question about the nature of the set: are they Tarot cards, which they are consistent with, or Imperatori, which we don't know the nature of? The implied question of "what was the game of Imperatori?" has more theories than theorists, since all of us can come up with several theories.

The main source is the 2016 catalogue edited by Lorenzo Sbaraglio and Angelo Tartuferi, Giovanni dal Ponte: Protagonista dell'umanesimo tardogotico fiorentino, held in Florence at the Galleria dell'Accademia, 22 November 2016 to 12 March 2017.

The list of his 93 known or attributed works, excluding controversial attributions and those not accepted by general consensus, is provided by Sbaraglio in the Regesto, pages 183-223 of the catalogue. 45 of the 93 are parts of formerly larger works like cassoni and altar retables, of which, when reconstituted, there are eight.

I don't intend to photograph the entire Regesto and post it, since only 47 works dating 1425-1435 (which could be 1437, since nothing is dated to the last years of his life, although we know he was working) concern us, as these dates are the dates in question for the Rothschild cards. Also, all or most them will be better from the internet than from the catalogue.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

2Here is the whole list of Sbaraglio's Regesto, simply giving the dates. I have analysed them into some different categories following the bare list.

01. 1415-1420

02. 1425-1430

03. 1425-1430

04. 1421

05. 1430 circa

06. 1425-1430

07. 1430 circa

08. 1415-1420

09. 1420-1425

10. 1420-1425

11. 1420-1425

12. 1410-1415

13. 1415-1420

14. 1415-1420

15. 1430 circa

16. 1430-1435

17. 1430 circa (part of 5)

18. 1415-1420

19. 1425-1430

20. 1434 (part of 64)

21. 1415-1420

22. 1420-1425

23. 1425-1430

24. 1415 circa

25. 1425-1430

26. 1425-1430

27. 1425-1430

28. 1420-1425

29. 1405-1410

30. 1430-1435

31. 1425-1430

32. 1405-1410

33. 1434 24 November

34. 1430-1435 (stained glass)

35. 1434 (fresco)

36. 1429-1432 (fresco)

37. 1430 circa

38. 1420-1425

39. 1410-1415

40. 1430-1435

41. 1415-1420

42. 1420-1425

43. 1425 circa

44. 1430 circa

45. 1430-1435

46. 1415-1420

47. 1420-1425

48. 1430 circa

49. 1420-1425

50. 1425-1430

51. 1425-1430

52. 1410-1415

53. 1420-1425

54. 1430-1435

55. 1430-1435

56. 1430-1435

57. 1425-1430

58. 1415-1420

59. 1430-1435

60. 1420-1425

61. 1420-1425

62. 1415-1420

63. 1435 26 March

64. 1434

65. 1430-1435

66. 1415-1420

67. 1410-1415

68. 1420-1425

69. 1415-1420

70. 1425-1430

71. 1420-1425

72. 1415-1420

73. 1410-1415

74. 1420-1425

75. 1415-1420

76. 1420-1425

77. 1420-1425

78. 1415-1420

79. 1425-1430

80. 1425-1430 (drawing)

81. 1425-1430

82. 1415-1420

83. 1430 circa

84. 1430 circa

85. 1430 circa

86. 1410-1415

87. 1430 circa

88. 1425-1430

89. 1430-1435

90. 1415-1420

91. 1415-1420

92. 1430 circa

93. 1405-1410

By period:

1405-1410

29, 32, 93

1410-1415

12, 39, 52, 67, 73, 86

1415-1420

01, 08, 13, 14, 18, 21, 24, 41, 46, 58, 62, 66, 69, 72, 75, 78, 82, 90, 91

1420-1425

04, 09, 10, 11, 22, 28, 38, 42, 47, 49, 53, 60, 61, 68, 71, 74, 76, 77

1425-1430

02, 03, 06, 19, 23, 25, 26, 27, 31, 43, 50, 51, 57, 70, 79, 80, 81, 88

1430-1435

05, 07, 15, 16, 17, 20, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 44, 45, 48, 54, 55, 56, 59, 63, 64, 65, 83, 84, 85, 87, 89, 92

Precisely dated

04 (1421), 20 (1434), 33 (1434), 35 (1434), 36 (1429-1432), 63 (1435), 64 (1434)

Works dated 1425-1430

02 Saint Anthony, abbot, part of polyptych with 03 and 79, Baltimore Museum of Art inv. n. 1951.391

03 Three compartments of 02 and 79, Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, inv.nn. 2572, 2573, 2574

06 Two tabernacle doors Sts. Jerome, John Baptist, Cambridge UK, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. n. 565

19 Madonna con Bambino, Firenze, collezione Gianfranco Luzzetti

23 Incoronazione della Vergine, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 n. 458

25 Two tabernacle doors San Giuliano, Giovanni battista, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 nn. 6232, 6105

26 Two tabernacle doors San Giacomo maggiore, Sant'Elena, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 nn. 8744, 8746

27 Madonna col Bambino in trono, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. s.n.

31 Two tabernacle doors, San Miniato, San Giovanni Gualberto, Firenze, abbazia di San Miniato al Monte, convento, cappella di San Benedetto

43 Triptych of Saint John the Evangelist, London, National Gallery, inv. n. NG580.9-12, circa 1425

50 Two tabernacle doors, Saints James the Greater, John the Baptist, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. 1959.15.7A-B

51 Cassone front panel, Love Garden, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. 1896.1943.217

57 Annunciation on separate cusps, Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. nn. 2014-82-1, 2014-82-2

70 Madonna dell'umiltà, location unknown (Florence 1946 in Volterra collection)

79 Madonna col Bambino tra due angeli, location unknown (Rome 1970 in Vitetti collection)

80 Drawing of two youths, due giovani, location unknown (Rotterdam private collection until 1940)

81 Madonna annunciata (frammento), location unknown (Christie's London, 23 November 1962, lot 77)

88 Madonna col Bambino, location unknown (Christie's New York, 28 January 2009, lot 3)

Works dated 1430-1435 “mature works”

Nothing dated precisely 1436-1437. Latest dated work number 63, 1435.

05 Madonna col Bambino, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. n. 551, circa 1430

07 Fragment of cassone, Cambridge, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg, inv. n. 1919.564, circa 1430 (part 87)

15 Fragment of cassone, Cracow, Museum Czartoryski, inv. n. 231, circa 1430 (part of 48, 83, 84, 85)

16 Digione (Francia), Musée des Beaux-Arts inv. n. 1182

17 Side-panel of Polittico di San Pietro, Fiesole, Museo Bandini, inv. 1862 n. 22; inv. 1914 n. 31, circa 1430 (part of 5, 37)

20 Battesimo di Cristo ed elemosina di san Nicola, Firenze, collezione privata, 1434

30 Annunciazione, Firenze, Palazzo Vecchio

33 Madonna col Bambino tra i santi Cecilia con la donatrice... Firenze, Musei civici fiorentini 1434

34 Deposizione dalla Croce, Firenze, basilica di Santa Croce...

35 Martirio di san Bartolomeo... Firenze, basilica di Santa Trinita, cappella Scali, 1434, with Smeraldo

36 San Pietro and others, same church, cappella Usimbardi, 1429-1432 with Smeraldo di Giovanni

37 Seven parts of Polittico di San Pietro, Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1890 n. 1620, circa 1430 (part of 5, 17)

40 Santi Nicola e Benedetto, Hannover, Niedersächsischen Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, inv. n. 278

