I took a roundabout way in coming to this conclusion, starting with ecclesiastical writers.

It didn't seem like something any Church Father or medieval theologians would have done, since these three colors don't appear together in the Bible; if they had, in a positive way (as opposed to the diseases of clothing and houses in Leviticus 13 and 14, where "greenish" and "reddish" appear as symtoms), they could have been interpreted allegorically, and that might have been the origin of the association. But it isn't.

My next tack was with Church symbolism, the Ecclesiastical colors. Writers who interpreted liturgical symbolism (and often had a hand in creating it), based themselves in the Bible, particularly the description of the Temple furniture and priestly garments, and the Song of Songs (for sponsus-sponsa symbolism).

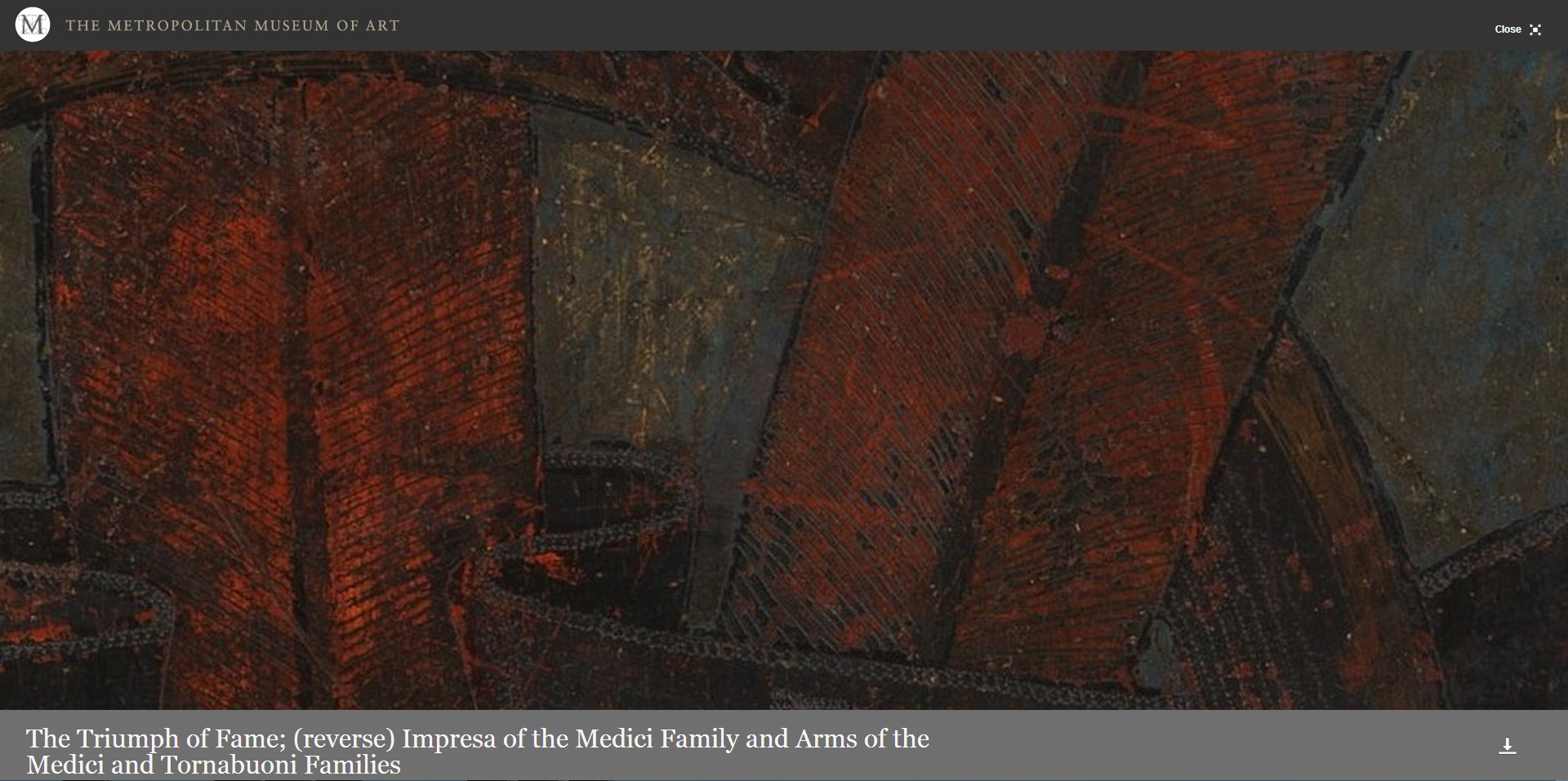

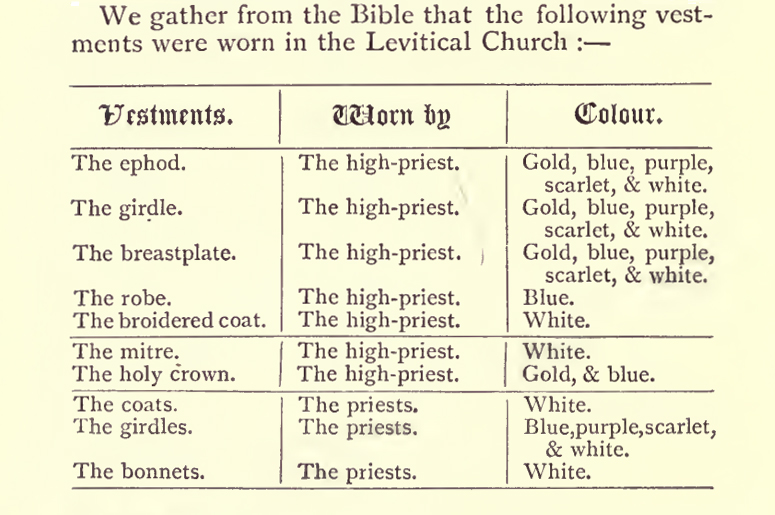

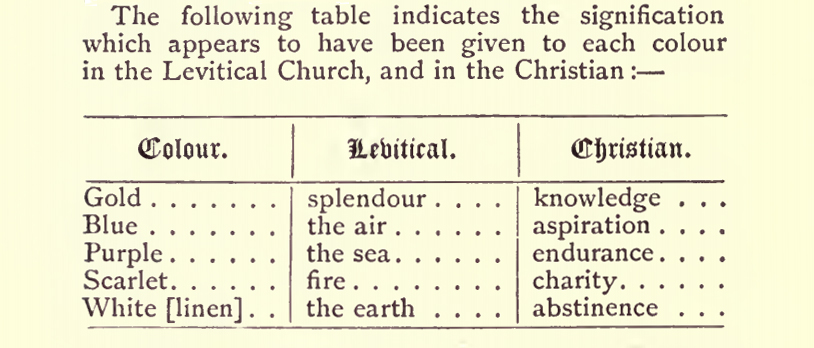

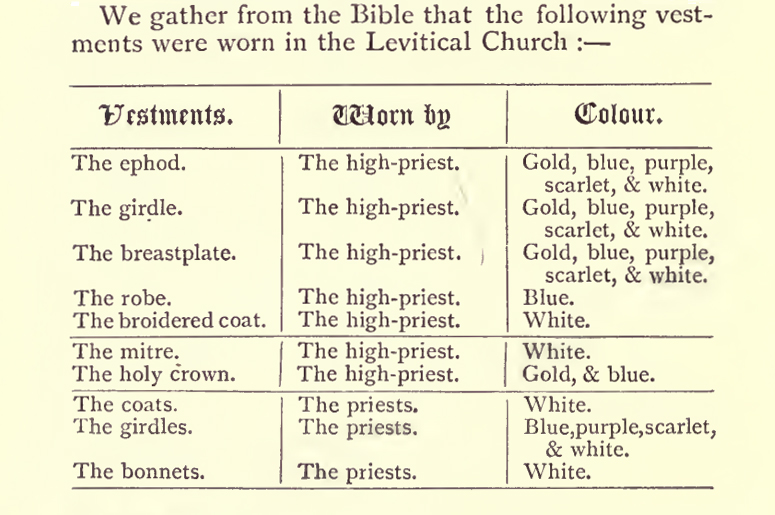

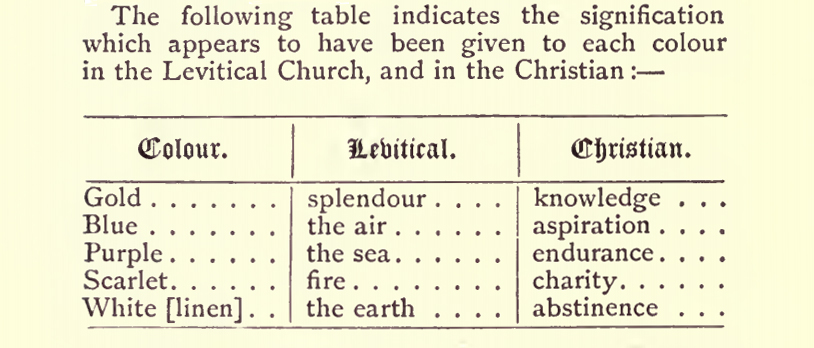

Clapton Crabb Rolfe, in his survey of the history of liturgical colors,

The Ancient Use of Liturgical Colours (1879), used the term "Levitical Church" for the Old Testament symbolism (e.g. on Exodus 28:8 and

passim). He gives two charts which show the general symbolism of the garments and colors that are attested in the early sources:

