And life goes on till 1545. He must at least have reached an age of more than 60.May 1508:

E’ inviato a Gardenale per impedire il vettovagliamento alle truppe dei Bentivoglio, che vogliono impadronirsi di Bologna ai danni dei pontifici.

May 1509:

Contrasta i veneziani nel Polesine con Bernardino dal Forno, Carlo Strozzi, Rinaldo dal Sacrato e Camillo Costabili al comando di 200 o 225 cavalli leggeri.

1510

....Si trova alla difesa di Zocca sul Po.

August: Viene fatto prigioniero dagli stradiotti di Niccolò Snati nei pressi di Crespino; è condotto a Venezia per essere interrogato dal doge Leonardo Loredan. Rinchiuso in carcere, i pontifici provvedono a confiscare a lui ed al fratello Girolamo i beni da essi posseduti a Modena.

September: Il papa Giulio II richiede ai veneziani la sua consegna per poterlo interrogare su alcune vicende riguardanti il cardinale Ippolito d’Este.

October: Viene consegnato ai pontefici ed è incarcerato in Bologna.

December: Liberato, ritorna a militare per gli estensi. Alla morte di Ludovico della Mirandola è inviato con 100 balestrieri a cavallo a prendere possesso di Mirandola .

For Ippolito Este, cardinal:

Cardinalate. Created cardinal deacon in the consistory of September 20, 1493 [14 years old]; received the deaconry of S. Lucia in Silice, September 23, 1493. On September 28, 1497, he wrote to the pope indicating that he was going to go to Rome, where he had been convoked, after a long delay; arrived in Rome on December 11, 1497; received the red hat on January 8, 1498. Administrator of the see of Milan, November 8, 1497; resigned the post on May 20, 1519 in favor of his nephew Ippolito d'Este. Administrator of the see of Eger, December 20, 1497; occupied the post until his death. Archpriest of the patriarchal Vatican basilica, September 1501. On December 9, 1501, he departed from Ferrara with a cortege of 500 people to accompany Lucrezia Borgia, daugther of Pope Alexander VI, fiancee of his brother Alfonso, on her trip to Rome, where they arrived on December 23rd; the wedding took place at the Vatican on December 30, 1501; he returned to Ferrara after the consistory of February 15, 1503. Administrator of the see of Capua, July 20, 1502; occupied the post until his death. Did not participate in the first conclave of 1503, which elected Pope Pius III; in his haste to go to Rome, he fractured a leg and was unable to attend. Participated in the second conclave of 1503, which elected Pope Julius II. Administrator of the see of Ferrara, October 8, 1503; occupied the post until his death. Administrator of the see of Modena and abbot commendatario of Nonantola, 1507 until his death. Because of the politics of Pope Julius II, he left the Roman Curia in 1507; the pope thanked him however on January 24, 1508 because his part in the repression of the plot of the Bentivogli. During the war of Venice and the pope against the House of Este, he conducted himself with great dexterity at the side of his brother Duke Alfonso I d'Este; he participated in the victorious battle of Policella, December 22, 1509; called to Rome by Pope Julius II on July 27, 1510, he pretended during the trip to have been stricken by a serious illness because he was afraid about the consequences of his conduct against the pontiff; not feeling secure in Italy, he went to his see in Hungary under the pretext that he had been recalled by the king. He was one of the cardinals who, on May 16, 1511, signed a document citing the pope to appear before the schismatic Council of Pisa, to be opened the following September 1st; he detached himself from the other schismatic cardinals in October and the pope allowed him to go to Ferrara; his brother the duke advised him not to participate in the council. Did not participate in the conclave of 1513, which elected Pope Leo X. Enjoying the trust of the new Pope Leo X, he went to Rome; the new pope saw with pleasure the reconciliation between the Bentivogli and the Estensi; on April 22, 1514, the cardinal and all his relatives were pardoned of all the censures they had incurred for having taken part in the wars of Italy. The pope sent him to François I of France and he entered with the monarch in Bologna on December 11, 1515. He went to Poland to attend the marriage of his cousin Bonne Sfroza with King Zygmunt I Stary; he returned through Hungary and France. On January 29, 1518, he received from the pope the faculty of accepting from his brother the duke of Ferrara church properties for him and his heirs and successors. Cardinal protodeacon, June 1519. He was very generous with the poor, friend of writers and artists, and protector of Ludovico Ariosto, "the Italian Homer". His biography was written by Alessandro Sardi.

Julius wanted the control of Ippolito. His interrogation of Masino had this aim.

But anyway, the development in these years is very dynamic:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_the ... of_Cambrai

Simply, Julius II. wanted to proceed with the earlier robbery of Cesare Borgia. He had some success with it, the territory of the Chiesa became larger, Bologna got under control and also Ravenna. He also wanted Ferrara, as earlier his uncle Sixtus IV. This didn't work out, again.

As already said, I could imagine, that the plot of Ferrante and Giulio, brothers of Alfonso, was initiated by Julius. This story happened in late summer 1506.