44 Saint Thomas Aquinas, Domenico and Peter Martyr (?), Los Angeles, private collection, circa 1430

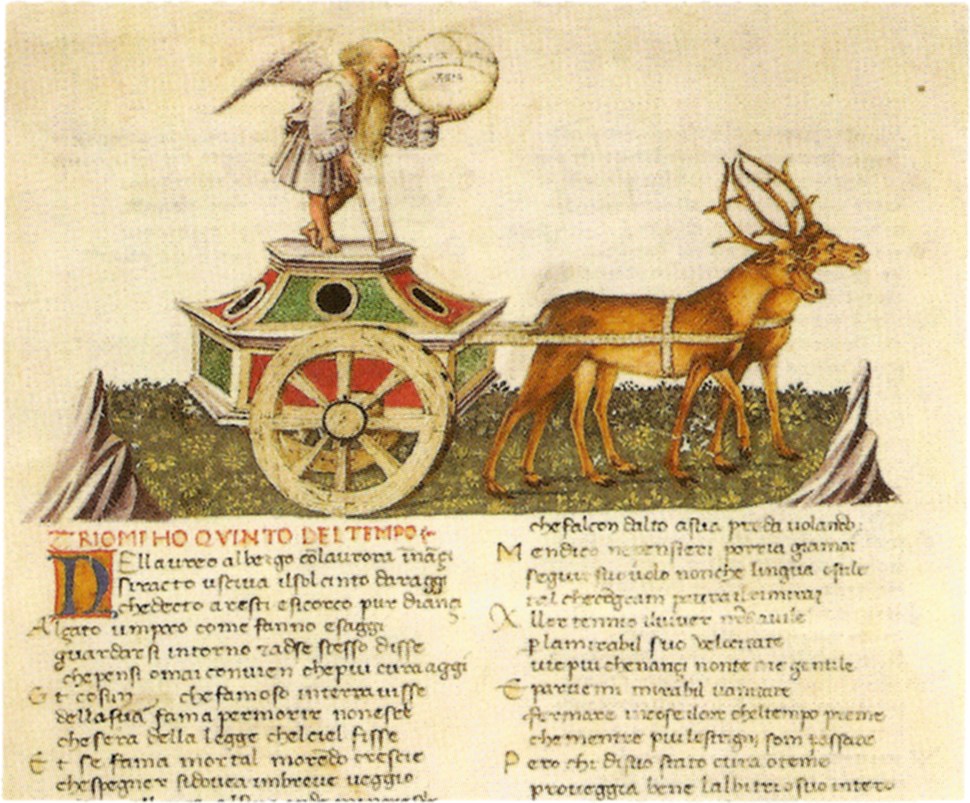

45 Allegoria delle sette arti liberali, Madrid, Museo del Prado, inv. n. 2844

48 Fragment of cassone front, Monaco, private collection, circa 1430 (part of 15, 83-85, 92)

54 Cassone, Giardino d'Amore, Parigi, Institut de Fr., Musée Jacquemart-André, inv. n. MJAP-M 1765

55 Annunciazione, Pescia (Pistoia), Museo Civico, Deposito delle Gallerie fiorentine, inv. 1890 n. 450

56 Santi Gimignano (?) e Francesco d'Assisi, Philadelphia, Ph. Museum of Art, inv. n. J 1739

59 Annuciazione... Poppiena (Pratovecchio-Stia, Arezzo), badia di Santa Maria a Popp. Altare a destra

63 Annunciazione, Roma, Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, inv. n. 11/85 depositi, 26 Mar 1435

64 Annunciazione, Rosano (Pontassieve, Firenze), chiesa dell'abbazia di S. Maria, dated 1434

65 Madonna in trono...San Francisco, M.H. De Young Memorial Museum, inv. n. 61-44-5

83 Fragment of cassone, Christie's, 8 December 1989, lot 89, circa 1430

84 Fragment of cassone, Sotheby's, 24 June 1953, lot 11, circa 1430

85 Fragment of cassone front, location unknown, Sotheby's 24 June 1953, lot 11, circa 1430

87 Fragment of cassone front, location unknown (NYC, American Art Association, 10 December 1024 (sic; 1924?), lot 31, circa 1430

89 Allegoria delle sette virtù, cassone panel, Christie's, 14 April 2016, lot 129

92 Fragments of cassone, auction Paris, Galerie Charpentier, 2 December 1954 lot 19-20, circa 1430

01. 1415-1420

02. 1425-1430

03. 1425-1430

04. 1421

05. 1430 circa

06. 1425-1430

07. 1430 circa

08. 1415-1420

09. 1420-1425

10. 1420-1425

11. 1420-1425

12. 1410-1415

13. 1415-1420

14. 1415-1420

15. 1430 circa

16. 1430-1435

17. 1430 circa (part of 5)

18. 1415-1420

19. 1425-1430

20. 1434 (part of 64)

21. 1415-1420

22. 1420-1425

23. 1425-1430

24. 1415 circa

25. 1425-1430

26. 1425-1430

27. 1425-1430

28. 1420-1425

29. 1405-1410

30. 1430-1435

31. 1425-1430

32. 1405-1410

33. 1434 24 November

34. 1430-1435 (stained glass)

35. 1434 (fresco)

36. 1429-1432 (fresco)

37. 1430 circa

38. 1420-1425

39. 1410-1415

40. 1430-1435

41. 1415-1420

42. 1420-1425

43. 1425 circa

44. 1430 circa

45. 1430-1435

46. 1415-1420

47. 1420-1425

48. 1430 circa

49. 1420-1425

50. 1425-1430

51. 1425-1430

52. 1410-1415

53. 1420-1425

54. 1430-1435

55. 1430-1435

56. 1430-1435

57. 1425-1430

58. 1415-1420

59. 1430-1435

60. 1420-1425

61. 1420-1425

62. 1415-1420

63. 1435 26 March

64. 1434

65. 1430-1435

66. 1415-1420

67. 1410-1415

68. 1420-1425

69. 1415-1420

70. 1425-1430

71. 1420-1425

72. 1415-1420

73. 1410-1415

74. 1420-1425

75. 1415-1420

76. 1420-1425

77. 1420-1425

78. 1415-1420

79. 1425-1430

80. 1425-1430 (drawing)

81. 1425-1430

82. 1415-1420

83. 1430 circa

84. 1430 circa

85. 1430 circa

86. 1410-1415

87. 1430 circa

88. 1425-1430

89. 1430-1435

90. 1415-1420

91. 1415-1420

92. 1430 circa

93. 1405-1410

By period:

1405-1410

29, 32, 93

1410-1415

12, 39, 52, 67, 73, 86

1415-1420

01, 08, 13, 14, 18, 21, 24, 41, 46, 58, 62, 66, 69, 72, 75, 78, 82, 90, 91

1420-1425

04, 09, 10, 11, 22, 28, 38, 42, 47, 49, 53, 60, 61, 68, 71, 74, 76, 77

1425-1430

02, 03, 06, 19, 23, 25, 26, 27, 31, 43, 50, 51, 57, 70, 79, 80, 81, 88

1430-1435

05, 07, 15, 16, 17, 20, 30, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 44, 45, 48, 54, 55, 56, 59, 63, 64, 65, 83, 84, 85, 87, 89, 92

Precisely dated

04 (1421), 20 (1434), 33 (1434), 35 (1434), 36 (1429-1432), 63 (1435), 64 (1434)

Works dated 1425-1430

02 Saint Anthony, abbot, part of polyptych with 03 and 79, Baltimore Museum of Art inv. n. 1951.391

03 Three compartments of 02 and 79, Brussels, Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, inv.nn. 2572, 2573, 2574

06 Two tabernacle doors Sts. Jerome, John Baptist, Cambridge UK, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. n. 565

