The Devil is an interesting figure in terms of the Dummett's 3 Segments, Shephard's Three Worlds, or my own 6/9/7 model. In that regard, the first noteworthy aspect of your posts is that you reject Dummett, Shephard, and my own analysis, and put the Devil with the allegorical section rather than the biblical/eschatological section. If the sequence is taken to be meaningful, then this makes him an allegory of Sin, (common in period works), or the Prince of This World, or... something else appropriate to the middle section. I'll elaborate on that some. On the other hand, you also seem to reject that the sequence is meaningful, getting closer and closer to the agnostic dismissal of iconography which Dummett maintained. I'll defend the idea of the Tarot trump cycle, at least in some decks, as a meaningful iconographic programme, that this was important for learning the hierarchy as well as enjoying the game, and that we can approach an understanding of that programme by focusing on what I've called affine groups.

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAILS (NUGGETS? AFFINE GROUPS?)

My first response is, huh? You reject the connection between Devil and Fire/Tower because it is too forcefully explicit? And you reject the idea that something so forcefully explicit would be easily remembered? It seems to me that a dramatically clear pairing, especially one depicting a central incident from Revelation, would be as memorable as anything imaginable and therefore a perfect subject to be easily remembered, in context.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:The first step came with my growing discomfort with the force of that particular "narrative nugget" in an otherwise less than catechetically clear section. Why such an explicit appeal to high and serious religiosity in a set of pieces only designed to be easily remembered in sections? Where does it go now? To a Star - is this a symbolic reference to Jesus? But then who are the Moon and the Sun, etc? It just didn't make sense that the designer would be so explicit here but so allusive in the rest.

You seem to be arguing that this bit of the cycle is TOO clearly represented, so we must reject it. Is this really an approach that you want to defend? I would argue that it is a traditional occultist methodology when faced with anything obvious -- reject it and impose something less plausible but more congenial to our interests. The Wheel of Fortune is too obvious, so it must be a secret allusion to the wheels of Ezekiel's vision, etc. Robert O'Neill explicitly defended this sort of rejection of the obvious. If we accept that approach, then Judgment and the New World are also too clear to be accepted. Likewise the three signs in the heavens, between these other eschatological elements, are just too readily appropriate and easily understood. Therefore, they can't be taken at face value, in the context of Rev. 20 and 21.

There are actually three narrative "nuggets" in the highest section. They are closely related and extremely prominent subjects: they emphasize the two great triumphs of God, over the Devil and Death, at the time of the Second Coming. The designer was forcefully explicit in each part, if you can remember the whole while analyzing the parts.

The term Hermeneutic Circle comes to mind. "It refers to the idea that one's understanding of the text as a whole is established by reference to the individual parts and one's understanding of each individual part by reference to the whole. Neither the whole text nor any individual part can be understood without reference to one another, and hence, it is a circle." The circle metaphor is weak, as it suggests circular reasoning or going around in circles, meaning that no progress is being made. In fact, is an iterative process which tends to yield better approximations, progressively converging toward a best reading. (The weasel words, "tends to", admit the possibility of more than one good reading, or none at all. Even the best path can't take you to a place that doesn't exist.)

As noted at the top of the previous post, we agree on the fact that Tarot was a game, designed as a game and popularized as a game, and that this has some important implications. You seem to be using this, however, as an argument that the trump cycle was therefore not well designed as an iconographic programme. IMO, these narrative nuggets are not only what explains the original choice of subject matter and sequence, they are also what the designer had in mind as a mnemonic device to teach the game and make the hierarchy readily understandable. Meaning is memorable. A detailed iconographic program is what makes the design good for a game. The more structure is apparent, the more mnemonic the design was intended to be and the more easily the order can be explained/taught.

