Niccolo Tedesco or Nicolaus Laurentii, Alemanus

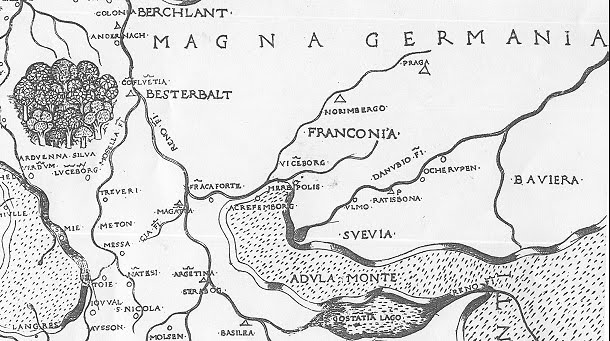

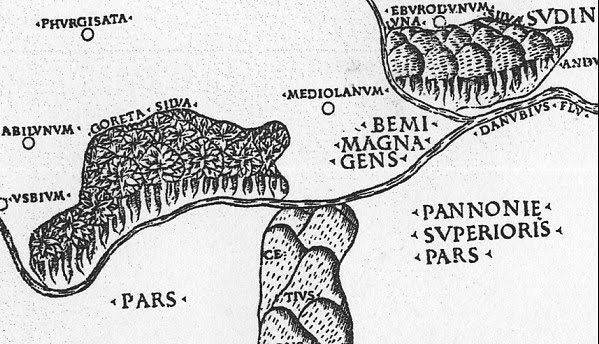

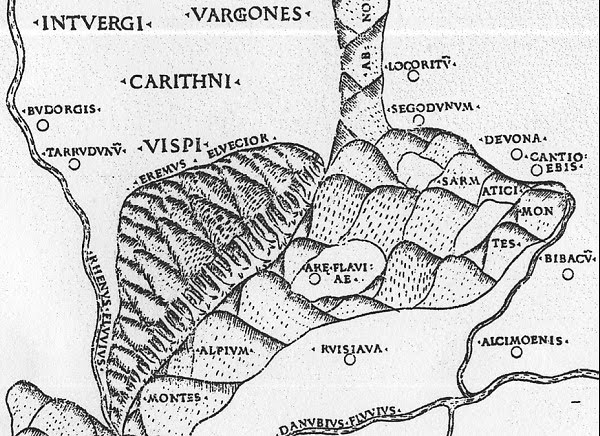

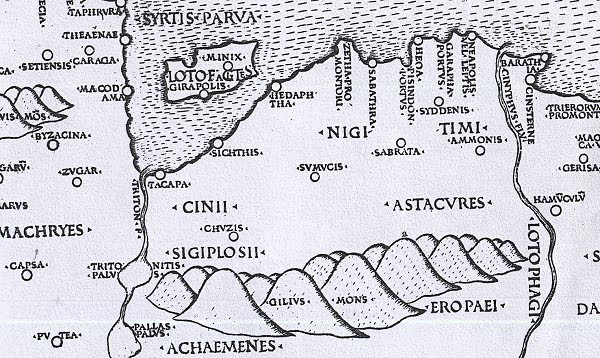

worked as printer in Florence 1474 - 1485 and combined copperplate with printing, made the Berlinghieri map for Francesco Berlinghieri (1482), this called a friend of Lorenzo and son of a merchant, who had a lifelong cooperation with the Medici, but died in 1480. As the business wasn't finished correctly, Lorenzo de Medici sued the children of the merchant in 1486.

Niccolo Laurentii Tedesco is said to have been from Breslau, which has quite a distance to Reichenbach, where the other Nicolaus Germanus had been monk in a Benedectine abbey.

But: Nicolaus Alemanus in 1464 in Florence (mentioned by Durand) ... this might fit. This made "Tabulae etc." of 12 houses, and as I got it, it appeared in ...

http://books.google.com/books?id=bXAxRO ... 22&f=false

... together with some other writing, also from Cusanus.