19 Madonna con Bambino, Firenze, collezione Gianfranco Luzzetti

23 Incoronazione della Vergine, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 n. 458

25 Two tabernacle doors San Giuliano, Giovanni battista, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 nn. 6232, 6105

26 Two tabernacle doors San Giacomo maggiore, Sant'Elena, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. 1890 nn. 8744, 8746

27 Madonna col Bambino in trono, Firenze, Galleria dell'Accademia, inv. s.n.

31 Two tabernacle doors, San Miniato, San Giovanni Gualberto, Firenze, abbazia di San Miniato al Monte, convento, cappella di San Benedetto

43 Triptych of Saint John the Evangelist, London, National Gallery, inv. n. NG580.9-12, circa 1425

50 Two tabernacle doors, Saints James the Greater, John the Baptist, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. 1959.15.7A-B

51 Cassone front panel, Love Garden, New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, inv. 1896.1943.217

57 Annunciation on separate cusps, Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, inv. nn. 2014-82-1, 2014-82-2

70 Madonna dell'umiltà, location unknown (Florence 1946 in Volterra collection)

79 Madonna col Bambino tra due angeli, location unknown (Rome 1970 in Vitetti collection)

80 Drawing of two youths, due giovani, location unknown (Rotterdam private collection until 1940)

81 Madonna annunciata (frammento), location unknown (Christie's London, 23 November 1962, lot 77)

88 Madonna col Bambino, location unknown (Christie's New York, 28 January 2009, lot 3)

Works dated 1430-1435 “mature works”

Nothing dated precisely 1436-1437. Latest dated work number 63, 1435.

05 Madonna col Bambino, Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, inv. n. 551, circa 1430

07 Fragment of cassone, Cambridge, Harvard Art Museums, Fogg, inv. n. 1919.564, circa 1430 (part 87)

15 Fragment of cassone, Cracow, Museum Czartoryski, inv. n. 231, circa 1430 (part of 48, 83, 84, 85)

16 Digione (Francia), Musée des Beaux-Arts inv. n. 1182

17 Side-panel of Polittico di San Pietro, Fiesole, Museo Bandini, inv. 1862 n. 22; inv. 1914 n. 31, circa 1430 (part of 5, 37)

20 Battesimo di Cristo ed elemosina di san Nicola, Firenze, collezione privata, 1434

30 Annunciazione, Firenze, Palazzo Vecchio

33 Madonna col Bambino tra i santi Cecilia con la donatrice... Firenze, Musei civici fiorentini 1434

34 Deposizione dalla Croce, Firenze, basilica di Santa Croce...

35 Martirio di san Bartolomeo... Firenze, basilica di Santa Trinita, cappella Scali, 1434, with Smeraldo

36 San Pietro and others, same church, cappella Usimbardi, 1429-1432 with Smeraldo di Giovanni

37 Seven parts of Polittico di San Pietro, Firenze, Gallerie degli Uffizi, inv. 1890 n. 1620, circa 1430 (part of 5, 17)

40 Santi Nicola e Benedetto, Hannover, Niedersächsischen Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, inv. n. 278

44 Saint Thomas Aquinas, Domenico and Peter Martyr (?), Los Angeles, private collection, circa 1430

45 Allegoria delle sette arti liberali, Madrid, Museo del Prado, inv. n. 2844

48 Fragment of cassone front, Monaco, private collection, circa 1430 (part of 15, 83-85, 92)

54 Cassone, Giardino d'Amore, Parigi, Institut de Fr., Musée Jacquemart-André, inv. n. MJAP-M 1765

55 Annunciazione, Pescia (Pistoia), Museo Civico, Deposito delle Gallerie fiorentine, inv. 1890 n. 450

56 Santi Gimignano (?) e Francesco d'Assisi, Philadelphia, Ph. Museum of Art, inv. n. J 1739

59 Annuciazione... Poppiena (Pratovecchio-Stia, Arezzo), badia di Santa Maria a Popp. Altare a destra

63 Annunciazione, Roma, Città del Vaticano, Pinacoteca Vaticana, inv. n. 11/85 depositi, 26 Mar 1435

64 Annunciazione, Rosano (Pontassieve, Firenze), chiesa dell'abbazia di S. Maria, dated 1434

65 Madonna in trono...San Francisco, M.H. De Young Memorial Museum, inv. n. 61-44-5

83 Fragment of cassone, Christie's, 8 December 1989, lot 89, circa 1430

84 Fragment of cassone, Sotheby's, 24 June 1953, lot 11, circa 1430

85 Fragment of cassone front, location unknown, Sotheby's 24 June 1953, lot 11, circa 1430

87 Fragment of cassone front, location unknown (NYC, American Art Association, 10 December 1024 (sic; 1924?), lot 31, circa 1430

89 Allegoria delle sette virtù, cassone panel, Christie's, 14 April 2016, lot 129

92 Fragments of cassone, auction Paris, Galerie Charpentier, 2 December 1954 lot 19-20, circa 1430

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

3The first thing to notice is that the art historians use the "five-year rule," as being roughly close enough when a more precise date cannot be established. This has implications for the end of Giovanni's life, since he lived possibly as late as March 1438. We know he was commissioned, with three other artists, to paint three Apostles for the upcoming consecration of the Duomo of Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, in 1436. These paintings were replaced later with statues, which still decorate the facade of the cathedral.

In other words, the "mature works" dating of 1430-1435, since it is approximative, could actually be "1430-1437" for many of them, if nothing particularly distinguishes a work from 1430 and one from 1435 or later. In other words, the entire 1430s is one period of Giovanni's oeuvre. There is also one work, number 36 of the Regesto, which dates from 1429-1432, thus breaking the artifical five-year periodization.

The Duomo Apostles are attested as follows:

On 17 February 1436, Giovanni dal Ponte ("di Marco") was commissioned to paint three Apostles on the facade of Santa Maria del Fiore, in anticipation of the cathedral's consecration to be held on 25 March.

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... BLOCK4.HTM

Three other artists were commissioned with him:

Bicci di Giovanni

Lippo d'Andrea

Rossello di Jacopo Franchi

He was paid four gold florins that day -

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... LOCK00.HTM

He was paid three and a half gold florins, the remainder of his commission, on 19 March, -

The rate for each Apostle was 2 ½ florins.

On the identity of Bicci di Giovanni, he is named only once in the Duomo documents, and I can find nothing else about him. Cécile Maisonneuve, Florence au XVe siècle, un quartier et ses peintres (CTHS-INHA, 2012), helpfully identifies him as Bicci di Lorenzo:“... les documents de l'Opera del duomo relatifs à la réalisation des Apôtres pour Santa Maria del Fiore mettent en cause en 1436 Bicci di Lorenzo, Giovanni dal Ponte, Rossello di Jacopo et Lippo d'Andrea, puis en 1440 Bicci seul” (page 242).

Bicci di Lorenzo was in fact commissioned to paint three Apostles on 17 February 1436, when he is paid four gold florins, and paid the rest on 19 March 1436, three and a half gold florins “per resto di paghamento di tre apostoli pe(r) lui fatti in chiesa,” which only makes sense if he were the same Bicci commissioned on 17 February. So it seems that the 1436 Latin scribe was the one in error, perhaps by dittography, since the marginal register note says:

Pro Bib Biccio .............................

Rossello ...................................pictoribus

Iohanne Marci et ............................

Lippo .................

- to which the editors of the site add the note at “Bib” that “Followed by “Bib-”.” It is probably a mistake, miswriting “Bib” for “Bic.”

A second mistake is the name “Rossettum” (for Rossellum), which the editors note is “Such in the text.”

