Ross wrote,

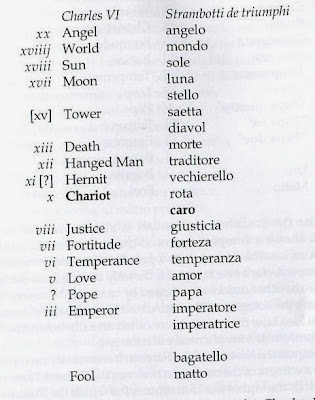

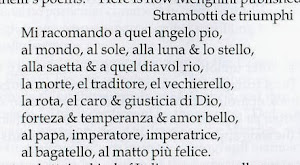

I believe Dummett's assumption was therefore wrong, and that the Charles VI lacked one of the papi by the time it came to be numbered. I also accept the argument that this numbering, like the Strambotto, represents a time of transition in the structure of the trumps in Florence, around 1500. Essentially, they got rid of one of the papi, and moved the Chariot higher. This is what the Minchiate designer inherited.

Thanks for bringing me up to speed on the Charles VI. If it was a transitional deck, my point still stands. Why in Florence would they group the Bagatto, the three papi, and Love together as the low five counting trumps, unless there had first been a previous tradition in which there were four papi and the Bagatto, which naturally look similar?

There is then the question of whether the Fool would have been considered the lowest trump, so that there would have been six "counting cards" at the low end. I don't think so, but I wanted to examine what Dummett says closely. If what he says is in any way out of date, please advise.

Dummett says in his FMR article of 1986,"The Matto is not, strictly speaking, one of the trionfi." Some people on this Forum have taken exception to that statement. In

Game of Tarot, he is more nuanced. Probably it isn't, but it might be, he says. I thought it might be worth looking at his arguments and what they turn on. In Ch. 20, we have, first (p. 419f, and I highlight the most important parts):

Of the Milanese manner of play, we have no direct evidence whatever. Since, however, we have concluded that it was from Milan that the game of Tarot first spread to France and Switzerland, from those countries to reach Germany and other parts of Europe, we have to regard Milan as the ultimate source of all the Tarot games played outside Italy, as well as those played in present-day Piedmont and Lombardy. This means that the original Milanese games were probably very close to what, at the beginning of Chapter 11, were described as being the fundamental three- and four-handed forms of Tarot game, ones in which all the cards are dealt out, save for three or two additional ones taken by the dealer, and in which the counting cards are the court cards and the XXI, Bagatto and Fool, the Fool serving as Excuse.

But then on p. 422f, speaking of Boiardo's poem and Viti's commentary on the game to be played with his cards, he says:

The most frustrating feature is Viti's silence, in the section on how to play with the cards, over the Matto. Possibly he simply assumed that everyone knew how to use the Matto; but the other possibility is that he intended it to be treated as the lowest trump, as in the eighteenth century Piedmontese games of Sedici and Trehtuno. The allusions to it in Boiardo's verses and in the parts of Viti's commentary relating to the cards are maddeningly ambiguous. In the fifth capitolo, which deals with the trionfi, the tercet to be inscribed on the Matto stands first, the subject of the card being given as Mondo; there follow the tercets on the twenty-one trionfi in ascending sequence. From the two lines in the first sonnet relating to the trionfi, it is difficult to tell whether Boiardo is counting the Fool as a trionfo or not: he writes, 'Con vinti et un Trionfo e al piu vil loco/E un Folle, poi che'l folle el mondo adora' ('With twenty-one trionfi, and in the lowest place there is a Fool, because the fool adores the world'). In Viti's commentary the Matto is not spoken of as a trionfo in the paragraph devoted to it, and the next card, Ozio (Idleness) is called the first trionfo, each of them being given a number up to the last one, Fortitude, said to be in the twenty-first place. At the end of the section on the trionfi, Viti speaks of Boiardo's capitolo as divided into twenty-two tercets about 'twenty-two trump cards, with the Matto' (in vintidue carte de Trionfi, con el Matto); the phrase could not have been better designed to leave us in uncertainty whether Viti regards the Matto as a trump or not. Clearly, the Matto is regarded as in some way. different from the twenty-one ordinary trionfi: but whether that is because it plays a quite different role- in the game, as it does when it serves as Excuse, or merely because, like the Miseria of the Sicilian pack, it does not bear a number, it is impossible to tell.