And this happened very short after:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_II_Bentivoglio"October 7, 1506, Pope Julius II issued a bull deposing and excommunicating Bentivoglio and placing the city under interdict. When the papal troops, along with a contingent sent by Louis XII of France, marched against Bologna, Bentivoglio and his family fled. Julius II entered the city triumphantly on November 10."

In 1504 already Julius desired, that Ferrante should become heir and not Alfonso.

I think, that's the red line through the jungle of information, Julius' II. desire to expand. In his youth Julius as cardinal Giulio Rovere (likely) had plotted against his cousin Girolamo in the Lorenzo Zane scandal. When he had emigrated to France to have some distance between himself and the Borgia, he hesitated not to work for the French invasions in Italy.

***************

I stumbled about this: a description in German language (Gregorovius) from a literary work, that Ercole Strozzi wrote at begin of 1508, before the birth of Ercole II d'Este, the long desired male heir of Alfonso, born in April, about two months before the death of the poet.

He reflects the death of Cesare Borgia, connected to "Olympic scenes", in which it is promised, that the soon born child also would become a hero and would be somehow the rebirth of his uncle Cesare.

Reading this, I remembered, that also the old Roman Julius Caesar died on many knife-stabs. How much?

Wiki says: "According to Eutropius, around 60 or more men participated in the assassination. Caesar was stabbed 23 times." ... and then "A wax statue of Caesar was erected in the Forum displaying the 33 stab wounds."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assassinat ... ius_Caesar

German Wikipedia has also 23, so I think, this is okay, but Italy has: "Dall'esame risultò che una sola delle 18 ferite era da considerarsi mortale, la seconda, per ordine temporale."

Also I note the curious name relationship Cesare - Alexander (VI) - Julius (II). Caesar and Alexander belonged to the Neuf Preux, the 3rd Pagan ruler was Hector (... :-) ... which sound a little bit like Ercole)

In Italian wiki I read about Ercole Strozzi ...

"Lasciò tre figli naturali, Giulia (poi legittimata dopo il suo matrimonio con la poetessa Barbara Torelli), Romano e Cesare."

Again Julius (Giulia) and Caesar.

http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/2413/33

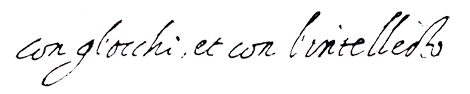

Ercole Strozzi tröstete sie mit pomphaften Versen: er widmete ihr im Jahre 1508 seine Totenklage um Cesar. Dies barocke Gedicht ist durch die Auffassung dieses Menschen merkwürdig, und fast darf man es das poetische Seitenstück des »Fürsten« Machiavellis nennen. Erst zeigt der Dichter den tiefen Jammer der beiden Frauen Lucrezia und Charlotte, die dem Gefallenen heißere Tränen nachweinen, als einst Cassandra und Polyxena um Achill vergossen haben. Er schildert die Heldenlaufbahn Cesars, der dem großen Römer an Taten wie an Namen gleich gewesen sei. Er zählt alle von ihm eroberten Städte der Romagna auf und klagt das neidische Schicksal an, welches ihm nicht erlaubte, deren mehr zu bewältigen; denn sonst würde er Julius II. nicht den Ruhm Bolognas übrig gelassen haben. Der Dichter erzählt, daß zuvor der Genius der Roma vor dem römischen Volk erschienen sei und das Ende Alexanders und Cesars prophezeit habe, klagend, daß mit ihnen die Hoffnung Roms untergehe, es werde aus dem Stamm Calixts einst ein Heiland kommen, wie das die Götter verheißen hatten. Nun belehrt Erato den Dichter über diese Verheißungen im Olymp. Pallas und Venus, jene als Freundin Cesars und der Spanier, diese als italienische Patriotin und unwillig, daß Fremdlinge über die Nachkommen Trojas gebieten sollten, hätten miteinander hadernd vor Jupiter Klage geführt und ihn beschuldigt, seine Verheißung eines Heldenkönigs Italiens nicht erfüllt zu haben. Jupiter habe sie beruhigt: das Fatum sei unwiderruflich. Zwar habe Cesar gleich wie Achill sterben müssen, aber aus den beiden Stämmen Este und Borgia, die von Troja und Hellas hergekommen, werde der verheißene Held hervorgehen. Pallas tritt darauf in Nepi, wo nach Alexanders Tode Cesar an der Pest krank lag, an dessen Lager in Gestalt seines Vaters und verkündet ihm sein Ende, welches er im Bewußtsein seines Ruhmes als Held dahinnehmen solle. Dann verschwindet sie wie ein Vogel und eilt zu Lucrezia nach Ferrara. Nachdem der Dichter den Fall Cesars in Spanien geschildert hat, tröstet er seine Schwester erst mit philosophischen Gemeinplätzen, dann mit der Verkündigung, daß sie die Mutter des prädestinierten Heroenkindes sein werde.