The highest trumps represent the End Times, with the triumph over the Devil, the signa coeli, and resurrection to the New World. That's just 22 words, and short enough for a tweet. That single sentence would constitute a completely sufficient explanation of the highest trumps and their order to anyone of that milieu. Voila! Twenty-two words and you've just learned the order of the highest trumps. Look at the subjects, and you know their relative placement, because you already know the constituent elements. It's that quick and easy, precisely because of those three affine groups, aka nuggets, within that eschatological section.

You seem to argue that one part of it is too clear to accept, and the other two parts are too obscure to accept -- is that right?

Narrative: Deliver us from evil. (Cf. the Lord's Prayer.)

Cards: Devil and Fire from Heaven.

Order: Fire from Heaven trumps the Devil.

Prooftext: Revelation 20:7-9

Narrative: Signs of the Second Advent.

Cards: Star and Moon and Sun.

Order: Increasing light; an obvious mnemonic.

Prooftext: Luke 21:7,25 And they asked him, saying: Master, when shall these things be? and what shall be the sign when they shall begin to come to pass? [...] And there shall be signs in the sun, and in the moon, and in the stars; and upon the earth distress of nations....

Narrative: Thy kingdom come. (Cf. the Lord's Prayer.)

Cards: Angel of Resurrection and New World.

Order: Revelation 20 comes before Revelation 21

Prooftext: Rev 20:12-13 and Rev 21:1

To me, all three parts are equally clear, and it is a very neatly designed section of the trump cycle. Forcefully explicit nuggets are also apparent in the design of the middle trumps, in either the Bolognese or Milanese (Tarot de Marseille) orderings. (This bleeping site expands Tarot de Marseille into Tarot de Marseilles. Otherwise, it could also represent the precursor, Trionfi da Milano.) The subjects follow a universally known narrative, and are neatly grouped within that larger narrative. Just to make the point that it's trivially simple, another 22 word summary: The middle trumps narrate Fortune's Wheel: success (Love/Chariot), reversal (Asceticism or Time/Fortune), and downfall (Traitor/Death), responded to with Virtue. This one's a bit long for a tweet, but it's still pretty simple. The design itself, groups of 2 or 3 related subjects in a narrative arc which form a complete schematic arrangement, a complete "thought", is the same sort of thing that we see in the highest trumps. This makes it look VERY much as if we have found the structural pattern of the designer.

How/why would this happen? Imagine that we are creating a game of triumphs in 1430s Italy. For the highest triumphs we want to show the two great eschatological triumphs of Christ, over Satan and over the last enemy (Cor 15), Death. What could be more exalted or appropriate for a game of triumphs? So we choose Rev 20:7-9 and select a Devil and Fire from Heaven as two cards to represent the first triumph. Rev 20:12-13 resurrects the dead, and Rev 21 is the reward, glory, triumph over Death. We want a few more cards for this section, with recognizable subjects in an obvious hierarchy. The Star, Moon, and Sun are striking, they appear in many works of eschatological art, and they are the canonical signa coeli marking Christ's return. Moreover, they admit the possibility of a secondary layer of meaning, a hierarchy of light from the Prince of Darkness (and the Fire from Heaven which triumphs over him) through the Glory of God, resurrection to the New World. This makes a great hierarchy, mnemonic in several ways. As an aside, the female allegory of the Tarot de Marseille World card could easily be interpreted in this context as either Shekinah (sometimes the Presence of God in the form of light) or Lux Mundi (an allegorical figure rather than Christ himself, whom decorum would probably exclude from direct depiction).

Structural patterns, the design of the inventor -- that is the key point here. Everyone sees some of these smaller groupings, like Popess and Pope. It makes sense that the same approach was used throughout, even if they are not all that obvious. Again, the analysis is an iterative process, working from the parts to the whole and working back again from the big picture to the details. Luckily for us, the dozen+ variations in orderings can be analyzed to see which pairings were generally preserved. Just as the Three Worlds structure was preserved in every ordering, the structure of these smaller groupings were preserved in most orderings. Much of the original ordering is preserved in all of the derivative orderings, vestigial remnants of the Ur Tarot. These fossils confirm what should be obvious, and reveal the structure of the work. It should be obvious that Love and Chariot are paired, but the fact that they are usually below Time/Hermit and Fortune confirms it. Likewise, it should be obvious that Time/Hermit and Fortune are paired, but the fact that they are usually between the other two pair in the middle trumps confirms it.