Bicci di Lorenzo's payments -

In other words, the "mature works" dating of 1430-1435, since it is approximative, could actually be "1430-1437" for many of them, if nothing particularly distinguishes a work from 1430 and one from 1435 or later. In other words, the entire 1430s is one period of Giovanni's oeuvre. There is also one work, number 36 of the Regesto, which dates from 1429-1432, thus breaking the artifical five-year periodization.

The Duomo Apostles are attested as follows:

On 17 February 1436, Giovanni dal Ponte ("di Marco") was commissioned to paint three Apostles on the facade of Santa Maria del Fiore, in anticipation of the cathedral's consecration to be held on 25 March.

Prefati operarii congregati ut supra eligerunt Biccium Iohannis, Iohannem Marci, Lippum et Rossettum pittores ad pingendum seu pingi faciendum in ecclesia maiori florentina duodecim apostolos pro consegratione fienda dicte ecclesie, et mutuentur eis floreni auri quattuor pro quolibet eorum.

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... BLOCK4.HTM

Three other artists were commissioned with him:

Bicci di Giovanni

Lippo d'Andrea

Rossello di Jacopo Franchi

He was paid four gold florins that day -

A Giovanni di Marcho dipintore fiorini quatro d'oro, e detti denari a·llui si prestano per dipingniere tre apostoli in chiesa, a· libro segnato D a c. 196

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... LOCK00.HTM

He was paid three and a half gold florins, the remainder of his commission, on 19 March, -

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... LOCK00.HTMA Giovanni di Marcho dipintore fiorini tre e mezo d'oro sono per resto di paghamento di tre apostoli pe· lui dipinti in chiesa pella chonsagrazione della chiesa a ragione di fiorini 2 1/2 per apostolo, a· libro segnato D a c. 196

The rate for each Apostle was 2 ½ florins.

On the identity of Bicci di Giovanni, he is named only once in the Duomo documents, and I can find nothing else about him. Cécile Maisonneuve, Florence au XVe siècle, un quartier et ses peintres (CTHS-INHA, 2012), helpfully identifies him as Bicci di Lorenzo:“... les documents de l'Opera del duomo relatifs à la réalisation des Apôtres pour Santa Maria del Fiore mettent en cause en 1436 Bicci di Lorenzo, Giovanni dal Ponte, Rossello di Jacopo et Lippo d'Andrea, puis en 1440 Bicci seul” (page 242).

Bicci di Lorenzo was in fact commissioned to paint three Apostles on 17 February 1436, when he is paid four gold florins, and paid the rest on 19 March 1436, three and a half gold florins “per resto di paghamento di tre apostoli pe(r) lui fatti in chiesa,” which only makes sense if he were the same Bicci commissioned on 17 February. So it seems that the 1436 Latin scribe was the one in error, perhaps by dittography, since the marginal register note says:

Pro Bib Biccio .............................

Rossello ...................................pictoribus

Iohanne Marci et ............................

Lippo .................

- to which the editors of the site add the note at “Bib” that “Followed by “Bib-”.” It is probably a mistake, miswriting “Bib” for “Bic.”

A second mistake is the name “Rossettum” (for Rossellum), which the editors note is “Such in the text.”

Bicci di Lorenzo's payments -

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... LOCK00.HTMA Bicci di Lorenzo dipintore fiorini IIII d'oro, e detti denari a·llui si prestano per dipingniere tre apostoli in chiesa, a· libro segnato D a c. 195

http://archivio.operaduomo.fi.it/cupola ... LOCK00.HTMA Bicci di Lorenzo dipintore fiorini tre e mezo d'oro per resto di paghamento di tre apostoli pe· lui fatti in chiesa pella consagrazione della chiesa a ragione di fiorini 2 1/2 per apostolo, a· libro segnato D a c. 195

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

4Now to put some meat on these bones.

