Metropolitan Museum

http://www.metmuseum.org/works_of_art/c ... 32526&vT=1

Trionfi version

A nice example, how bad the Trionfi.com pictures are, but it should be the same engraving. The dating of the Metropolitan edition is probably made according the general estimations about the Mantegna Tarocchi, so "according Hind".

Variations in the letters might depend on the bad pictures, even the size of the letters is no guarantee, as the Mantegna Tarocchi designer might have used different letter stamps.

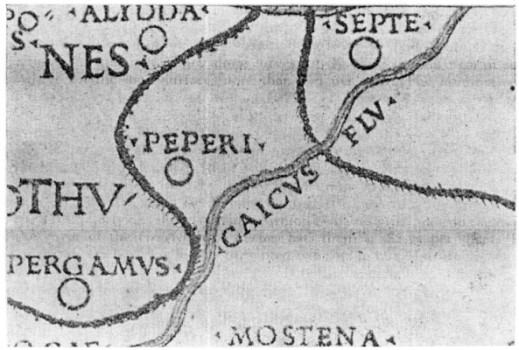

The suggestion, that the engraver of the Ptolemy edition and of the Mantegna series is the same, was made by Hind, not by me. Hind surely had better material to observe.

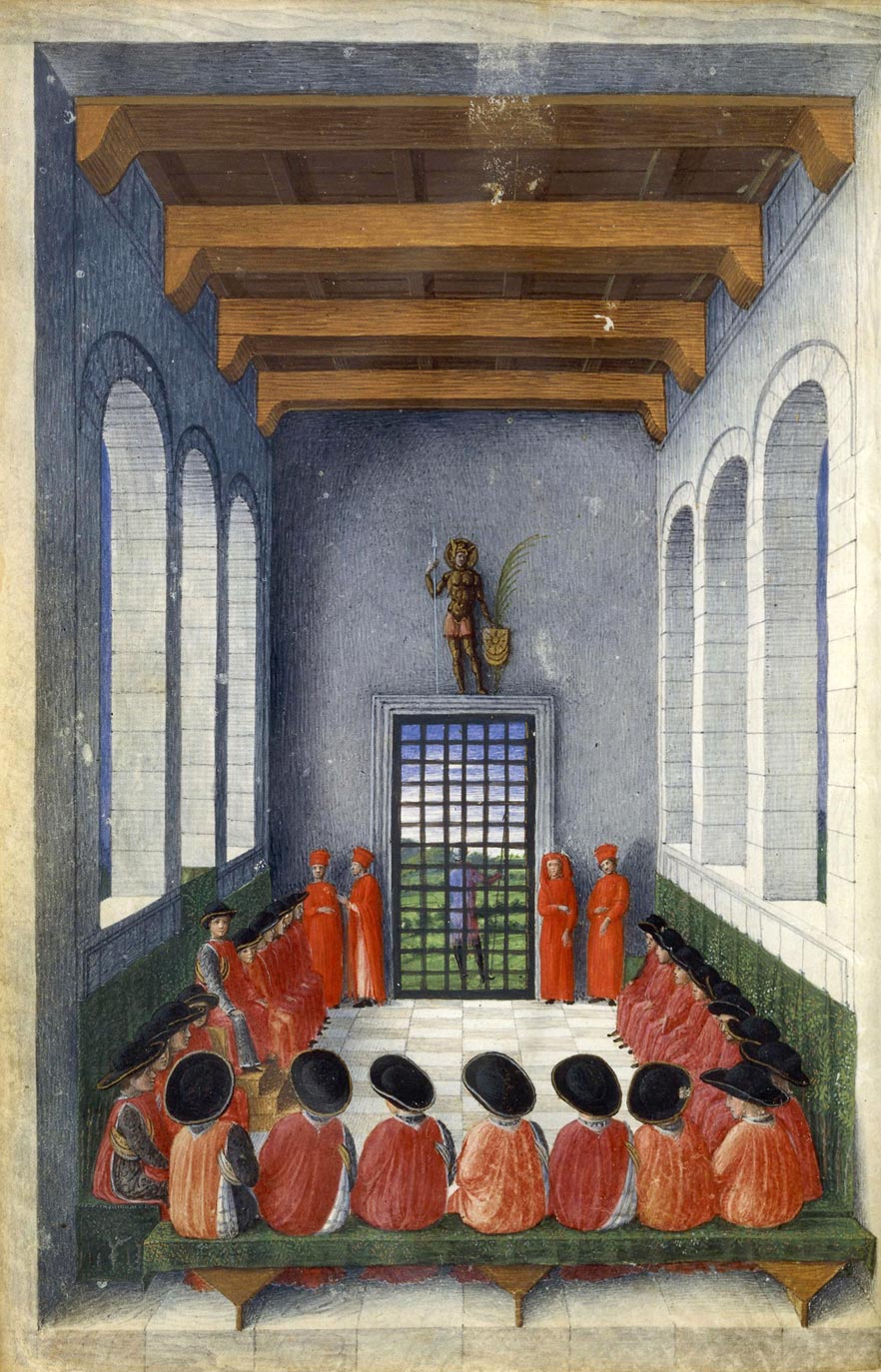

I don't know, from which source you do have this wisdom. I recognize from this composition, that "Poesia" (Mantegna Tarocchi) reads "Poesis" in the Lazzarelli version (as far this is recognizable; Lazzarelli's is the small picture in the right upper corner).mikeh wrote: The Lazarelli manuscript has the names of the images in Venetian dialect already.

When Ferrarese artists emigrated for better working conditions to Bologna, they somehow would stay Ferrarese artists ... With the plan of Leonello (ca. 1446) for a Studiolo a general Ferrarese interest in "Muses" was given in Ferrara. As far we can guess it, it was for some time specific for Ferrara and not a general feature of Italian art. During this project a lot of "Muses-versions" might have been developed, just as preparations of the final big versions, maybe as small ink paintings, which as a pool stranded in Venetian art and printing shops as "cheap art" ... generally it should be calculated, that Lazzarelli likely wasn't very rich, so he couldn't buy very expensive pictures.Well, I gave several reasons for preferring Bologna as the place of origin for the designs and perhaps also the engravings. I wrote, "For Bologna, I offer (a) Galasso's move there, as the most likely candidate for the "anonymous Ferrarese" whose style is closest to the cards; (b) the marked divergence of the "Mantegna" from Borso's (as opposed to Leonello's) Belfiore Muses and most of the Schifanoia; (c) the presence there of the 1467 miniature, (d) the keys of the Pope card as Nicholas V's device [Bologna's favorite Pope, let me add], and possibly (e) the resemblance in engraving technique to Florentine engravings of the time [Bologna's ally] and (f) the later presence there of the Belfiore Euterpe and Melpemone. Moreover (g), Bologna, with its internecine feuds, suffered from too much passion and intensity; the elevated but conventional mood of the cards, in contrast to the best of Ferrarese art, would have been welcome there."I don't know, what's so interesting in Bologna.