DUMMETT'S RIDDLE OF TAROT

The quest is for the intentio operis, a reflection (perhaps distorted) of the unattainable intentio auctoris, rather than one of the countless unconstrained versions of intentio lectoris. There is no end to the invention of more-or-less plausible audience responses, results of the infamous "what would a 15th-century cardplayer think?" approach. The author's message as he conceived it is not knowable without detailed documentation. However, we have his product, or at least derivative works based on his product. Therefore we can hope to attain some understanding of the underlying design of the work itself, if there is one, and perhaps recreate some of the thinking which went into its creation.

The iconographic puzzle does not have anything to do with how any particular individual might read the series. When it comes to interpreting Tarot cards, as everyone knows, anything goes. Even in the 16th-century commentaries we see incongruities and contradictions, as well as the kind of spit-balling that is typical today. Instead, this analysis is an attempt to explain why specific choices of subject matter and ordering were made, by one person -- the person who selected them and arranged them in that sequence. That is the riddle of Tarot as Dummett framed it and as I have worked on it: "asking why that particular selection was made, and whether there is any symbolic meaning to the order in which they were placed." There may not have been any detailed programme to the composition, but for anyone attempting to find such a program, to go beyond Dummett's vague triumphal sampler of images, that specific, card-by-card outline or schema is a necessary working hypothesis as well as the goal.

It is worth adding a bit to Dummett's statement of the problem, given that you seem to be having trouble making this most basic connection. The iconographic quest asks why that particular selection of subjects was made, and whether there is any symbolic meaning to the order in which they were placed, partly because such a meaningful sequence would be a memory aid for new players as well as a pleasure for everyone. Meaningful content and design are inherently more memorable than, "let's throw in some celestial objects", with no particular reason. Just as groupings into different types of subject matter are too fundamental and obvious to merit much comment from iconographers, I have tended to think that the mnemonic function of a meaningful iconographic programme was too obvious a point to be labored. These are two sides of the same coin, coherent design, and apparently that needs to be spelled out.

A priori, there is no way to know if any surviving deck, or even the unknown Ur deck, actually had a detailed explanation, an iconographic programme with perfect analytical structure. Also, focusing on a derivative deck like those with Justice promoted to serve as Judgment, is by definition addressing Tarot's early reception and revisioning. In terms of methodology, the general order of business might be 1) learn what you can about the generic/synoptic design of the trump cycle, based on all early decks/orderings; 2) learn what you can about the deck which appears display the best, most intelligible programme; 3) explain it as best one can; and 4) explain the other decks as derivatives. At each step, the iterative method of the Hermeneutic Circle applies: parts defining the whole and the whole constraining the parts. When we are debating something as basic as the existence of three sections, or their boundaries, we are at the beginning of step one. Still, most Tarot enthusiasts never get even that far.

THE DEVIL: PLACEMENT AND MEANING

Returning to the Devil, there are several ways in which a devil could be located in the lowest part of a Three Worlds hierarchy. For example, Satan could appear with Adam in the Garden, or as Sin tempting Everyman. Either of these scenes could then be followed by the main allegorical section, then by a transcendent section. As noted, Holbein's Dance of Death is an example. The lowest section is about the Fall. The main allegory is built around individual scenes with an elaborate Ranks of Man, each paired with Death. The final scene shows Christ in the Last Judgment over the World.

