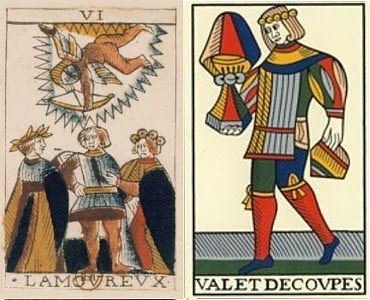

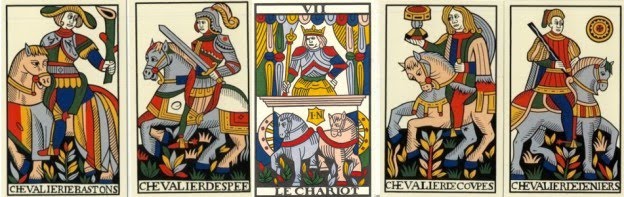

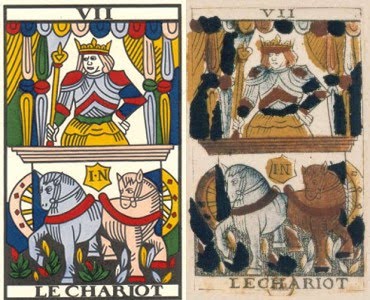

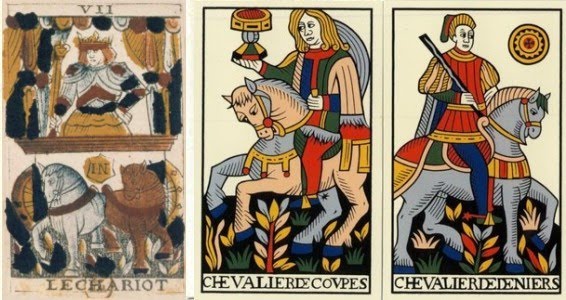

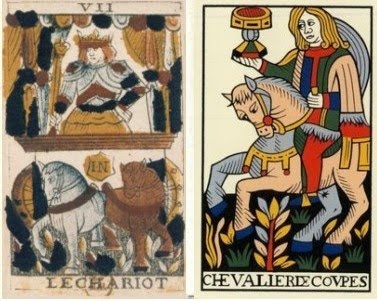

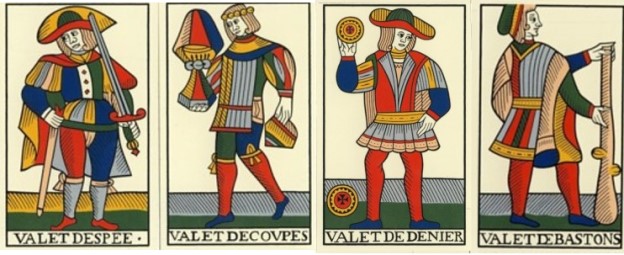

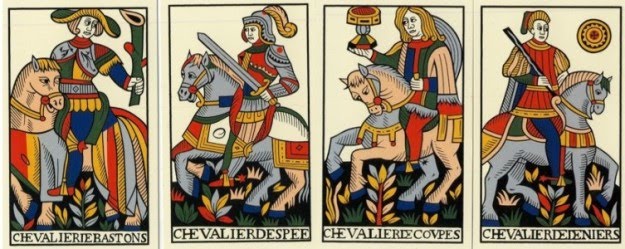

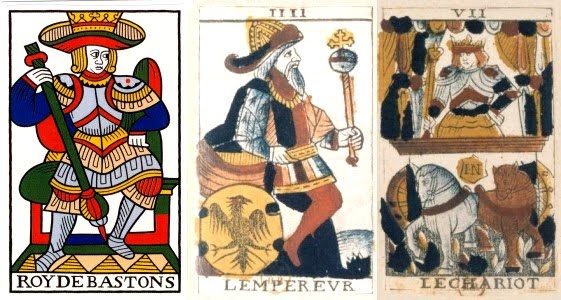

Another schema of interpretation is suggested by visual similarities between aspects of particular courts and particular trumps. From the meaning of the trumps, one can then associate the meaning of the court, and vice versa. For example, the Noblet Page of Cups has a wreath of flowers; and so does the girl on the Lover card (below, left and right). Also, the horses on the Knight cards use the same colors as the horses on the Chariot cards, in four various ways. What do such parallels suggest, if anything?