On the one hand, there seems to be a difference between being "the Excuse" and being "the lowest trump". On the other hand, it is a question of terminology: is "trump" being used loosely, to include the "Excuse", or more strictly, to include only cards that trump regular cards.

Dummett then turns to Lollio's account, in verse, of a game in progress among three players. After each round of the deal there is a pause, presumably for betting. At the end of four rounds 20 cards have been passed out. Then it is not clear what happens next, and how many cards each player ends up with. Dummett seems to assume a 78 card deck, but even that is not clear to me! The relevant part comes later (p. 425f; and now I can't pick out any parts more important than others):

And now comes a remark that is really baffling. How many times, Lollio asks, are you unable to cover the Matto? (Quante volte non puoi coprire il Matto?) As a result, you unwillingly find yourself robbed of the good you have gained (Onde mal grado tuo, spogliar ti senti/Del buon c'havevi). What is it to 'cover' the Matto, and why does it have such disastrous consequences? One might conjecture that 'covering' the Matto consisted in giving a card in exchange for it, the player unable to do so having to surrender the Matto. But this can hardly be made to fit the context: a player in such a position is one who has won no tricks, and such a player has no other good to be robbed of. The most natural interpretation of the word 'cover' is 'to play a higher card', i.e. to capture. If this is right, then, in the Ferrarese game, the Matto cannot have served as Excuse, as in the Bolognese and Sicilian games and in Minchiate, but must have been a trump, presumably the lowest one, as in Sedici or Trentuno. Lollio does not mention the Bagatto or Bagatella, save in a general list of trionfi after the description of play; the Matto is here mentioned in just the context where we should expect the Bagatto to be spoken of. The Matto must surely have been a counting card; but that by itself does not explain why a failure to capture it (or, possibly, a failure to bring it home) should have spelled such ruin. Perhaps there was a high premium for bringing it home, or a high penalty for failing to do so; or perhaps, if our earlier supposition that a player scored for particular combinations of cards won in tricks is correct, the Matto could, as in Minchiate, be added to such combinations, or functioned as a wild card, like the two contatori in the Bolognese game, when such combinations were being scored.

In any case, the point seems to be that if a card is a trump, even the lowest one, it can take tricks, and beats any ordinary card, but also be taken by other trumps. If none of these apply, it is the Excuse, and not a trump at all, strictly speaking. He continues (p. 430):

It seems hard to interpret Lollio's question, however, save on the supposition that, for him, the Matto was a low trump which it was of the highest importance to capture; and since, as observed, the poem is the sole direct piece of evidence that we have concerning the way in which Tarot was played in the sixteenth century, we must take it seriously. If, as I have argued, the invention of the Tarot pack represented, if not the first, at any rate an independent invention of the idea of trumps, then it would be a little surprising if, from the first, the Matto had, in play, its special role of Excuse: for that presupposes the simultaneous introduction of two radically new ideas into trick-taking play, whereas, in games, as in other fields, it is rare for anyone to have more than one entirely new idea at a time. The possibility thus arises that originally the Matto was the lowest trump and the Bagatto only the second lowest; if, as seems likely, those two cards were both counting cards from the start, then, at least in the three-handed game, the counting cards in trumps consisted originally of the highest one and the two lowest. We have seen that Lollio's remarks about the consequences of failing to 'cover' the Matto suggest that it was not merely one among several counting cards with a high point-value; and I suggested that perhaps it functioned like a contatore in Tarocchino, that is, as a wild card able to fill gaps in special scoring combinations of cards won in tricks. If so, it would have been seen as a card having a function different from all others, even though it behaved in actual play simply as the lowest trump; and this might serve to explain why it was never numbered or regarded as occupying a numerical position. On this hypothesis, the.invention of its special role in play, as Excuse, must have occurred at some stage after the original invention of the game. If this is correct, this was only the first of two changes of role to which the Fool was subjected in the history of Tarot; as we shall see in Part IV, it later became a trump once more, this time the highest trump, beating even the XXI.