A devil could also appear in the middle section, most obviously as an allegory of Sin or Temptation. Satan could also, quite appropriately, appear as the highest card of this section -- as princeps huius mundi. He is the prince of this world, so why not show him triumphing over it? For example, when John is closing his comments (John, 14:30), he says: "I will not now speak many things with you. For the prince of this world cometh, and in me he hath not any thing." The Devil is even the God of this age, deus huius saeculi. "In whom the god of this world hath blinded the minds of them which believe not, lest the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ, who is the image of God." (2 Cor 4:4.)

Paul references the light/darkness trope in his giving thanks: "Giving thanks to God the Father, who hath made us worthy to be partakers of the lot of the saints in light: Who hath delivered us from the power of darkness (de potestate tenebrarum), and hath translated us into the kingdom of the Son of his love, in whom we have redemption through his blood, the remission of sins." (Col-1 12-14.) If we are less concerned with the Three Worlds division, then the Devil can be ambiguous, as can Death, and different arguments can be made using the same quotations.

Of course, he can also appear in the highest realm, as I have argued. Huck stated this clearly: "what about a light state like 'no light'". Darkness is one end of the hierarchy of light. As Lucifer, (shining one, bringer of light), the Morning Star who is also the Prince of Darkness, this subject may be properly grouped with the other light cards. (Wikipedia factoid: Prince of Darkness "is an English translation of the Latin phrase princeps tenebrarum, which occurs in the Acts of Pilate, written in the fourth century, in the 11th-century hymn Rhythmus de die mortis by Pietro Damiani, and in a sermon by Bernard of Clairvaux from the 12th century.") The defining characteristic of the hierarchy of light is that it triumphs over darkness. "Now is the judgment of the world: now shall the prince of this world be cast out." (John 12:31.) That darkness can either be the highest trump of the middle section, or it can be the lowest trump of the highest section.

However, getting back to the idea of explaining rather than merely interpreting, it is difficult to understand any coherent design or systematic programme that does not make the Devil the lowest subject of the highest section. This is where we part ways. You lean more toward Dummett's view, that there is no detailed programme which explains each subject's selection and placement, whereas I believe that there is, and it is not difficult to understand. (I am obviously mistaken in that latter point.) To move beyond the Three Worlds, to "refine" it, is to recognize the smaller units of composition, the nifty nuggets of meaning. We need to make sense of the overall design, the design of each of the three sections, and of the groups within each section. The middle section has a discernible design, a Wheel of Fortune narrative arc which ends with the Traitor and Death. The highest section also has a discernible design, triumphs of the Second Coming, which begins with the triumph over the Devil and ends with the triumph over Death.

You disagree:

"It doesn't matter", although it may "redefine his meaning"? This seems to be a declaration that you no longer consider the meaning to be worth bothering about. That's certainly a legitimate position -- it is closely similar to Dummett's position. But it is abdication of the iconographic project, and that needs to be made clear. Rather than explaining the sequence, it is brushing it aside: this is a sloppy arrangement of subjects, but good enough for a card game.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It doesn't matter whether we place him in the moral section or the third section (however you want to qualify or define it) - he is still in the same place in the sequence in relation to the Thunderbolt in every deck ever made. It may redefine his meaning if he is one or the other section, in the same way that Justice's meaning is changed when she is moved from the moral to the heavenly part (such movements prove that they did indeed read meaning into the sequence, or parts of it).

Dummett's position is that we have to know the original design before we begin. That's just wrong. It would be nice to know in advance, just as it would be nice to know the designer's thoughts on the subject, his name, how he came to create the first deck, etc. However, when it comes to iconography we can work on all the designs we know of and see what each has to tell us. (Dummett, almost inadvertently, advanced this project himself with his 3-segments analysis.) If none of the orderings display a coherent design, a systematic meaning or detailed iconographic program, then iconography brings nothing to the question of which was first. Without such a design, all decks appear to be sloppy derivatives.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:... all the question of the Devil's sectional assignment in A or C really accomplishes is to bring us back to the position Dummett stated - that to know the original meaning, we have to know the original arrangement. It'd be too much to say that we can know what the original arrangement was, but I believe that the strongest argument by far can be made for A, and particularly the Bolognese A.

