Thanks for the translation, Huck. And yes, I meant Charles of Burgundy, not Charles V.

If cliffs are a Sforza device, then that explains why it's there on the cards. But I'm not sure I know how to tell when something is a heraldic device, as opposed to just a cliff, or that I trust everything I read. For example, everyone says the dove (colomba) is a Visconti heraldic device. But all the evidence I have found (from the songs I quoted earlier) say that it was a turtledove (tortorelle).

I don't think the eductional purpose of cards was simply to educate them in taste. It was mainly to educate them in morality and conduct.

When I say the Fortitude card is idiosyncratic, I mean partly that it is unprecedented; there was never a Fortitude card like it, before or since, that we know of: I mean, the man with the club, Hercules or whoever. Only two out of the many classical accounts of Hercules on http://www.theoi.com/Ther/LeonNemeios.html, even mention the club.Of those, one describes Hercules as swinging it as the lion is charging; the other has him swinging it at the lion as it is running away--not Hercules at his most heroic moment. But everyone mentions his strangling the lion, indeed a moment of great fortitude as well as strength. However it all makes sense if the image (not mentioning Hercules) was one suggested by the Astrolabium.

The Moon card is equally ideosyncratic. You can't just dismiss it by saying it is "uninteresting." It was done that way on purpose, however inept the idea. If it was done as a wedding present, people seeing it would probably take it to be a bad likeness of Ippolita herself (confused with her sister), exchanging Diana's state for marriage. But then why is she so unhappy? Does Lorenzo think this 20 year old was forced into it? It is wholly inappropriate as a wedding gift. As a memorial to a dead sister who married too early, however, it makes total sense.

When I say that 5 of the 6 added cards are not like anything in Ferrara that we have evidence of, I don't mean the style of painting, I mean the content: what is represented in them. I am comparing their content to the d'Este cards, which are our only examples, but not that dissimilar from the Charles VI and Bologna cards.

I am not treating the PMB as a single deck enterprise. Far from it. I have been referring to other decks (page 4 of this thread, Oct. 25). However the evidence I presented earlier suggests that the original PMB was painted earlier than the other decks in that group (except the "Rosenthal," which is hard to say). The Biedak, Guildhall, and Bonomi especially are very similar in style to the 6 new cards, meaning with the rounded, more three dimensional look that those cards have in comparison to the flatter, more Gothic style of the original PMB. Some of them might even have been painted by the same person, or (in the case of, say, the less well executed von Bartsch) a good copyist. And the person on the King of Cups and other court cards in the other decks looks consierably different from the person on the King of Cups in the original deck: older, and more like Ludovico. That is another reason for not supposing that Lorenzo just had them done in a hurry by some random artist. In the other decks, we see the same style in other cards as we do in the 6 cards added to the PMB.

And once again: If Ippolita got them as a wedding present, what did she do with them? Take them to Naples? If she left them in Milan, that's not much of a present. But what was she going to do with 6 cards in Naples?

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

62I was not so interested in doves ... I even had to look at a wiki to see, what a turtle dove is (actually I thught, that all doves could make this "turtle sound"). And what I read, made me think, that it is not easy to see the difference. Maybe it was different in 15. century, when people had naturally more contact to animals.mikeh wrote:Thanks for the translation, Huck. And yes, I meant Charles of Burgundy, not Charles V.

If cliffs are a Sforza device, then that explains why it's there on the cards. But I'm not sure I know how to tell when something is a heraldic device, or that I trust everything I read. For example, everyone says the dove is a Visconti heraldic device. But all the evidence I have found (from the songs I quoted earlier) say that it was a turtledove.

The education of "first sons" differed from the education of others, they also learnt to command and to order and their comrades were trained to obey. I think that the "education in own taste" meets the point better. It's rather clear, that Galeazzo's "morality" education didn't work very well. Dedicated "Rulers" were trained to survive in a nasty world - in vital points "morality" wasn't requested or had a place later in the row.I don't think the eductional purpose of cards was simply to educate them in taste. It was mainly to educate them in morality and conduct.

The man with the club ... that was already antique iconography (for Hercules). Also Samson beat his enemies with the bone of an ass (very near to a club). Both figures were used for Fortitudo, though not in the mainstream. The common "wild man" motif, very often used in Germany, had a club. And ... Morgante had a sort of club, the clapper of a gigantic bell ... just to refer to Lorenzo's background, which also included a relation to Alberti, who filled his Philodoxus with "by Hercules" - exclamations of the actors. And Hercules appeared in the common star pictures, as he was seen as the "astronom", who ordered the stars and another star picture is the zodiac sign Leo ... and it's a good question, if the 12 works of Hercules aren't intended to present the zodiac signs, although a reconstruction, in which way the 12 works nowadays could have been related to the zodiac, seems to be not possible.When I say the Fortitude card is ideosyncratic, I mean that it is unprecedented; there was never a Fortitude card like it, before or since, that we know of: I mean, the man with the club, Hercules or whoever.