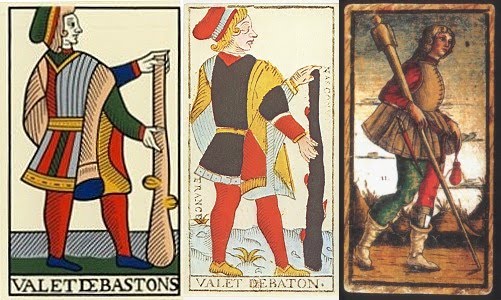

A second mode of interpretation that currently appeals to me is in terms of literary antecedents.Almost as soon as I saw the Noblet Page of Swords (above center), I thought of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. He is standing there lost in thought, perhaps trying to decide something (just as, perhaps, the young man on the Lover card might be trying to decide something). From the way his sword touches his head, it would seem to be something like, “Should I kill myself or my uncle?” or perhaps “Do I really want to be a killer? Maybe I'm not cut out to be a soldier.”

After thinking this, I read Jodorowsky’s account of the pages, where he says (Way of Tarot p. 52).

So at least somebody else has had the same idea.“To be or not to be?” the Page of Swords seems to be asking himself as he prepares to sheathe his sword

On ATF there were a couple of threads a while back on the issue of whether Shakespeare had tarot images in mind when he was writing some of his plays. I am interested in a different question: Is it historically appropriate to see the tarot court cards of 17th century Paris, specifically those of Noblet, in terms of characters in Shakespeare’s plays? Or if not, then those of other plays as known at that time, or of the sources that Shakespeare used?

It is clear that the trumps of the 15th century originated in part from the mystery plays of the late Middle Ages. They also reflected specifically Renaissance expressions of these themes, in art and conceivably also drama. But the court cards were not so definitely defined; they reflected court realities of the time, but in not very interesting ways. As the court cards developed over the centuries, their characterizations improved, especially in the cards of Noblet. Could drama as known in the Renaissance—either Greco-Roman or Renaissance—have influenced how they were drawn and seen?

My thesis is somewhat difficult, I admit. Shakespeare himself, in Noblet’s mid-17th century Paris, was virtually unknown, according to the history books. But French people also went to London, where his plays could still be seen, until Cromwell closed the theatres in 1640, and moreover, there were the first and second folio editions of his works. And after 1640 some theatre troupes may have tried their luck in Paris, catering to an Anglophile crowd. French theatre at that time was rather dismal, except for the much-maligned Corneille, who had been driven out of Paris by Cardinal Richilieu’s Academie Francaise for not following their rules for good theatre. Before 1640, some Parisians would have looked enviously across the channel; after that date, they may have congratulated themselves on their good fortune, if some London actors had come to Paris. It is not necessary that the designer of the Noblet actually have read or seen the plays; he may have just had them described to him and been struck by their intrinsic interest.

My fallback position is that if the court cards do not reflect Shakespeare, then they at least reflect characters from which he drew his unique creations. It is well known that he rewrote stories from other sources—Greek, Latin, Italian or French. Some of these sources were well regarded in Paris: e.g. Plutarch’s Lives and Seneca. In some cases I have found the relevant characters in his sources; in many cases I have not. This is especially true of the one play whose influence I see most often in the Noblet: Hamlet. Hamlet himself is the first of his kind, as far as I can tell.

(Note added by mikeh Jan. 10, 2011: In fact, 16th century French sources can be found for Shakespeare characters corresponding to all the Noblet courts. They, in turn, have 14th-16th century Italian sources. These in turn have characters corresponding to them in Latin and Greek classics well known during this whole era. So it is possible to read my argument without Shakespeare entering in at all. I refer those who wish to read this argument, in which Shakespeare drops out, are referred to my final consecutive post in this series, entitled "additions, summary and alternate hypothesis," of Dec. 15, 2010.)

HOW WERE THE SUITS DIFFERENTIATED HISTORICALLY?

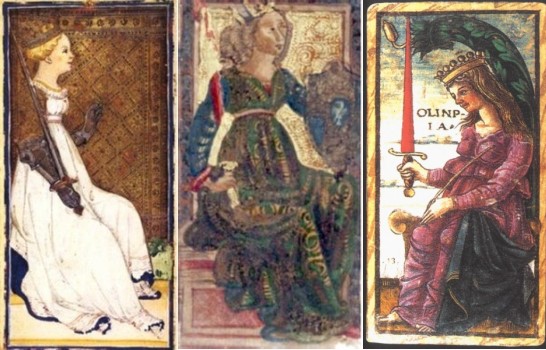

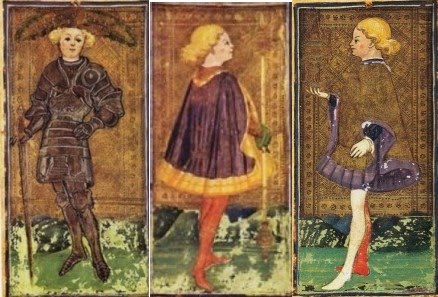

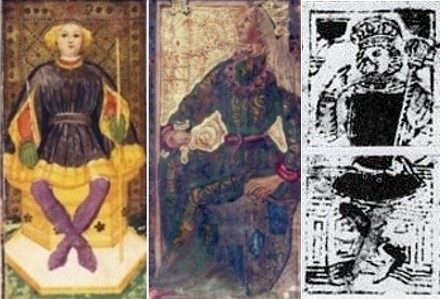

Court cards obviously had a life before Shakespeare. Earlier interpretations would have continued, the Shakespeare-types merely grafted onto existing stock. So I should probably say something about those earlier cards.