This leaves only the same old arguments, none of which are very persuasive. Some folks like Bologna, some like Florence, some like Milan, and perhaps some still like Ferrara. Not too long ago, apparently, some of the folks on this List didn't consider Florence to be a contender. At least they acted very surprised when findings began to be published. Now, after those new findings, some of the more simple-minded consider Florence to have been established as the original home of Tarot. Meh. Simpletons will never understand the nature of fragmentary evidence, as demonstrated by those who think every deck with missing trumps is a unique design. Unless some good documentation turns up, such conclusions seem like naive guesswork rather than historical analysis.

Conversely, if there does appear to be some general compositional structures which are more commonly preserved than altered, and if these point to some overall design features of the deck, then we may be able to narrow the field a bit, or even a lot, by taking these into consideration. The fact that the affine pairs and trios are usually grouped together or equally spaced is revealing. They were recognized as meaningful more often than not, and their typical ordering provides context for their proper interpretation. Again, it is an iterative project requiring analysis of individual subjects, 2/3-card groups, the 3 sections, and the overall composition of the hierarchy. And it yields results: Based on this analysis, only two orderings are plausible candidates for the Ur Tarot ordering.

Well, that's... interesting, but not quite clear.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It doesn't matter if you agree with me or like my explanations or the words I use to describe them, or the insights I think they generate. What I mean to say is that it doesn't matter if I convince you with my arguments about the meaning for why this or that "section" or "subsection" exists. What is important, and what I will insist on, is that the following methodological question is sound and crucial - how did the players learn the sequence, which is, by extension, how the designer intended it to be learned? The way the players learned the unnumbered sequence reflects the intent of the designer.