You seem to rely on kleio.org's identifications ... which is simply an insecure point. She also identified Mona Lisa ... and a whole complex world is contradicting this hypothesis.Only two out of the many classical accounts of Hercules on http://www.theoi.com/Ther/LeonNemeios.html, even mention the club.Of those, one describes Hercules as swinging it as the lion is charging; the other has him swinging it at the lion as it is running away--not Hercules at his most heroic moment. But everyone mentions his strangling the lion, indeed a moment of great fortitude as well as strength. However it all makes sense if the image (not mentioning Hercules) was one suggested by the Astrolabium. The Moon card is equally ideosyncratic. You can't just dismiss it by saying it is "uninteresting." It was done that way on purpose, however inept the idea.I suppose it could have been done to portray Ippolitta herself, giving up chastity. But it doesn't look like at all like Ippolita; it--along with the other two cards--looks like Elisabetta.

Star - Moon- Sun - Fortitudo - Temperantia - World=Prudentia have a logical equivalent in the 6 palle of the Medici, which by accident or by logical relation appears as a "new heraldic object" in May 1465, just in the same moment - (by accident or by logical relation ?) - of time, when Lorenzo is on his own triumphal journey to the court of Milan and the wedding preparations - and is passing Ferrara (by accident or by logical relation ?). Lorenzo spends too much time in Ferrara, his father is worried (by accident or by logical relation ? did he need time for the production of 6 Trionfi cards ?) and then Lorenzo takes his way to Milan, probably accompanied by Ercole (that means in English "Hercules" - accident or logical relation? ) d'Este.When I say that 5 of the 6 added cards are not like anything in Ferrara that we have evidence of, I don't mean the style of painting, I mean the content: what is represented in them. I am comparing their content to the d'Este cards, which are our only examples, but not that dissimilar from the Charles VI and Bologna cards.

Lorenzo's presence in Milan was a success (what else), as Milan and Florence were already on their way to a great friendship (for a few years), based on the conditions, which the friendship Francesco Sforza - Cosimo de Medici had generated. There were no familiary contacts Medici/Sforza since Cosimo's death (August 1464) and before had been Giovanni's di Medici's death and it was known, that Piero was a sick man and by this it was clear, that this young 15-16-years-old would be the base for the next future.

So .. whatever ideas or presents this young man would have brought to Milan, it would have been welcomed and would have been taken serious ... even if the present would have been nasty and superfluous. And even if it would have been only a simple exchange of politeness for the fact, that young Galeazzo had been welcomed in Florence in a similar grandious way.

The situation is simply so, that the mathematical relations of "too much accident" at a specific moment lead to the "nearly-fact" declaration, that Lorenzo brought this six new elements, so filling the "not documented action" with the detail, that they were based on Medici-ideas ... which would be a logical filling, if we assume some creative movement towards Trionfi cards in Florence before (which was then "specific Florence" - cause we don't see a great Ferrarese movement in this time and neither a great Trionfi card interest in Milan). And we have documents about this movement:

1463 - repeatment of the allowance of 1450; the fact of a repeatment might indicate, that between 1450 and 1463 the allowance was disputed or even redrawn.

1465 - Trionfi festivities in Florence, one focussed on the 3 holy kings

1465 - the appearance of Trionfi cards in Florentine style in Mantova - short after the wedding

1466 - the letter of Pulci in 1466 to Lorenzo de Medici, which gives evidence, that a game called Minchiate existed without security

(For the Florentine Platonic academy we have the founding date 1459, although according a view on the details it might be better to orientate the date towards 1463 - at least it gets a place at Careggi in 1463/64, the villa, in which Cosimo died). So we have two sides of the family ... Cosimo died in his platonic/hermetic dream in a house of death ca. 7 km of Florence, and Piero's wife Lucretzia Tornuaboni kept the boys (often) in a "lucky youth" state in Cafaggioli, the Medici place in about 40 km distance to Florence

Later: Other notes of Minchiate (1471 and 1477), other notes about Trionfi decks exported from Florence (Rome) and the appearance of a deck similar to the Charles VI cards in Pesaro.