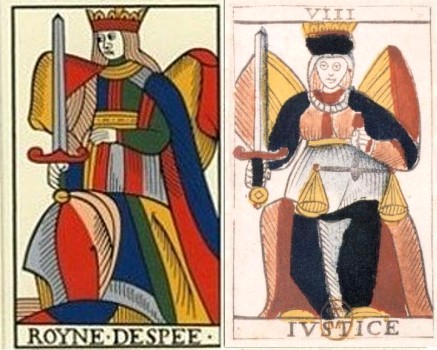

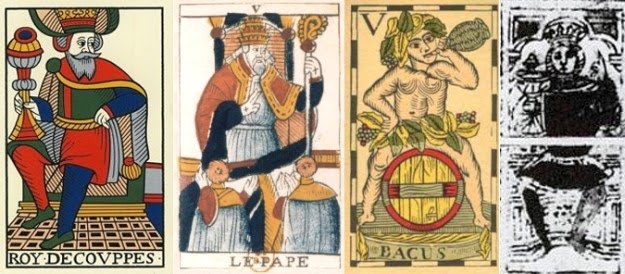

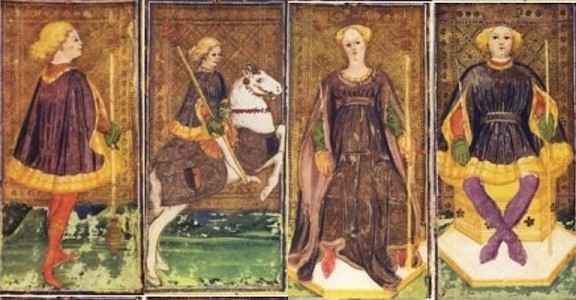

Looking at the early courts, it is clear that there is some meaning to the differentiation among suits. Swords not only carry their suit sign but wear armor. In one 16th century Italian-style deck, which may or may not be a tarot (Kaplan vol. 2 p. 277), the King looks at the viewer as though holding his subjects accountable for something, lest they taste his sword. (Perhaps he is even pointing at us; next to him, Cups is pointing upward, and Batons at himself.) For their part, Batons not only wield batons, as a symbol of authority or as a modest weapon, less effective than a sword, but sometimes have other differentiating features. In the PMB they all have green sleeves or gloves, signifying agriculture or fertility.

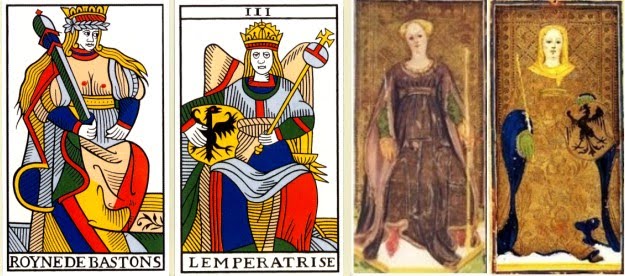

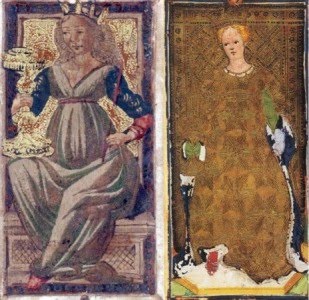

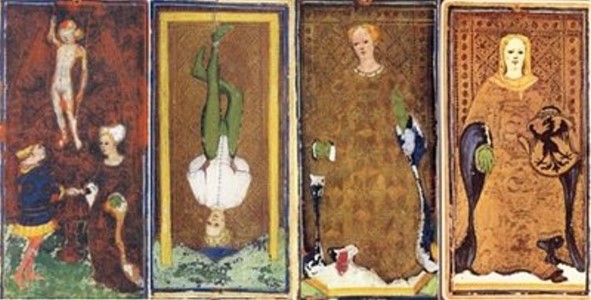

I base my interpretation not only on the traditional association of Batons with agriculture, but on the same green garments’ appearance in four other cards: Love, Hanged Man (for the resurrection), Queen of Cups, and Empress.