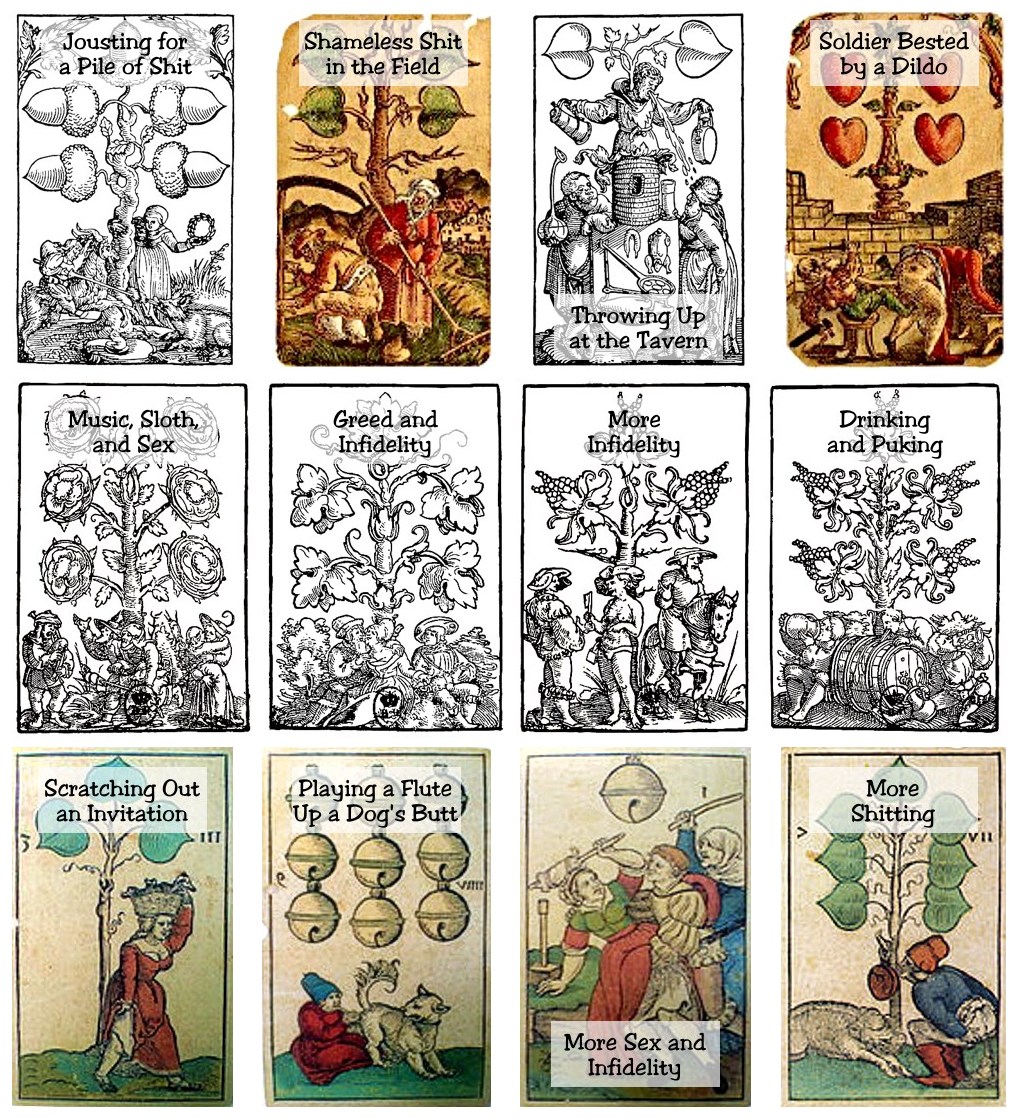

If you mean simply that the design was a mnemonic aid, then yes. That is obviously true, and AFAIK uncontested. An essential point of an allegorical hierarchy as trump cards is that the allegory defines the hierarchy, the ranking of the trumps. Of course, the other essential point of the subject matter is to elevate the game, make it worthy of being played by decent folk, even nobles. It needs to be an inspiring choice, like Marziano's deck, (rather than the tawdry subjects one might find in German card games, as a counter example). Yes, the iconography was an aid to learning as well as a pleasure in playing the game. This is not much of a claim to be presented so melodramatically.

On the other hand, if you mean that the mnemonic requirements tell us something about the iconographic programme, then you are making an amazingly extreme claim. That claim is certainly false. We have some documented examples of what people thought of some of the sequences, and their ideas were quite divergent. Someone-1, attempting to teach the game (including the order of the trumps) to a new player, will do exactly what you claim. He will make the sequence (whichever one they use in his town) as clearly memorable as possible, based on his ideas of the cycle. Someone-2, right down the street from Someone-1, will do the same thing, but their ideas about the trump cycle will be different.

How do I know this? Same way you do -- because everyone's interpretation is different. No one else on earth will teach it quite the same way as Someone-1 does, even if Someone-1 is the designer. Even the designer might not have taught it with the same ideas he used when he designed it. If the design had something complex, subtle, obscure, or otherwise difficult to perceive or explain, then he might offer a simplified or even falsified interpretation to make the order more memorable. He might teach via the visible intention of the work rather than the possibly obscure intention of the author.

Sort of... but each teacher would tell a different tale, and probably none of them would "reflect the intent of the designer" in any detail. And nothing in this process obviates the existence of a coherent design -- just the opposite, it seems to call out for a detailed programme.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:When a new player sat down at the table, never having seen the game before, they learned the trump sequence first by groups, then by habit or memorization.

Just as they were unknowable to cardplayers in 15th-century Italy.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:The groups will reveal the intent of the designer. The specific order of the cards within the groups will be the designer's choice, but may not mean anything beyond his own convenience or whims. These may be unknowable.

You say, "the way the players learned the unnumbered sequence reflects the intent of the designer." But the way players learned the order reflected the intentio lectoris of the teacher, not the intentio auctoris of the inventor. People make up their own connections. This is reflected in pretty much every new topic reflected in posts to the List, as we each see different sub-groups as being more or less meaningful. Each person teaching the game would have their own way of seeing those connections, just as we do today.