And we have the Charles VI deck and some details make it plausible, that it was made in 1463. So the assumption of "unusual Florentine creativity" in matters of Trionfi cards around this time is logical, and an assumed explosion of creative energies in Florence is also logical considering the general potential of this city in the general Italian development of art and art objects. Florence was mostly far ahead - so concludes a man from Florence (Franco Pratesi).

In matters of playing cards Florentine activities were hindered by "more prohibitions in Florence" ... but this condition did change, only to fall back in another form of more dramatic prohibition in the Savonarola-time, which should make it clear, that the conservative forces in Florence were a strong factor.

So "six card ideas from Florence brought to Milan" is from this aspect not surprizing and it's also not surprizing, that it was positively responded in Milan (in the focus on that "golden situation" of Lorenzo in May 1465, as described above).

???? The Lorenzo-hypothesis assumes, that he brought six cards, not a complete deck - so conclusions about the smaller arcana doesn't affect the discussion.I am not treating the PMB as a single deck enterprise. Far from it. I have been referring to other decks (page 4 of this thread, Oct. 25). However the evidence I presented earlier suggests that the original PMB was painted earlier than the other decks in that group (except the "Rosenthal," which is hard to say). The Biedak, Guildhall, and Bonomi especially are very similar in style to the 6 new cards, meaning with the rounded, more three dimensional look that those cards have in comparison to the flatter, more Gothic style of the original PMB. Some of them might even have been painted by the same person, or (in the case of, say, the less well executed von Bartsch) a good copyist. And the person on the King of Cups and other court cards in the other decks looks consierably different from the person on the King of Cups in the original deck: older, and more like Ludovico. That is another reason for not supposing that Lorenzo just had them done in a hurry by some random artist. In the other decks, we see the same style in other cards as we do in the 6 cards added to the PMB.

It seems obvious, that the six cards stayed in Milan. For Ippolita it might be, that she didn't got a wedding deck, as it might be, that playing cards were not accepted in Naples (where she was married to), at least this might have been assumed for Alfonso of Aragon's time (under "normal conditions" she would have got one). It might be, that this prohibitive elements still were ruling in 1465. At least in 1473/74 this negative behaviour was changed (when the Aragon family married some daughters in series), but we have no evidence for an earlier change. Generally it is assumed, that Ippolita influenced the Naples court to more "Renaissance".And once again: If Ippolita got them as a wedding present, what did she do with them? Take them to Naples? If she left them in Milan, that's not much of a present. But what was she going to do with 6 cards in Naples?

Perhaps this prohibitive condition in Naples opened the effectiveness of this present of six cards (... .-) ... about which we discuss till today - and which are really not "great art" - if we abstract from the elegant golden background).

As the present couldn't been given to Ippolita, it was (possibly) redefined to a present of the Medici to the Sforza-family - and as an act of higher pitical politeness it MUST have been taken serious in Milan (it's hardly plausible, that Lorenzo intended this effect; it's not plausible, that the cards were accepted cause their overwhelming great beauty).

At least we have the observable result of a close relationship between Florence-Milan also after Francesco's death, and this was the garant of a more or less stable Italy till 1494, after the first part of the 15th century had seen many wars and especially hostile activities between Milan/Florence.

So Lorenzo's idea got a place in the Milanese deck.

For the meaning of the cards:

The Hercules card idea could have developed from the Sforza heraldic (lion with quitte), from Lorenzo's personal preference for Hercules or from the simple fact, that he was accompanied by Ercole.

The 3 females were probably one woman - probably the bride. It's not sure, that Borso/Lorenzo knew, how Ippolita looked like ... so references to the real outfit probably don't help much.

The sun with (the sun in heraldic presented "first son") wished the birth of a first son.

Two putti on the world card wished more children.

Really not very difficult intentions and ideas.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