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/rolfelevitical.jpg

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/rolfelevitical.jpg

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/rolfecomp.jpg

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/rolfecomp.jpg

For example, a writer often cited as the earliest witness to a systematized Ecclesiastical vestment or seasonal color scheme is Giovanni Lotario di Segni (later Pope Innocent III) in

De Sacros Altaris Mysterio (ca. 1195), lib. I. cap. lxv.

Lotario derives his symbolic reading of the liturgical colors from the Bible, Rolfe's "Levitical Church", and makes no reference to the Theological Virtues as such, but does associate wearing red vestments for feasts of martyrs who are also virgins, by referencing John 15:13 in paraphrase (he replaces the word

dilectionem with

charitatem):

Cum autem illius festivitas celebratur, qui simul est et martyr et virgo, martyrium

praefertur virginitati, quia signum est perfectissimae charitatis, iuxta quod Veritas ait: Maiorem

charitatem nemo habet, quam ut animam suam ponat quis pro amicis suis (John 15:13)

Lotario knows green among the vestments, but he assigns them to "weekdays and common days, because green is a middle color between white, black and red. This color is expressed where it is said 'flowering henna and spikenard, spikenard and saffron' (

cypri cum nardo, nardus et crocus (

Cant. 14:13-14)).

Other churches adopted different schemes, and many are discussed in a still useful 1885 paper of John Wickham Legg, "Notes on the History of Liturgical Colours", which first appeared in the

Transactions of the St. Paul's Ecclesiological Society, volume I, pp. 95-134.