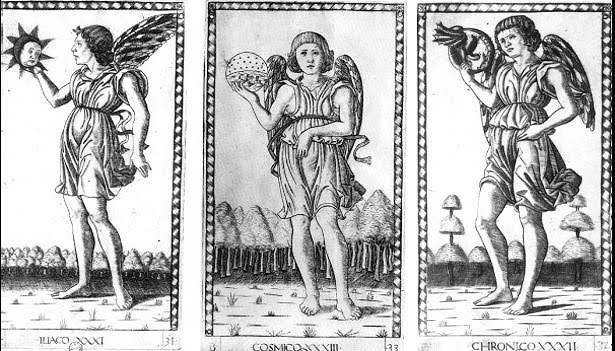

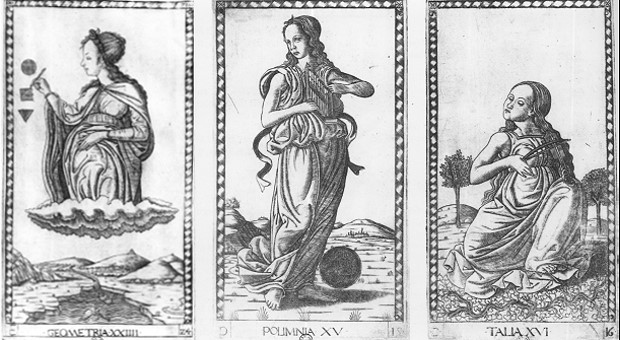

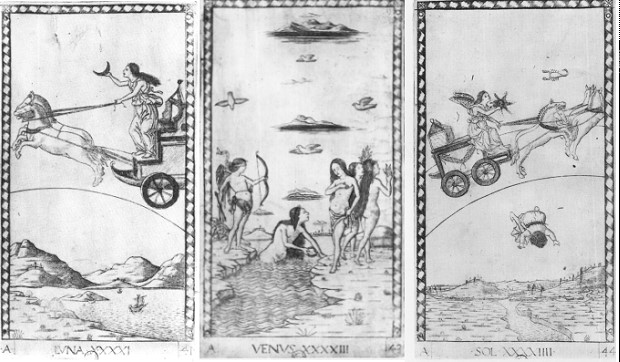

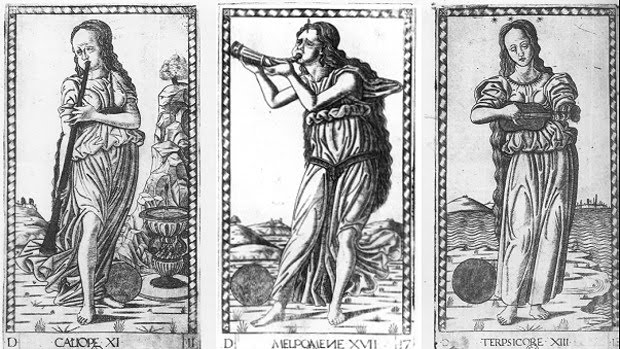

Whereby I start to think about the coincidence of Nicolaus in Florence and the appearance of 12 planet gods (calendar with "good" engravings, recently discussed in Finiguerra context) in the same year 1464. Difficult to estimate in the current state, what these tabulae were.

His start as a printer is remarked as "1477", but I found this:

http://istc.bl.uk/search/search.html?op ... rowse=true

... which speaks of end of 1474 / begin of 1475

I was puzzled by a note which told, that the Crivelli 1477 edition in its opening noted a "1462" ... which actually might be the date of the work of Nicolaus Germanus.

Also there is some talking, that a "traitor" went from the Sweynheim team to the Crivelli team in Bologna. This might well have been Nicolaus Germanus, which got a considerable sum from Sixtus in 1477 for his two globes, before the Ptolemy edition of Sweynheim/Bucking appeared.

From Nicolaus Germanus it is told, that he "disappeared" after 1477, although he participated somehow in the German edition of 1482 (Johann Schnitzer in Ulm). From Nicolaus Laurentii, Alemanus it is told, that he "appeared" 1477, although he already was there 1474/75, if we can trust this dating.

The "disappearance" of 1477 has some political logic, when we assume, that Germanus really had a relation to better circles of Florence (as we may assume from his printings) - the assassination of Giuliano de Medici took place April 1478 and after this had been bad times between Florence and pope Sixtus. And Nicolaus Germanus possibly had reason not to appear with this name by which he was known in Rome.