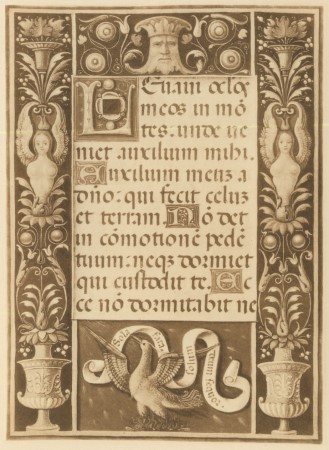

63The difference between the two, doves and turtledoves, is in their respective symbolism, as well as in identifying the different families and individuals who have them as devices. Doves, in Michelino, represented pleasure, as the bird of Venus. In Christianity they represented the Holy Spirit. Turtledoves represent, in Michelino and elsewhere, faithfulness. In relation to families: I have found verification that the phoenix was a device of Bona of Savoy (G. F. Warner, ed., Miniatures and Borders from the Sforza Book of Hours, p. iif). Here is an example of her use of it, from Plate LII of that work, obviously from the time after Galeazzo's death. The motto is the same ""being made lonely, I follow God alone" as quoted by the emblem-writers later, except that instead of "facta" (made) we have "fata," which I assume means "fated."I was not so interested in doves ... I even had to look at a wiki to see, what a turtle dove is (actually I thught, that all doves could make this "turtle sound"). And what I read, made me think, that it is not easy to see the difference. Maybe it was different in 15. century, when people had naturally more contact to animals

Probably it was a device she brought with her from Savoy. If so, every time a Visconti (or a Sforza, after 1450) married a Savoy, it was a Phoenix-Turtledove marriage, as in Shakespeare's poem.

But the correspondence of Francesco to Galeazzo, which I quoted earlier, suggests that morality was high on his list, and in particular that Galeazzo was not to be so arrogant:Dedicated "Rulers" were trained to survive in a nasty world - in vital points "morality" wasn't requested or had a place later in the row.

...he must show politeness to all according to their rank, whether with cap or with hear ow with knee; he must be pleasant of speech with all, not forgetting his own servants;he must keep his hands under control and not lose his temper at every trifle... (Kaplan Vol 2 p. 100)

That is one reason why a man beating a lion would not be particularly welcomed on a triumph card to be used by the children of the Sforza ruling family--it sends the wrong message to the crown prince. Other rulers were not nearly so nasty; or at least they cared about appearances. For example, in either Mantua or Ferrara, I forget which, the ruler walked around town without a bodyguard, according to Lubkin. Galeazzo found that to be astounding and negligent. Of course it was Galeazzo who was assassinated by his friends.

I apologize for my imprecise writing. After writing "there was never a Fortitude card like it, before or since, that we know of: I mean, the man with the club, Hercules or whoever" I should have added, in the same sentence, "...with a lion at his feet just standing there, like on the PMB card." I didn't mean to be talking about men with clubs in general, but the depiction on the PMB card--that depiction is idiosyncratic. There was, to be sure, an iconographic tradition with such imagery, as Ross has pointed out (http://www.trionfi.com/0/i/r/11.html).The man with the club ... that was already antique iconography (for Hercules).

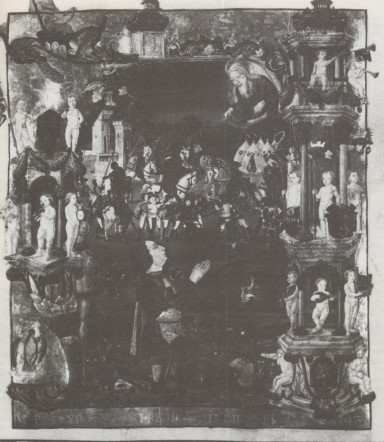

I have found additional evidence for my hypothesis that the card was commissioned by Galeazzo as a talisman for obtaining victory in his new goals of 1474-1475, getting recognition from the emperor as not only a duke but a king, and benefiting from his alliance with Charles of Burgundy. Kaplan has a full-page reproduction of what must have been a large, expensive painting of Galeazzo "praying for victory" (Kaplan's words) to an attentive God {Vol. 2, p. 103). Galeazzo looks about 30.

Yes, forget about the dubiousness of kleio.org. Here is what I should have said:You seem to rely on kleio.org's identifications ... which is simply an insecure point.

The Moon card is equally idiosyncratic. You can't just dismiss it by saying it is "uninteresting." It was done that way on purpose, however inept the idea. I suppose it could have been done to portray Ippolitta herself, giving up chastity for marriage. But then why does the lady on the card look so unhappy? Is her marriage a sad occasion? The expression on the lady's face seems inappropriate to the occasion. In contrast, the sad expression would fit Elisabetta, marrying at 13, probably against her will. Ippolita was 19.

The only thing the 6 palle (balls) on the Medici shield have in common, that I can see, with the 6 added cads is the number 6. That's not much on which to base 6 cards, 4 of them fairly novel, unlike any other corresponding cards of that time. And actually, at that time, the shield apparently had 7 balls. Here is a quote from an article about them (http://italian.about.com/library/weekly/aa091599a.htm):Star - Moon- Sun - Fortitudo - Temperantia - World=Prudentia have a logical equivalent in the 6 palle of the Medi

Originally there were 12; in Cosimo dé Medici's time it was seven; the ceiling of San Lorenzo's Sagrestia Vecchi has eight; Cosimo I's tomb in the Cappelle Medicee has five; and Ferdinando I's coat of arms in the Forte di Belvedere, six.