But none of these arguments are strong. The 3 Muses were in Ferrara, where anybody with access to Borso's studiola could copy them, design engravings, and keep going, despite their incompatibility with the more fashionable styles of Tura and del Cossa. The cardmaker Gherardo da Vicenza, whom Campbell (1997) says did a lot of repetitive house decorations, could have been just such a designer. And the cards once printed could have gotten to Bologna easily enough. So I have to say Bologna is most probable, followed by Ferrara.

For his own paintings, which appear in the manuscripts, he had an own "Apelles", as he remarked in his text.

If Lazzarelli had taken a well known version, which had appeared as a complete version of 50 pictures in large numbers before, for his manuscript, how cheap would that have looked in a manuscript for duke Borso or the duke of Urbino? Especially for Montefeltro it is known, that he took a conservative position against printed, "mass-produced" media. Montefeltro accepted Lazzarelli's version ... an indication, that the Mantegna Tarocchi as a whole didn't exist.

More than one Ferrarese artist went to Bologna. The 1467 manuscript is from there and this makes 2 1/2 not very precise motifs of 50, which is somehow less than 5%, so not very much. The St. Gallen manuscript has 4 motifs, more or less totally precise (so a direct link to the engraver), 8% of the motifs. Lazzarelli reaches more than 50% of the motifs, though only illustrations.Huck wrote,My alternative, Bologna, is not one possibility equal to a universe of others. II have (a) Galasso's reported move there; (b) the 1467 manuscript; (c) German printers in town and nearby Benedictine monasteries, to account for the 1468 manuscript; and (d) the close association of Bologna and Florence, the center then of North Italian engraving. And other reasons already listed above.Sweynheim entered the discussion, cause Hind believed, that the engraver of the Ptolemy edition of 1478 might have been the engraver of the e-series ...

There are many alternatives, a whole universe of alternatives, but Sweynheim was "recognized" as a possible candidate by Hind.

...