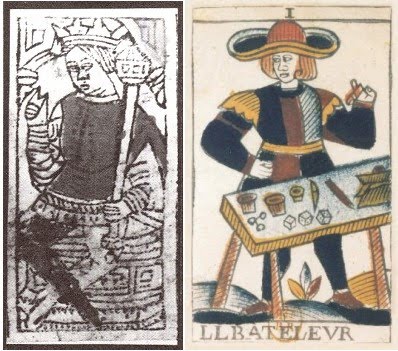

In the 16th century deck that I posted above, as I have said, the King of Batons points to himself; perhaps he means to be pointing to a prime source of fertility. In another 16th century deck (Kaplan vol. 2 p. 184), the King of Batons has a phallic finger, which we might recognize from the Noblet Bateleur.

Coins on the cards, which the court figures display, are made in the likeness of coins, suggesting a dealer in money, such as a banker or a merchant. In cups, the Ace of Cups often looks like a baptismal font, and the cups themselves could be communion cups. Similarly, the King in the 16th century deck I showed first (also bottom row below) points toward heaven. But the same deck shows a Page downing a drink.

In the 18th century, several writers made observations similar to those I have just made. De Mellet, for example, says (http://www.donaldtyson.com/gebelin.html):

Also:

But there are a couple of problems. First, meanings got attached to the comparable suits in regular cards based on how they looked: e.g. love with Hearts. That probably had an effect on the similar suit in tarot, emphasizing the relationship of Cups to love as opposed to religion. Second, the suits may have evolved new meanings on their own. In the 19th century we hear of Swords as about thinking, Cups as about the emotional life, Coins about health, and Batons as about access to magical realms. Were these changes introduced by the Golden Dawn, or were they continuing a tradition already in effect, perhaps even before de Mellet? Just because de Mellet didn’t mention these meanings doesn’t mean they didn’t exist. His acquaintance with the cards was probably superficial.

There is also the question of to what extent there was competition from other principles of card design, e.g., the four temperaments. Part of the problem here is deciding which suit goes with which temperament. Sources from that time do not agree.

Then there is the question of how to interpret the different ranks, from page to king. The Sola-Busca tarot deck of 1491 shows evidence of Neopythagorean influence in the pips and of an arrangement according to the four temperaments in the courts. The Noblet trumps, I think, show Neopythagorean considerations as well (viewtopic.php?f=12&t=530&start=20#p8518). Well, the same Neopythagorean structure could have been applied to the Courts. Jodorowsky has developed this theme, although his assigning the highest value to the Knights is obviously without historical merit. What follows is my own, based on the Neopythagorean precepts I discussed in the thread "Deciphering the Sola-Busca Trumps" for the Aces through Fours (starting at viewtopic.php?f=12&t=530) and Pages (11) through Kings (14) (starting at viewtopic.php?f=12&t=530&start=40#p8973).

The Pages correspond to the Monad, the beginnings, a young man just starting out, in any of four different directions. There might be a relationship to the Bateleur and to Strength, trumps numbers 1 and 11. The Knight is the journeyman in that profession. Since the Twos involve separation from the One, becoming a journeyman requires some separation from the former master, perhaps even moving to another town. Pages are unmarried; Knights might be, but if married, it is secondary. He is primarily on a quest to prove himself. Knights, as Twelves, might have some relationship with the Popess and the Hanged Man. The King is the new Master, who has made a success of himself. His number, Fourteen, is also the Four, the Tetrad, which represents full realization (as in the four directions, four elements, or four gospels). He is related to the Emperor, and perhaps in some way to Temperance (the mean between extremes?). The Queen is the Master’s wife and helper, who also might assume the duties of the Master if he dies or is away, either formally or actually. Her number, Thirteen, is also the Three, a number associated with child-bearing. It is related also to the Empress and perhaps to the Death card.

ENTER SHAKESPEARE

Let me give an example of stock characters that I do not see in the court cards: namely, those of Commedia dell’Arte. There were for example Pierrot as the frustrated lover, Pantalone as the wealthy elder suitor, and Columbine as the young lady being courted by both. I don’t see any of this in the cards, even in the Lover. I admit that I don’t know Renaissance Italian drama very well; but when I do read about it, I don’t see how it could generate the Courts. Yet from Shakespeare, who was only a few decades earlier than the Noblet, I can generate characterizations of many specific Noblet courts, as I will demonstrate in subsequent posts.

In one place Shakespeare gives a list of seven stock characters, described in rather satirical terms: the “seven ages of man” speech in As You Like It,. One of the characters, the melancholy Jaques, recites it to the audience. It has no relationship to the action of the play; so it could easily have been known by people not at all familiar with Shakespeare. It begins:

The list of satirical characterizations that follows correlates to the seven planets, from the Moon to Saturn, as well as to the traditional seven "ages," from "infantus" to "decrepitas." I have found the individual characterizations corresponding to age and planet of some use in describing the Noblet. I will quote them in the appropriate place.

Besides these schematic characterizations, there are also specific characters in the plays themselves. Certain figures in the Noblet courts correspond to certain characters in the works of Shakespeare. The majority are in just one play, Hamlet. I will give an example in my next post.