One single method used by everyone over the centuries? No. There must have been countless different groupings used by countless players, introducing children and newcomers to the game. Everyone explained it differently back then, as surviving documentation shows and as is the case today.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:In Bologna, the players learned at the table, for the first time, for over 300 years. There must have been a method of groupings to learn the trumps.

There might have been a quasi-standard introduction to the game, but it seems unlikely. When I was a kid, learning both card games and board games, it was never that structured. People (adults) who knew the game would give you some rules. Some would be clear, others would be obscure, and many would be omitted, (some might even be "wrong"), to be picked up in the first few sessions of game play. They would tell you the things that they thought were important, at that moment. Written rules were secondary at best. The order of the trumps would probably be learned in one session/card game, and then fully mastered in the second. It doesn't seem like a difficult problem.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It is the only way to learn it quickly enough to join in common play, when no written rules existed and there were no numbers on the cards.

As illustrated above, it looks like three tweets and a few hands of play is all it would take. The primary argument against a systematic method of teaching is the lack of a consistent ordering from one locale to the next. I have argued that there was intentional alteration of the order, but I don't know of anyone who buys that. The alternative is that each locale learned the order badly from some earlier adopter. In any case, the order of the cards was standardized, but only vaguely, and the explanations would have been even less perfectly standardized.

The best examples of what this might have looked like is the table Marco posted, summarizing the two 16th-century accounts. The categories there, like "Inn of the Fool", are much more in the nature of ad hoc mnemonic aids than they are explanations of the design. This is exactly what we should expect, and what we do in fact find.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:However, since the groupings or mnemonic did not make it into the earliest written or printed accounts of the rules, they must have been easy enough, and banal enough, that they were as quickly learned as forgotten.

Third prediction: When we find such an account, it will look rather like a summary of the two 16th-century commentaries, but somewhat different. It will not reflect the designer's intent in more than a vague sense. Yes, it will have a mnemonic function, and yes, some of the subject matter and themes will be directly related, but how is that random individual who took down some notes going to have figured out what no one else in six centuries could get at?Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:First prediction - somebody of all those players over 300 years must have jotted down an account of their first game of Tarocchi, including an account of the mnemonic. This will reflect the designer's intent. Second prediction - such a jotting will probably survive in a diary, letter, or a single page inserted into a book somewhere. It will probably, but not necessarily, be in Bologna.

This is a fine idea, of course, as would be such a pursuit in any area where the game was played and such private accounts survive.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It is therefore worthwhile to think of ways to search for unpublished diaries and letters that may contain such an account, in Bologna. Of course, it will more probably be an accident that brings it to light, but I believe - predict - that it will be there, somewhere.

It seems unlikely that anyone whose opinion might matter would reject the idea that the trumps were intended to be a memorable hierarchy. Even Dummett, the great iconographic agnostic, would no doubt buy into that. That is one of the primary implications of the whole "Tarot was a game" insight. I've made that argument more than a few times, although I tend to consider it dead obvious. I've even argued that many works of art and literature have compositions which derive from the Scholastic and Encyclopedic traditions, relying on what Ong termed schematic relationships. They were hierarchical outlines, and they were both inherently and sometimes explicitly memory aids.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:I've had time to prepare for utter rejection from everybody, even people whose opinion matters, and it still doesn't matter if my wordy explanations convince or not.

Regarding your placement of the Devil, I think that I offered a good justification, with an assortment of substantiating references, for the Devil's placement at the top of the middle section. That doesn't seem to qualify as utter rejection, at least from me. The argument that Dummett's three segments analysis can be shifted to include higher trumps is also reasonable, because those did not vary in their ordering and Dummett seems to have cared little about the iconographic implications. Death can be moved up or the Devil moved down without violating his concept. Moreover, it seems better to say that you are the one doing the rejecting, as you are the late-comer here. You reject the analysis of Dummett, Shephard, and myself, although I don't quite know why. Yes, there are justifications for putting him where you want him, but I don't see what explanatory value is added by this change.