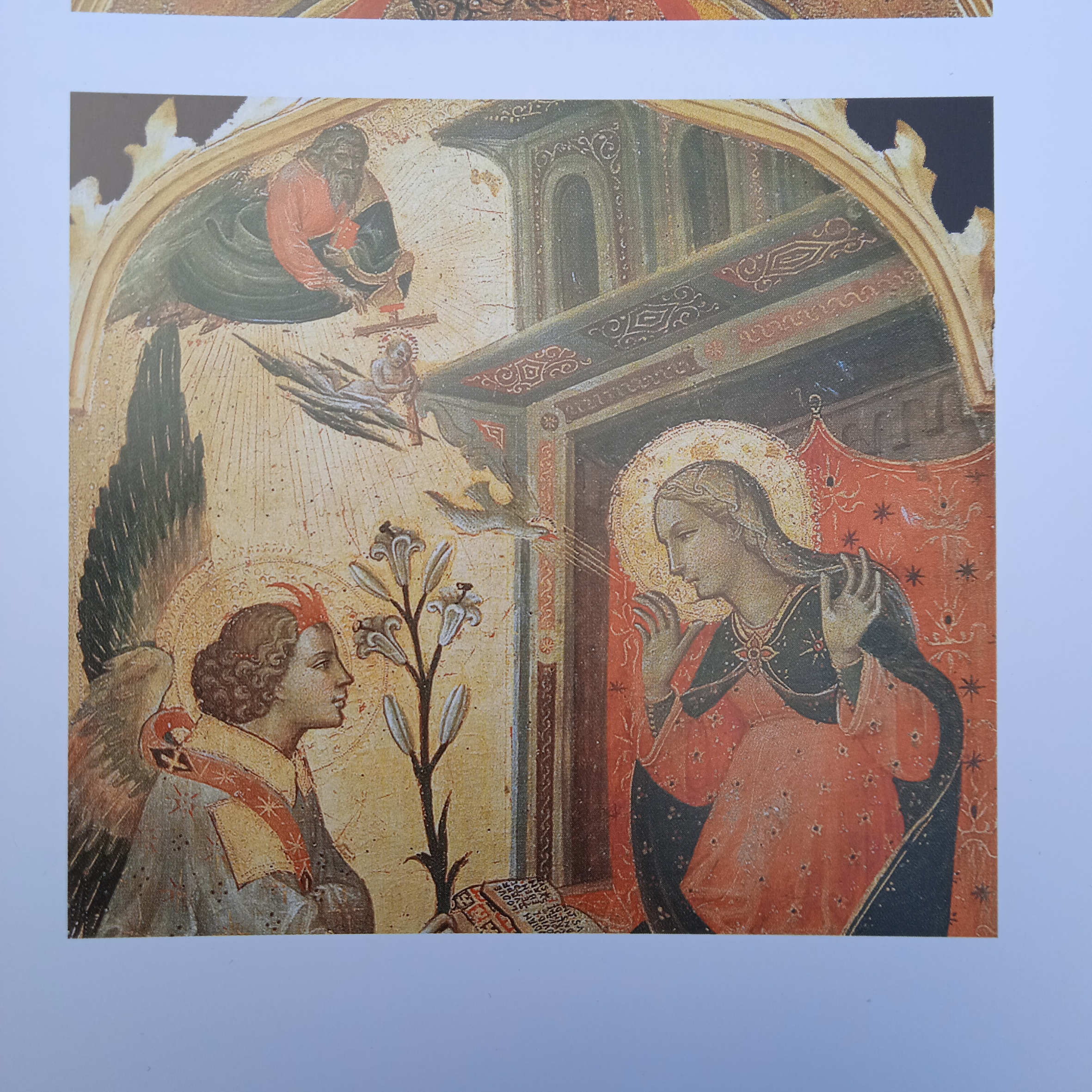

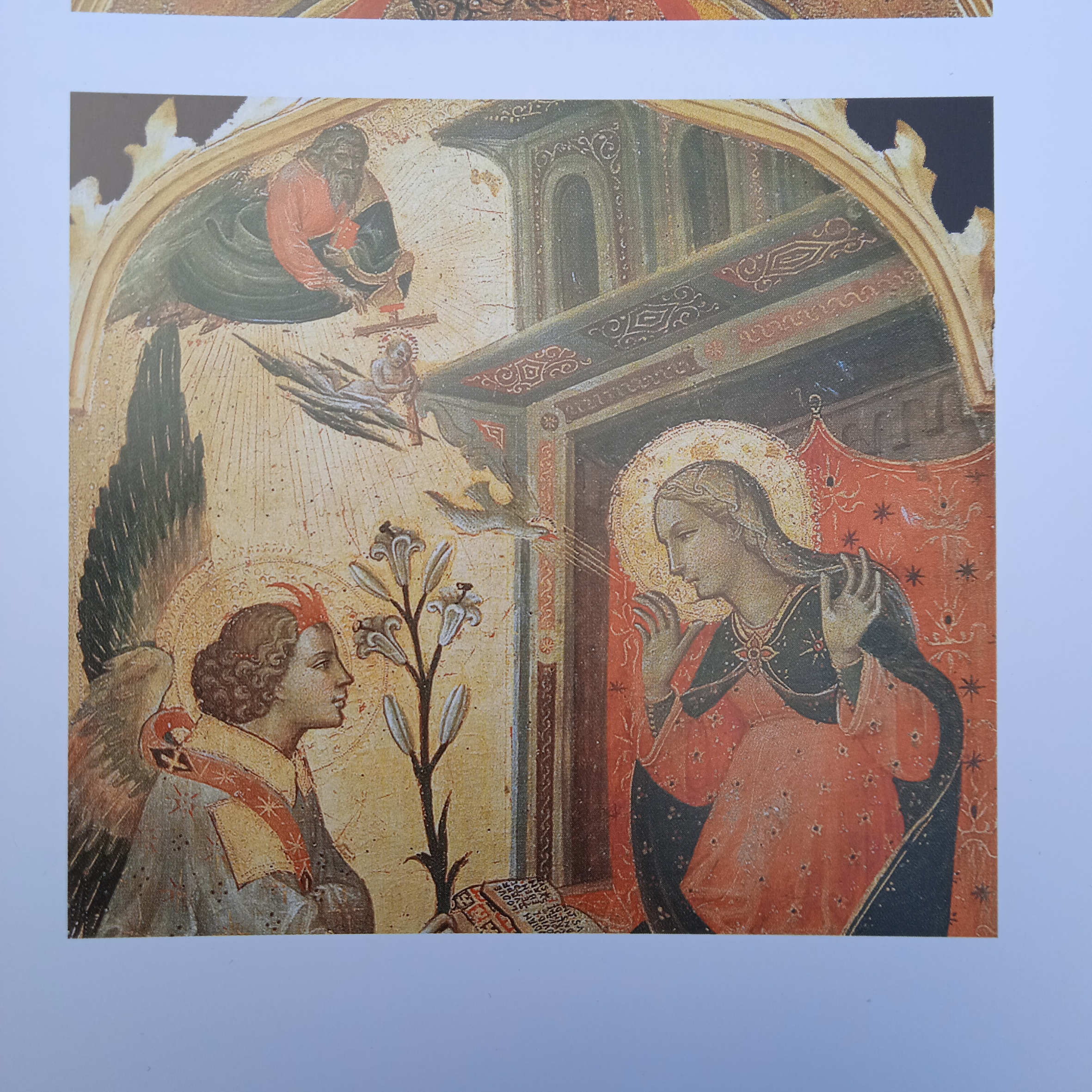

Annunciazione (detail), Rome, Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. The latest dated work of Giovanni's, 26 March 1435. Number 63 of the list.

Annunciazione (detail), Rome, Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. The latest dated work of Giovanni's, 26 March 1435. Number 63 of the list.

The earliest evidence for the game of Trionfi appears suddenly, in historical terms all at once, within two years, in the straight line from Florence, through Bologna, to Ferrara, and along the Po to Milan. This evidence includes the name of the game itself, custom-made hand-painted cards, and standard popular decks. From 1440 onward, there is scarcely a year when some record of it is not known, rapidly expanding so that within 15 years, it is known from Rome to Venice.

This is why I hold that the card game of Triumphs could not have been invented much earlier than 1440. And this is why I felt compelled to respond to Cristina Fiorini's dating of the Rothschild cards to 1422. Given how the evidence explodes as soon as it is known, 20 years of complete silence on the game (1442 was the earliest date we knew of in 2007) seemed incredibly unlikely.

So, I was pleased to find that Ada Labriola was able to attribute it to the late Giovanni di Marco, or even a close follower, rather than to the Giovanni of the early 1420s. This shows that there is sufficient subjectivity in a dating based on stylistic considerations to allow quite a wide margin. I have since learned that she remains displeased with this dating, preferring the 1425-1430 period, but felt constrained by the Tarot history evidence to push it as late as possible in Giovanni's career.

The purpose of this thread is to bring together the evidence we can gather on Giovanni's output from 1425 to the end of his career, in order to see if the late dating holds up. I think it does.

But there is the additional wrinkle of whether the Rothschild cards are Trionfi at all: could they be the otherwise obscure Imperatori?

This question seems to me to be irresolvable. There is no way to get at it without jumping immediately into speculation. The name alone, with or without the first instance of “VIII,” could very well mislead us by anachronism. That is, we are familiar with trump sequences, so it is easy to imagine that VIII Emperors were literally eight emperor cards added to the standard pack of cards. But trump cards are not common, much less sequences of trumps. We know only of two sequences: Marziano, and Trionfi or Tarot. Marziano had no progeny, whereas Tarot had many, from the expanded Visconti di Modrone, to Boiardo, to the Sola Busca, to Minchiate.

As for individual extra cards, whether they were wild cards or trumps, these appear to be more frequent in the history of card games globally. The earliest dated example I know of is Fernando de la Torre's Emperor, in his circa 1450 Juego de Naypes. He simply added this single extra card, “which beats all the others,” to the standard Spanish pack of 48 cards. He called the card “Emperador,” but made it depict the countess to whom he dedicated the game. Fernando is perhaps relevant to the question of Imperatori, since he finished his education in Florence in the years 1432 to 1434. Did he encounter there a similar game to the one he later invented? It seems entirely plausible.

But even if he did, this leaves unanswered the “VIII” of Imperatori, since there is only one emperor in his game. But there is also one emperor among the Rothschild cards. Thus, in order to connect the games of Fernando de la Torre, Rothschild, and Imperatori by this means, we have to immediately begin speculating about what the number VIII refers to, if it doesn't refer to a number of extra cards. Maybe it's a rule; maybe it's a collective name for different kinds of figures; maybe somebody added seven emperors more later than when Fernando met and played it. Maybe it's something else, about which there is plenty of theorizing here.

This is what I mean about the question being irresolvable to me. It just results in a mass of theory that rests on a very slim base, if on any base at all.

So I come to the point where I have to hold that if the Rothschild cards are Trionfi, they have to be dated as late as possible, even to the last year of Giovanni dal Ponte's life, or later if an imitator can be allowed (the style of his partner Smeraldo di Giovanni, known only from a couple of collaborative works with Giovanni, seems too different; also, Smeraldo, being 20 years older, seems unlikely to have imitated his junior companion). If they are not Trionfi, then of course they can be earlier than the late 1430s. They could be an example of the game that may have inspired Fernando de la Torre, with a single emperor card. Or, they could be Imperatori, with the caveat that we don't know what Imperatori cards were. I don't think the Rothschild were Imperatori cards.