Nicolaus Germanus ... Benedectine monk, made globes and atlasses, somehow related to Florence

Nicolaus Laurentii, Alemanus ... made (or "it's said, that he made") the Berlinghieri maps, related to Florence

Sweynheim & Pannartz ... worked first in Benedectine abbey, produced Ptolemy maps

All related to maps. Possibly Nicolaus Germanus and Nicolaus Laurentii, Alemanus are the same person?

Astronomy he learned in Reichenbach. Engraving and printing he might have learnt from Sweynheim & Pannartz.

In the wiki he is said to have worked with Johannes Petri from Mainz in a nunnery ... this should have happened 1476 in Florence, as I see from this source:

http://www.gizapyramids.org/pdf%20libra ... 62to64.pdf

The installation of the Ripoli printing press shouldn't have taken too much energy - perhaps a document was only interpreted as his first appearance. But, see above, he was already active in Florence before.

Well, I don't know ... 2 pages in the Durand online text are not readable. Perhaps there's further material.

**********

!!!!!

"John of Kulmbach", the alchemist, mentioned in the Durand article, who invited an "obscure" Italian humanist Arriginus, is actually Johannes of Brandenburg, the father of Barbara of Brandenburg, wife of Ludovico Gonzaga (who arranged the congress of Mantova 1459, the same, from which Brockhaus assumed, that there the Mantegna Tarocchi was invented).

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_%28 ... ulmbach%29

Compare also: Printing press in Ferrara

http://trionfi.com/0/p/04/

Well, there are these 2 missing pages. But the person mentioned is this here, Matthias of Kemnat:

http://www.mrfh.de/uebersetzer.php?tran ... &bio_id=24

He had close letter contact with Peter Luder, who had studied in Ferrara under Guarino and with Leonello (probably the only German there in this early time), just at the time, when the Trionfi cards appeared (since around 1440 till maximal 1445, then he is recorded in Venice). Kemnat should have become acquainted to him in Heidelberg ca. 1456-58.

Kenat was friend of Wimpheling, who became the foe of Thomas Murner much later in Strasbourg.

So we have an astonishing close way for the astronomer monk Nicolaus in 1456 to Borso in 1466. Nicolaus knew Kemnat, Kemnat knew Luder, Luder knew Borso.

*****************

Borso 1466 asked an astrologer, if Nicolaus' work is worth the money. The name of the astrologer appears as "Pietro Bono Avogaro". This is mentioned here ...

http://books.google.com/books?id=QfYiWv ... ro&f=false

... he participated in the Crivelli edition together with Girolamo Manfredi - Galeotto Marzio - Cola Montane (!!! who was involved in the murder of Galeazzo Maria) (at another place called Cola Martino ? typo ?) and worked as astrologer for Borso and Ludovico Sforza.

Well, a rather strange story ... read yourself. Another source notes also "perhaps Filippo Beroaldo".

Avogaro (Ferrara) is also noted as a medical doctor, Girolamo Manfredi (Ferrara/Bologna) as another astrologer. Galeotto Marzio (Ferrara, Bologna, Padova, Hungary) worked as humanist, physician and astronomer, also for Matthias Corvinus in Hungary. He was in prison in Venice and a book of him was burnt. Filippo Beroaldo (Bologna, Paris) was a writer. Cola Montane is well known as a teacher of rhetoric in Milan, who hated Galeazzo and arranged his murder. Galeotto hated Filelfo and another Milanese humanist.

Avogaro and Manfredi are said to have predicted the murder of Galeazzo. Galeazzo didn't love that.

Nicolaus Germanus isn't mentioned.

*********

http://www.mapforum.com/02/ptolemy.htm#rome

Here a new name appears, "Nicolo di Guggio", a person, who otherwise not exists in the web. ???? Wrong reading of "Nicolaus Germanus" ????Based on Jacobo d'Angelo's translation of Ptolemy's text, which was proofed by Pietro Bono and Girolamo Manfredi, and then corrected by Galleoto Marzio and Nicolo di Guggio, with a final revision carried out by Filippo Beroaldo; the maps were compiled by Bono and Manfredi, and drawn by Taddeo Crivelli.

*********

I found this:

http://books.google.com/books?id=jBcAAA ... is&f=false

I found the remark of the printer interesting.