..And about the hot-bed of gambling in Bologna: We know the few documents and we probably know them better than Hind did. And "gambling" mostly means dice, not playing cards or woodcut use

Benedectine monasteries ... you haven't offer any. I've offered a few opportunities to search, but I haven't offered a monastery, which fulfills the demanded conditions. You've offered a shot in the blue, nothing else.

Bologna developed printing technologies ... since when? What is the first engraver in Bologna? What about a person with the name Francia, who is reported as having worked as a goldsmith since 1468?

San Bernardino preached at many locations, not only in Bologna. The whole story about San Bernardino and the card maker ... ask Ross.

Didn't he say 1423?He also says, "it needed St. Bernardino in his lenten sermons in this city in 1424 to persuade the players to burn their cards."

Not IHS?"Whereupon the preacher, taking a compass at hand, described a circle on a tablet, in the center of which he drew the H.T.I. surrounded by rays."

And what about this, from Hind, previous page?Kristeller notes...a card-maker (pittor di niabi) of Florence, Antonio di Giovanni di Ser Francesco, who declares amongst his property in 1430 'wood-blocks for playing-cards and saints.'

As we know, Florence was a city full of artists, in aspect probably better than any other city.

One engraver or woodcutter in 1430 till ca. 1450 is a very bad result, either based on "careless research" (which isn't the case ... nothing is better researched than Florence) or based on negative reality ... there wasn't much engraving in Florence. Likely this depends on the many card prohibitions in Florence.

http://trionfi.com/0/p/20/

8 card producers in Nurremberg till 1450 ... surely also a city full of artists.

No, he also visited libraries in Italy. But I'm not here to defend Hind, surely he was limited by the conditions of his time ... although we've to state that Hind already presented the major arguments, we have to deal with in the case of the Mantegna Tarocchi. And we discovered Hind's note about the connection to the engraver of the Ptolemy only, when we studied Hind's text, not by referring notes of later writers. So it's (possibly) a case, that others didn't read Hind carefully enough.Huck wroteHind based his book on what was in the British Museum.I've seen Hind's collection about early Italian engraving and wasn't so much impressed. Engraving catalogs of German and Flemish engravers offer much more. But I'm not a specialist.

About Lambert and her work I don't know, I can't judge it.

About Blockbücher ...

http://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/index ... rdnung=sigBlockbücher sind im 15. Jahrhundert im Holzschnittverfahren hergestellte illustrierte Bücher relativ geringen Umfangs, die eine Übergangsform zwischen der illuminierten Handschrift und dem illustrierten gedruckten Buch darstellen. Sie gehören zum seltensten und damit wertvollsten Sammlungsgut von Bibliotheken. Weltweit sind nurmehr etwa 100 Ausgaben von 33 verschiedenen Werken in etwa 600 Exemplaren nachweisbar.

[/quote]Als Heimat der Blockbücher gelten die Niederlande und der Oberrhein (Basel, vielleicht auch Straßburg). Sie ist zu sehen im Zusammenhang mit den sonstigen Bemühungen des 15. Jahrhunderts, Bücher möglichst rationell und preiswert herzustellen.

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blockbuch

Examples

http://www.hab.de/bibliothek/wdb/xylographica.htm

A complete full-page-technology, which was probably only used in the Netherlands and in Germany - before it was overcome by Gutenberg's letter printings.

Maybe something, which Baldini attempted in Italy with full page engravings - as you've mentioned for 1460-64.

*********

Jenson had been in Mainz, so he knew Sweynheim from there. He's not recorded for Subiaco or Rome. Ulricus Han is said to have been also in Subiaco, and he printed in Rome. A not very clear role plays the cardinal Torquemada, who was "Abbot commendatario of the monastery of Subiaco, August 13, 1455", who invited possibly Ulricus Han and also Sweynheim and Pannartz.

http://www.fiu.edu/~mirandas/bios1439.htm#Torquemada

Perhaps he's only involved, because he was just the "abbot in function" for Subiaco, perhaps it was so, that also Spain had some more experience with printing technology than the general Italy and Torquemada (and Subiaco) was chosen cause of this reason. The first printed book in Rome had been "Meditationes seu contemplationes vitae Christi" (1466), written by Torquemada himself.

Though ... it seems probable, that Subiaco was chosen, cause Benedectine abbeys had been full of Germans.

The motor of getting German printers to Italy should have been Pope Pius II. and Cusanus, both experienced with German conditions and both dying in 1464. So Torquemada got the responsibility.

****

...

For the dating of the Baldini pictures, see ..

viewtopic.php?f=11&p=6033#p6033