But this thread is not about what the game of Imperatori was, it's about whether a late Giovanni dal Ponte dating for the Rothschild cards holds up stylistically. If it does, the Rothschild cards could be a fragmentary Trionfi pack, as they appear to be, and furthermore they would be the earliest surviving example of the game.

The Rothschild cards have now taken over the role that the Visconti di Modrone played for about 30 years. Before the chronology of the spread of Trionfi, and above all the pre-eminence of Florence, was clear, the possibility that the game was invented in Milan and the Visconti di Modrone represented its intial form before it evolved into the standard Tarot of the Visconti-Sforza, remained a viable theory. Now the dating and nature of the Rothschild cards has taken over the position as the bone of contention for early Tarot arguments.

The earliest evidence for the game of Trionfi appears suddenly, in historical terms all at once, within two years, in the straight line from Florence, through Bologna, to Ferrara, and along the Po to Milan. This evidence includes the name of the game itself, custom-made hand-painted cards, and standard popular decks. From 1440 onward, there is scarcely a year when some record of it is not known, rapidly expanding so that within 15 years, it is known from Rome to Venice.

This is why I hold that the card game of Triumphs could not have been invented much earlier than 1440. And this is why I felt compelled to respond to Cristina Fiorini's dating of the Rothschild cards to 1422. Given how the evidence explodes as soon as it is known, 20 years of complete silence on the game (1442 was the earliest date we knew of in 2007) seemed incredibly unlikely.

So, I was pleased to find that Ada Labriola was able to attribute it to the late Giovanni di Marco, or even a close follower, rather than to the Giovanni of the early 1420s. This shows that there is sufficient subjectivity in a dating based on stylistic considerations to allow quite a wide margin. I have since learned that she remains displeased with this dating, preferring the 1425-1430 period, but felt constrained by the Tarot history evidence to push it as late as possible in Giovanni's career.

The purpose of this thread is to bring together the evidence we can gather on Giovanni's output from 1425 to the end of his career, in order to see if the late dating holds up. I think it does.

But there is the additional wrinkle of whether the Rothschild cards are Trionfi at all: could they be the otherwise obscure Imperatori?

This question seems to me to be irresolvable. There is no way to get at it without jumping immediately into speculation. The name alone, with or without the first instance of “VIII,” could very well mislead us by anachronism. That is, we are familiar with trump sequences, so it is easy to imagine that VIII Emperors were literally eight emperor cards added to the standard pack of cards. But trump cards are not common, much less sequences of trumps. We know only of two sequences: Marziano, and Trionfi or Tarot. Marziano had no progeny, whereas Tarot had many, from the expanded Visconti di Modrone, to Boiardo, to the Sola Busca, to Minchiate.

As for individual extra cards, whether they were wild cards or trumps, these appear to be more frequent in the history of card games globally. The earliest dated example I know of is Fernando de la Torre's Emperor, in his circa 1450 Juego de Naypes. He simply added this single extra card, “which beats all the others,” to the standard Spanish pack of 48 cards. He called the card “Emperador,” but made it depict the countess to whom he dedicated the game. Fernando is perhaps relevant to the question of Imperatori, since he finished his education in Florence in the years 1432 to 1434. Did he encounter there a similar game to the one he later invented? It seems entirely plausible.

But even if he did, this leaves unanswered the “VIII” of Imperatori, since there is only one emperor in his game. But there is also one emperor among the Rothschild cards. Thus, in order to connect the games of Fernando de la Torre, Rothschild, and Imperatori by this means, we have to immediately begin speculating about what the number VIII refers to, if it doesn't refer to a number of extra cards. Maybe it's a rule; maybe it's a collective name for different kinds of figures; maybe somebody added seven emperors more later than when Fernando met and played it. Maybe it's something else, about which there is plenty of theorizing here.

This is what I mean about the question being irresolvable to me. It just results in a mass of theory that rests on a very slim base, if on any base at all.

So I come to the point where I have to hold that if the Rothschild cards are Trionfi, they have to be dated as late as possible, even to the last year of Giovanni dal Ponte's life, or later if an imitator can be allowed (the style of his partner Smeraldo di Giovanni, known only from a couple of collaborative works with Giovanni, seems too different; also, Smeraldo, being 20 years older, seems unlikely to have imitated his junior companion). If they are not Trionfi, then of course they can be earlier than the late 1430s. They could be an example of the game that may have inspired Fernando de la Torre, with a single emperor card. Or, they could be Imperatori, with the caveat that we don't know what Imperatori cards were. I don't think the Rothschild were Imperatori cards.

But this thread is not about what the game of Imperatori was, it's about whether a late Giovanni dal Ponte dating for the Rothschild cards holds up stylistically. If it does, the Rothschild cards could be a fragmentary Trionfi pack, as they appear to be, and furthermore they would be the earliest surviving example of the game.

The Rothschild cards have now taken over the role that the Visconti di Modrone played for about 30 years. Before the chronology of the spread of Trionfi, and above all the pre-eminence of Florence, was clear, the possibility that the game was invented in Milan and the Visconti di Modrone represented its intial form before it evolved into the standard Tarot of the Visconti-Sforza, remained a viable theory. Now the dating and nature of the Rothschild cards has taken over the position as the bone of contention for early Tarot arguments.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

5The reason I posted Giovanni's latest dated work is because of a detail. The interlaced spiral or Ss around the doorframe behind Mary. These are identical to those on the Rothschild, Charles VI, Catania, and Palermo cards.

Comparison of 1435 Annunciazione borders to Rothschild card border -

Giovanni did many Annunciations over his life, often on the same model, but this is the only place where this particular design around the doorframe is found. It is the only place I can find it in any of his works.

The borders of the four sets overall are identical. Here is a compilation -

Because of the Vecchio with hourglass, the Charles VI and Catania must date from the 1450s at the earliest (Simona Cohen's work is the authority here). It seems highly unlikely to me that, given the stylistic similarities I noted above, there could be a 25 year gap or greater between the Rothschild and the other two productions. Of course Cohen didn't comment on the Trionfi cards as examples of the Time genre, and she could not have known that they were Florentine in any case. So she may be wrong that this feature only appears with the Petrarchan Trionfi of the 1450s; it may have been invented by the same artists earlier, and the Tarot Vecchio himself is the earliest attestation of the attribution. Thus, if we can put the Catania and Charles VI cards in the 1440s, and the Rothschild in the late 1430s, there may be a difference of only a few years, which is plausible for this distinctive border style.

Because of the Vecchio with hourglass, the Charles VI and Catania must date from the 1450s at the earliest (Simona Cohen's work is the authority here). It seems highly unlikely to me that, given the stylistic similarities I noted above, there could be a 25 year gap or greater between the Rothschild and the other two productions. Of course Cohen didn't comment on the Trionfi cards as examples of the Time genre, and she could not have known that they were Florentine in any case. So she may be wrong that this feature only appears with the Petrarchan Trionfi of the 1450s; it may have been invented by the same artists earlier, and the Tarot Vecchio himself is the earliest attestation of the attribution. Thus, if we can put the Catania and Charles VI cards in the 1440s, and the Rothschild in the late 1430s, there may be a difference of only a few years, which is plausible for this distinctive border style.

For comparison, note that the Bembo workshop produced the Visconti di Modrone and Brambilla packs within two or three years of each other, but their borders are completely different. And the Ercole d'Este Tarocchi, now also held to be Florentine, but dating around 1473, has another kind of border entirely.