The difficulty comes when an attempt is made to improve on the Three Worlds analysis, to get into the details. The Three Worlds model is just a starting point, albeit an essential one, and it offers little real understanding of either the iconographic programme or the mnemonic value of the sequence. What is the design within each of these realms? We need to chisel out the details of the middle trumps and the highest trumps from the lumps we call "allegorical" and "eschatological". Again, this is an iterative process of working on one level to understand the others. As we do this, we run into the conceptual nuggets, affine groups, dyads and triads of related subjects and their arrangement. At this point we may either cling to your devilish placement and abandon the quest, or we can accept that the Traitor/Death pair concludes the middle section and the Devil/Fire pair begins the highest. Your placement demands your conclusion: there is no detailed programme. My placement permits a different conclusion: there is a detailed programme.

Yes, the trumps were intended to be noteworthy subjects in a memorable sequence. That's what the iconographic program accomplished. I'm just not getting your point.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:It doesn't even matter if they are fully right or not. My position, my methodology, is inassailable, mainly because it is defending so little. It boils down to the fact that the cards were made to play with, the sequence to be memorized quickly, and the system had to be easy. It had to be fast, and banal enough that it was done so quickly that it was just as quickly forgotten as it was unnecessary, which is why no mention of it has been found yet. It had to be banal. It had to be groups. All we have to do is figure out what the groups were, assign some snappy names to them, and start to play.

Yeah, I guess... I'm not sure what you mean exactly. However, my 22-word summaries would seem to exemplify how this could be done. (It is easy to construct one for the lowest trumps as well, depending on the ordering. See Marco's chart for examples.) You suggest that you've come to some recent realizations, regarding the Three Worlds trope and regarding the mnemonic aspect of the trumps. However, I don't see what is new here except the placement of the Devil within those three groups, and I don't see what that adds.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:The order of the particular cards in them is easy once the groups are down. Why the designer chose those groups is explained by the three classes of subject matter, which I have called for convenience - snappy - earthly, moral, and heavenly. They learned the highest and lowest group first, not an iconographic group, but the only group that mattered in practical terms because it was the only group that counted, literally. The iconography of this ludic group - highest and lowest - then matches where they go in relation to the rest of the cards in their part of the threefold iconographic divisions. This means low people and big ideas.

If the places are arbitrary, in what sense are they explained? Or memorable? The goal should be to find a reading of the trumps and their arrangement which is not arbitrary. Again, this is the great insight of Dummett's riddle -- it's about the sequence.Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote:Why the inventor chose the rest of the particular subjects, or rather why those subjects were obviously groups for the original audience, is the more difficult business, which has to be argued carefully (and usually clumsily by me), from art history and documentary history. I think I've got a good explanation for all the sections, and why each subject would have made clear sense in the group and fallen immediately into its (sometimes arbitrary) place in the group for the original audience, but I know my rhetorical skills are frequently not up to the task of convincing my own audience. Now that I'm standing on firm ground, however, I'm not afraid to keep trying.

Also, rather than arguing from art history and documentary history, which are necessary background but largely uninformative regarding a particular novel work of art, the primary fact is the Tarot trump cards and their known sequences. Tarot enthusiasts are always taking meaning from somewhere else, and giving short shrift to the trumps of an actual deck and how they work together to create meaning.

Finally, regarding the Bolognese deck, I can't really see a pattern in the one or two lights at the top of some cards. Paired cards, like Love and Chariot, might have either one or two lights to indicate the order of the pairs. Temperance, Justice, and Fortitude might have two, one, or no lights, again to indicate their ordering. This could have been used as a mnemonic tool, if it had been done differently. As it actually appears, however, it does not seem to be helpful.

Again, that was fun, and hopefully a productive exercise. Thanks again.

Best regards,

Michael