But on the other hand (p. 430):

The only piece of evidence we have for the Matto's having served as the lowest trump are the passage in Lollio's poem and the games of Sedici and Trentuno, which look like a survival from an earlier epoch, but in which the Matto does not have a high point-value; to these we may add, as a very tenuous clue, Pier Antonio Viti's failure to specify the role of the Matto in the game with Boiardo's pack, although he specifies almost all other particulars. Everything else that we know would fit more easily with the supposition that the Matto served as Excuse from the first invention of the game of Tarot. Even Sedici and Trentuno fail to fit perfectly with our hypothesis, because, when it is assumed, it is most natural to think of the type A orders as coming into existence after the introduction of the new way of using the Matto, as Excuse, whereas the fact that in Piedmont the Angelo was treated as higher than the Mondo suggests that it was a type A order that had been familiar there before the game died out.

Exactly why the type A order is hypothesized as coming after the Matto became the Excuse is not clear to me.

If the Matto had been the lowest trump originally, then, Dummett continues, it must have been before the "Steele Sermon". He says:

If the present hypothesis is to be entertained at all, the invention of the new role for the Matto cannot be dated later than the 1470s. The reason for this is that, whereas in Garzoni's book, in Susio's poem and in the Bertoni poem, the trumps are listed in sequence, beginning with the highest, il Mondo (the World), with the Matto coming at the end, the arrangement in the Steele sermon, written at least seventy years before Lollio's poem, is different. In the sermon the trumps are listed in ascending order, beginning with el bagatella, and the Matto, cited as el matto sie nulla (the Fool or zero), still comes at the end, after the 21, which is oddly cited as '21. El mondo doe dio padre' ('21. The World, that is, God the Father'). Moreover, the entry for the Bagatella reads in full 'Primus dicitur el bagatella: et est omnium inferior' ('The first is called the bagatella; and it is the lowest of all'); (9) this explicit statement is immediately preceded by a sentence stating that there are twenty-one trumps (Sunt enim 21 triumphi ...). All this is quite conclusive evidence that the preacher did not regard the Matto as a trump in the proper sense, and did not take it as ranking below the Bagatto.

___________________________

9. The words are here given in full, as in Steele's article, rather than in the severely abbreviated form in which they appear in the manuscript.

If so, what are we to make of Lollio, writing 50 years later? All Dummett can say is that perhaps Lollio in Ferrara had played a "more ancient game" than that described by the Steele's preacher, even though in other areas the Matto was now the Excuse. This is not impossible. So the puzzle remains unsolved.

It seems to me that I have read somewhere that the preacher was himself in the Ferrara area.. If so, it would be preferable to think that Lollio meant something else than how Dummett reads him; or else the change was the opposite of what Dummett is speculating, and that the Matto was first the Excuse, as described by the preacher, but in Lollio's circle and a few other places it became the lowest trump later.

In any case, what is clear that the definition of "trump", for Dummett speaking in his own voice, has solely to do with the role of the card in the game and nothing at all to do with what is depicted on the card, save what is needed for immediate recognition. On the other hand, from Vi is not at all clear that this distinction was always observed in the 15th century. "Trump" for Boiardo and his commentator Viti might have meant something like "special card".

It seems to me that it is of the essence of a trump to trump; but then maybe trumping wasn't so clearly defined in the beginning. It was "triumphing", and perhaps the Matto triumphed if it served its purposes, saving a good card for later in the trick-taking part and racking up points individually and in its role in combinations, whatever it was, during the scoring part of the game.

I realize now I might have misunderstood the thesis expressed by various people that the Matto was the lowest trump. I thought it had to do with the Matto's rank as the lowest order of society. But for Dummett, all that matters is its role in the game, which as the Excuse is the lowest in trick-taking, to be sure, but nonetheless plays a different role than a trump, and unlike a trump can be gotten back at the end of the hand if the player who was dealt it has anything to give in exchange. So when you say the Matto was the lowest trump, did you mean its function in the game, as a trump vs. the Excuse, or something else?