I think it is unreasonable to hold that this border style could have been identical in Florence for 30 years at least, from the 1420s through the 1450s, among different artists in different workshops. There has to have been some relationship, and thus some contemporaneity, between the Charles VI, Catania, Palermo, and the Rothschild cards artists.

Comparison of 1435 Annunciazione borders to Rothschild card border -

Giovanni did many Annunciations over his life, often on the same model, but this is the only place where this particular design around the doorframe is found. It is the only place I can find it in any of his works.

The borders of the four sets overall are identical. Here is a compilation -

For comparison, note that the Bembo workshop produced the Visconti di Modrone and Brambilla packs within two or three years of each other, but their borders are completely different. And the Ercole d'Este Tarocchi, now also held to be Florentine, but dating around 1473, has another kind of border entirely.

I think it is unreasonable to hold that this border style could have been identical in Florence for 30 years at least, from the 1420s through the 1450s, among different artists in different workshops. There has to have been some relationship, and thus some contemporaneity, between the Charles VI, Catania, Palermo, and the Rothschild cards artists.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

6I don't have anything to weigh in on for your main theory - its certainly a fairly radical redating (especially of the "CVI" - a problem for dating that one too early: viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1159 ) - but I do have something for you on Dal Ponte and the "Vecchio".Ross Caldwell wrote: 05 May 2022, 17:57 Because of the Vecchio with hourglass, the Charles VI and Catania must date from the 1450s at the earliest (Simona Cohen's work is the authority here). It seems highly unlikely to me that, given the stylistic similarities I noted above, there could be a 25 year gap or greater between the Rothschild and the other two productions. Of course Cohen didn't comment on the Trionfi cards as examples of the Time genre, and she could not have known that they were Florentine in any case. So she may be wrong that this feature only appears with the Petrarchan Trionfi of the 1450s; it may have been invented by the same artists earlier, and the Tarot Vecchio himself is the earliest attestation of the attribution. Thus, if we can put the Catania and Charles VI cards in the 1440s, and the Rothschild in the late 1430s, there may be a difference of only a few years, which is plausible for this distinctive border style.

From this 2017 thread - Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards viewtopic.php?p=18903#p18903 (page 5 or 13 Feb 2017, 12:25) - you can read my full interpretation of this odd "allegory", but the briefer conclusion here:

Apollo on the upper left, happily reigning while playing music, the Cumaean Sibyl pointing to her book of prophecy in the upper right, and below them in the middle is Time-as-Saturn, returned god of the Golden Age, crowning the mask of the Morelli, whose generations will see to the protection of their own line and that of Florence.

You'll note neither hourglass nor any other time indicator - just crutches. And this is arguably late in his career. I tried to confirm with the Cini Palazzo museo in Venice that they still have it (last reported place), in order to get a color version, but no response: http://www.palazzocini.it/en/

One other dal Ponte work that might have to do with time. I'm not sure why Charity, of the seven virtues in this dal Ponte cassone panel, has as her exemplum an astronomer (Ptolemy?), but the armillary sphere would seem yet another way to portray time:

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5986932 One thing I would odd note about this one, is the astronomer wears a headdress that is similar to what Emperor Sigismund wore, so perhaps after 1433 when he was crowned? But why associate the Empire with Charity? That Sigismund is intended seems fairly certain - compare the fresco in Malatesta's palazzo in Rimini, 'Gismondo praying to his namesake saint, who is painted like Emperor Sigismund and in the exact same attitude as the cassone figure (perhaps we can segue back to Imperatori here ;-): https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... und_03.jpg Perhaps the cassone is tied to a contemporary if fleeting peace agreement in the 1430s that the Empire tried to broker. All of the other exempli wear headdresses that are more typical of Florence and are being crowned with laurel - you can't even make out the laurel crown on "Ptolemy", although a similar putto makes the same crowning gesture on his head.

Phaeded

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

7Time is crippled and has wings .... it's slow (crippled) and quick (wings)

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

8Ross,

I'm currently not in a position time-wise to attempt to explore this issue in depth, but I'm certainly pleased that you are doing so, and I'm interested to see what other evidence you will present. My only contributions at the moment are a couple of critical notes on what you have presented thus far, and a very brief summary of the other side of the Rothschild dating argument.

In 2000, she said, "An important attribute of Time, the hourglass, seems to have made its first appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo about 1450." ("The early Renaissance personification of Time and changing concepts of temporality," Renaissance Studies 14 no. 3 (2000), p. 311). Even that statement was not particularly categorical, and left open the possibility of a date in the 1440s. Fourteen years later, in her book Transformations of Time and Temporality in Medieval and Renaissance Art (Leiden: Brill, 2014), she went further: "The hourglass as a symbol of time made its first appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo by 1450, as seen in the Florentine cassone from this period where it is carried on the back of Father Time (Fig. 42). This cassone is closely linked to those dating between 1440 and 1450, especially to the Pesellino panels in Boston (Fig. 43)." In other words, that early cassone painting showing Time with an hourglass on his back is datable to the 1440s. This is fairly obvious when you look at it and compare it with several others known to be from that decade.

So the presence of the hourglass is no obstacle to dating the Catania or Charles VI decks to the 1440s. However, the art-historical evidence might be. As you are probably aware, Ada Labriola, in her article "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle" in the Tarots Enluminés catalog, dated the Catania deck to around 1450 (p. 118) and the Charles VI to around 1460 (p. 120). Unless we have some good reason to doubt that (and I do not currently know of any), this means the borders you have found on the cards were probably in use for more than 20 years. It could easily be 25 years, even if the Rothschild deck is from the late 1430s. This is not at all surprising, because playing card design tends to be extremely conservative—and indeed the Catania and Charles VI decks bear that out, with some cards looking almost identical despite a gap of probably a decade between them. So it seems perfectly plausible to me that this border could have been in use on playing cards for 30 years, or even longer.

I wish I could get you excited about the possibility that they are Imperatori! To me, the prospect that the Rothschild cards could be our sole suriviving example of an Imperatori deck is far more thrilling than the possibility that they could be another early example of Florentine tarot, even if they were the earliest such example...

But, of course, we both need to try to stop ourselves being swayed by our personal preferences and focus on the evidence instead. You have begun to present evidence for a later dating of the Rothschild cards. To balance that, I can point to the evidence for an earlier dating, in the 1420s:

As summarized by Ada Labriola in "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle" (p. 117), all the Italian art historians who have examined the Rothschild cards have preferred a date in the 1420s for them: Christina Fiorini, Emanuele Zappasodi, and of course Ada herself. This is a lot to argue against, I think.

In addition to Ada's article, there are also the points made by Mike and myself in favour of an earlier Rothschild dating in the following thread, based on the artwork and (in my case) comparisons with other early playing cards: viewtopic.php?p=24544#p24544

So there are some fairly solid reasons to think the Rothschild deck is indeed from the third decade of the fifteenth century, and therefore probably too early to be a Trionfi deck.

I'm currently not in a position time-wise to attempt to explore this issue in depth, but I'm certainly pleased that you are doing so, and I'm interested to see what other evidence you will present. My only contributions at the moment are a couple of critical notes on what you have presented thus far, and a very brief summary of the other side of the Rothschild dating argument.

A week ago I had reason to re-examine what Simona Cohen had to say about that hourglass, and I found that her dating of the first appearance of the hourglass in depictions of Time to 1450 is far less firm than it has usually been regarded in discussions on this forum; in fact, she eventually revised her view and dated it to before 1450.Ross Caldwell wrote: 05 May 2022, 17:57 Because of the Vecchio with hourglass, the Charles VI and Catania must date from the 1450s at the earliest (Simona Cohen's work is the authority here).