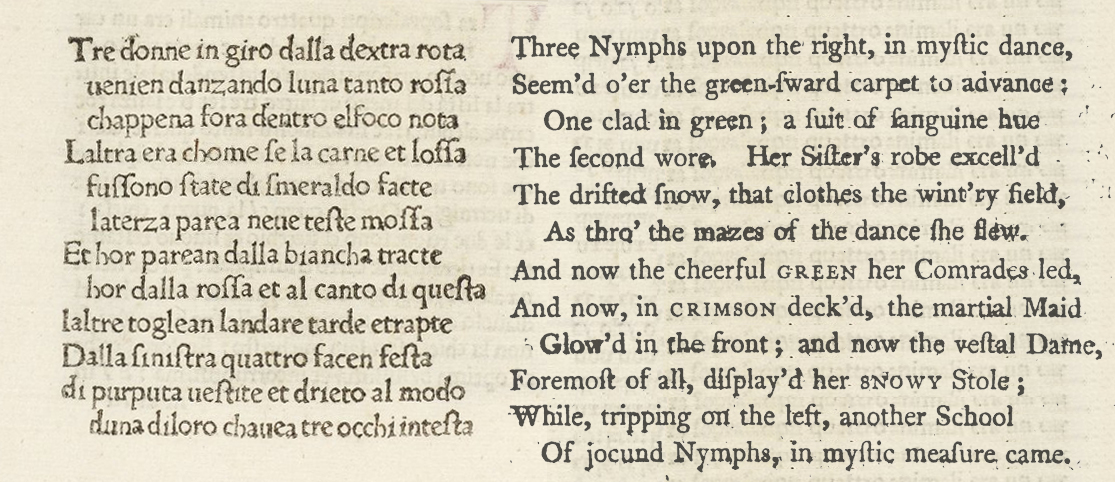

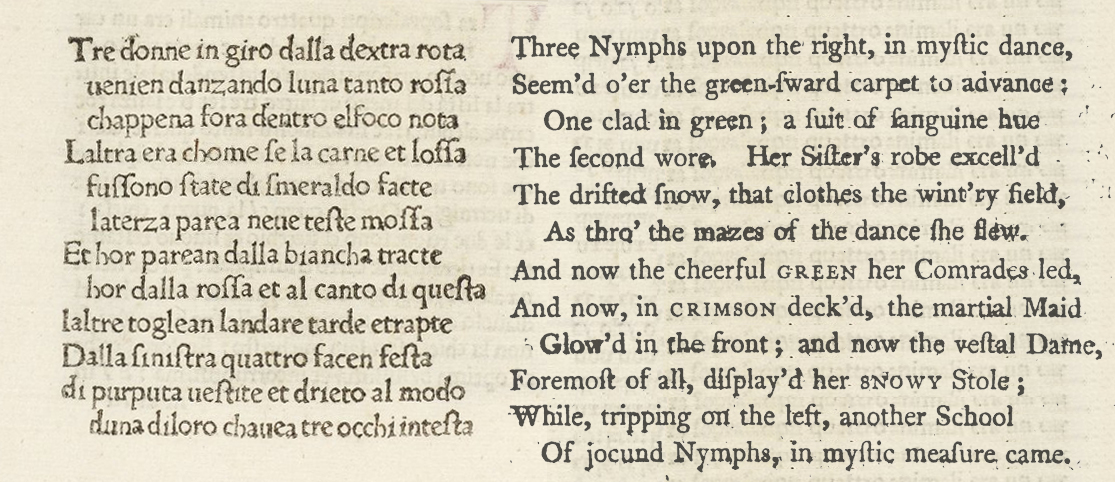

As I summarized above,the earliest direct equation of colors to the Theological Virtues is in the earliest commentator on Dante's Purgatorio, Jacopo della Lana, commenting on

Purg. xxix, 121, at the appearance of the

tre donne in the vision of the chariot:

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/1481b ... ixcomp.jpg

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/1481b ... ixcomp.jpg

(the text on the left is from the first Florentine printing of Dante's

Comedia, 1481; the right text is from the first English translation of the

Purgatorio, Henry Boyd, 1802)

He comments (all of the commentaries on Dante can be found at the Dartmouth Dante Project:

http://dante.dartmouth.edu/ )

Jacopo della Lana (1324-28),

Purgatorio 29.121-126

Cioè

Fides,

Spes et

Charitas, com'è detto. L'una tanto rossa, cioè Charitas. L'altra era, etc., cioè Spes. La terza parea, cioè Fides.

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/1481boyd.jpg

http://www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/1481boyd.jpg

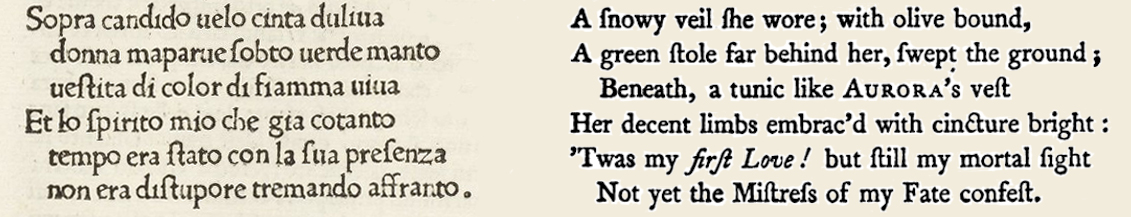

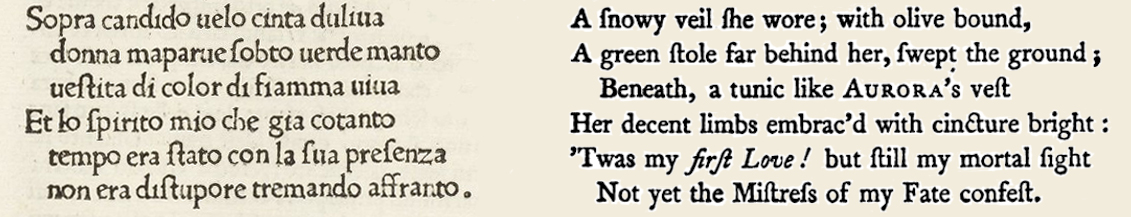

In

Purg. xxx, 31ff. Beatrice appears wearing a red dress, green cloak and white wimple, which Jacopo also read as symbolizing the three Theological Virtues:

Jacopo della Lana (1324-28),

Purgatorio 30.31-33

Dice ch'ella avea sovra lo velo una ghirlanda di foglie d'ulivo, e avea uno manto verde, sotto lo quale stava ammantata, e lo suo vestimento era di colore di fiamma, cioè vermiglio. Lo quale velo hae a significare la candidezza della fede, lo manto verde lo indumento della speranza, la veste rossa la caritade infiammata, la ghirlanda d'ulivo pone per segno che poetriamente s'incoronava a quel tempo di Minerva di foglie d'ulivo. Quasi a dire: io pogno Biatrice per allegorìa essere la scienzia di Teologìa e introducola a tale essere un sermone poetico, e però l'adorno di segni poetici.

So finally to answer Huck's question about colors for the Cardinal Virtues, Dante applies purple to all of them, but distinguishes Prudence with three eyes.

http//

www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/sevenvirtues.jpg

http//

www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/chariot1.jpg

http//

www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/chariot.jpg

http//

www.rosscaldwell.com/dante/dantebeatrice.jpg