In 2000, she said, "An important attribute of Time, the hourglass, seems to have made its first appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo about 1450." ("The early Renaissance personification of Time and changing concepts of temporality," Renaissance Studies 14 no. 3 (2000), p. 311). Even that statement was not particularly categorical, and left open the possibility of a date in the 1440s. Fourteen years later, in her book Transformations of Time and Temporality in Medieval and Renaissance Art (Leiden: Brill, 2014), she went further: "The hourglass as a symbol of time made its first appearance in the Trionfo del Tempo by 1450, as seen in the Florentine cassone from this period where it is carried on the back of Father Time (Fig. 42). This cassone is closely linked to those dating between 1440 and 1450, especially to the Pesellino panels in Boston (Fig. 43)." In other words, that early cassone painting showing Time with an hourglass on his back is datable to the 1440s. This is fairly obvious when you look at it and compare it with several others known to be from that decade.

So the presence of the hourglass is no obstacle to dating the Catania or Charles VI decks to the 1440s. However, the art-historical evidence might be. As you are probably aware, Ada Labriola, in her article "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle" in the Tarots Enluminés catalog, dated the Catania deck to around 1450 (p. 118) and the Charles VI to around 1460 (p. 120). Unless we have some good reason to doubt that (and I do not currently know of any), this means the borders you have found on the cards were probably in use for more than 20 years. It could easily be 25 years, even if the Rothschild deck is from the late 1430s. This is not at all surprising, because playing card design tends to be extremely conservative—and indeed the Catania and Charles VI decks bear that out, with some cards looking almost identical despite a gap of probably a decade between them. So it seems perfectly plausible to me that this border could have been in use on playing cards for 30 years, or even longer.

This is an odd statement, because you just asserted immediately before that we don't know what the Imperatori cards were. So it follows that the Rothshild cards could be Imperatori cards, and you don't seem to provide any reason for concluding that they are not. I am left with the impression that the only reason for your conclusion is that you would personally prefer them not to be...I don't think the Rothschild were Imperatori cards.

I wish I could get you excited about the possibility that they are Imperatori! To me, the prospect that the Rothschild cards could be our sole suriviving example of an Imperatori deck is far more thrilling than the possibility that they could be another early example of Florentine tarot, even if they were the earliest such example...

But, of course, we both need to try to stop ourselves being swayed by our personal preferences and focus on the evidence instead. You have begun to present evidence for a later dating of the Rothschild cards. To balance that, I can point to the evidence for an earlier dating, in the 1420s:

As summarized by Ada Labriola in "Les tarots peints à Florence au XVe siècle" (p. 117), all the Italian art historians who have examined the Rothschild cards have preferred a date in the 1420s for them: Christina Fiorini, Emanuele Zappasodi, and of course Ada herself. This is a lot to argue against, I think.

In addition to Ada's article, there are also the points made by Mike and myself in favour of an earlier Rothschild dating in the following thread, based on the artwork and (in my case) comparisons with other early playing cards: viewtopic.php?p=24544#p24544

So there are some fairly solid reasons to think the Rothschild deck is indeed from the third decade of the fifteenth century, and therefore probably too early to be a Trionfi deck.

Last edited by Nathaniel on 06 May 2022, 09:39, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

9I can't get anything from that thread that poses a solid challenge to dating Charles VI to the 1440s. The embroidered "FANTE" on the Fante of Swords' leg?Phaeded wrote: 06 May 2022, 02:20 I don't have anything to weigh in on for your main theory - its certainly a fairly radical redating (especially of the "CVI" - a problem for dating that one too early: viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1159 ) - but I do have something for you on Dal Ponte and the "Vecchio".

But I'm really not sure if anything prevents dating the three related sets of Catania, Palermo, and Charles VI earlier. Maybe it's because of the dates of the workshop of Apollonio di Giovanni and Marco del Buono (who was Lo Scheggia's partner prior to 1439).

My main point is that the borders of all these cards, including Rothschild, and other identical features like the imperial crowns and scepters, show that they were using the same models.

30 years is just too much time for different artists and workshops to produce these startling identical features. They have to be brought together in time. If Giovanni di Marco's death by early 1438 is the strongest control on the dating, then Catania, Palermo, and Charles VI have to be brought closer. I'm comfortable with a decade, but that means bringing them down to the late 1440s at the latest.

I'm going to take this impresa allegorica con stemma as one of the obsolete or controversial identifications, which is why Sbaraglio omits it from the catalogue. The Fondazione Zeri site doesn't say who identifies the artist as Giovanni di Marco, perhaps just the cataloguer. The only thing that vaguely resembles his work to my eye is the squat face of Time. But nothing else in the painting does.From this 2017 thread - Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards viewtopic.php?p=18903#p18903 (page 5 or 13 Feb 2017, 12:25) - you can read my full interpretation of this odd "allegory", but the briefer conclusion here:

Apollo on the upper left, happily reigning while playing music, the Cumaean Sibyl pointing to her book of prophecy in the upper right, and below them in the middle is Time-as-Saturn, returned god of the Golden Age, crowning the mask of the Morelli, whose generations will see to the protection of their own line and that of Florence.

You'll note neither hourglass nor any other time indicator - just crutches. And this is arguably late in his career. I tried to confirm with the Cini Palazzo museo in Venice that they still have it (last reported place), in order to get a color version, but no response: http://www.palazzocini.it/en/

He should have been dead before this allegory was invented in any case. The earliest dated example is this manuscript version of Petrarch's Triumph of Time, 1442

Of course we could theorize that the allegory was invented by 1437, and appeared in the earliest Tarot, one of which was painted by Giovanni dal Ponte... or, it could have originally been nothing more than a decrepit vecchio in the Tarot, not an allegory of Time, only later becoming conflated with that Petrarchan subject.

I can't find an explanation for that figure either. Pesellino's version of the same subjects in the same style has completely different exemplars, and Caritas has Saint Paul. Dal Ponte's are a strange mix. The figure with Faith has a halo, but also a sword. Is it Constantine? Charlemagne? The figure with Hope I can't identify at all. I think the figure with Charity is holding a book, but I can't be sure it's an astronomical thingy on the cover. Maybe it's a cross? Probably someone in the long bibliography on the Christie's site where it was sold in 2016 will have some discussion.One other dal Ponte work that might have to do with time. I'm not sure why Charity, of the seven virtues in this dal Ponte cassone panel, has as her exemplum an astronomer (Ptolemy?), but the armillary sphere would seem yet another way to portray time:

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5986932

dal Ponte Charity - Sigismund-Astronomer sphere.jpg

One thing I would odd note about this one, is the astronomer wears a headdress that is similar to what Emperor Sigismund wore, so perhaps after 1433 when he was crowned? But why associate the Empire with Charity? That Sigismund is intended seems fairly certain - compare the fresco in Malatesta's palazzo in Rimini, 'Gismondo praying to his namesake saint, who is painted like Emperor Sigismund and in the exact same attitude as the cassone figure (perhaps we can segue back to Imperatori here ;-): https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... und_03.jpg Perhaps the cassone is tied to a contemporary if fleeting peace agreement in the 1430s that the Empire tried to broker. All of the other exempli wear headdresses that are more typical of Florence and are being crowned with laurel - you can't even make out the laurel crown on "Ptolemy", although a similar putto makes the same crowning gesture on his head.

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5986932

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte and Rothschild cards dating

10As I indicated above, I disagree, on the grounds of the conservatism of playing card design. It seems quite plausible to me that these features could indeed have been preserved over that length of time, simply by the artists copying the cards that came before.Ross Caldwell wrote: 06 May 2022, 09:38 30 years is just too much time for different artists and workshops to produce these startling identical features. They have to be brought together in time.