Now I want to get back to the cliffs, which you say was a Sforza device. Perhaps what you read was that the cliffs was associated to the monastery of Certosa of Pavia, founded by Caterina Visconti. Kaplan (Vol 2 p. 47) shows a picture of an altar cloth depicting it perching on a cliff. Giangaleazzo, Caterina's husband, began work on the monastery, and Francesco Sforza began construction on the main part of the church there. Kaplan concludes,"'For some one hundred years, the Visconti and Sforza families were closely associated with the Certosa and it would not be unreasonable to expect some indication of this important association to appear in the tarocchi cards" (p. 48).

A device is usually the same image repeated in different contexts. But the cliff on the cards is done in different ways. Here is the Fool.

And here is Death:

The Temperance card repeats the indentations of the Death card quite precisely:

So did Borso convey exactly this image to Lorenzo, from somewhere? And then also convey to Lorenzo that he could take liberties with this image, varying the indentations in the cliff from card to card? For example, the Star card is different:

It seems to me that rather than saying the cliff was a device, it would make more sense to say that Borso had copies of the original PMB cards, which he lent to Lorenzo. I don't know if that would be a realistic assumption or not.

Personally I prefer to think that either the new cards were made in the same shop as the old ones, which had sketches or copies to work from, or the owner of the old cards lent them to the painter of the new cards, so as to promote consistency of design. In connection with the first of these alternatives, let me cite an observation by Dummett (from Artebis Historiae 56, p. 22):

"Sandrina Bandera, in the catalogue to the Brera exhibition of the three packs by Bonifacio Bembo, emphasises the production by the Bembo workshop of paintings and of decorated objects of all kinds; she also stresses the use by such workshops of "sketch-books" containing standarised motifs which could be used in different works. "

So the second artist, whom Dummett thinks was Benedetto Bembo, could simply look at the sketch-books, or even the first artist's cards themselves, which he thinks were produced at the same time as the second artist's, by his brother Bonifacio. I have thoughts about Dummet's thesis, a thesis that needs to be assessed in comparison to both your and my hypotheses; but these thoughts can wait until a later post.

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

64I think, that the last part of Dummett's article (inclusive the Benedetto Bembo suggestion) is not very interesting ... I've only seen fotos, but it seems, that the differences, according which the work of the first painter was parted from the work of the second, included differences in the (resulting) color of the golden background. Perhaps he used another sort of gold ... which should be then not a sign of the same workshop. The used gold is possible more thin (and for this the gold has less relief and has more light) for the second artist and you more often have red spots, possibly going back to damage by use. The relief effect is far more impressive for the cards of the 1st artist (a great variation and exception is at the lover cards, which has a "red gold" or whatever as background).mikeh wrote: The difference between the two, doves and turtledoves, is in their respective symbolism, as well as in identifying the different families and individuals who have them as devices. Doves, in Michelino, represented pleasure, as the bird of Venus. In Christianity they represented the Holy Spirit. Turtledoves represent, in Michelino and elsewhere, faithfulness. In relation to families: I have found verification that the phoenix was a device of Bona of Savoy (G. F. Warner, ed., Miniatures and Borders from the Sforza Book of Hours, p. iif). Here is an example of her use of it, from Plate LII of that work, obviously from the time after Galeazzo's death. The motto is the same ""being made lonely, I follow God alone" as quoted by the emblem-writers later, except that instead of "facta" (made) we have "fata," which I assume means "fated."

Probably it was a device she brought with her from Savoy. If so, every time a Visconti (or a Sforza, after 1450) married a Savoy, it was a Phoenix-Turtledove marriage, as in Shakespeare's poem.

In the case, that it was from Savoy, we've the problem, that the Michelino deck was probably made ca. 1425 (and that seems to be the latest date, we could reasonable give) and the marriage of Filippo Maria to a Savoy princess happened in 1427 (and, as far we know, was not thought of before, but arrived as an alternative cause of the run of the current war).

Well, that was from a letter from Francesco Sforza to Galeazzo, not Galeazzo's real behaviourBut the correspondence of Francesco to Galeazzo, which I quoted earlier, suggests that morality was high on his list, and in particular that Galeazzo was not to be so arrogant:

...he must show politeness to all according to their rank, whether with cap or with hear ow with knee; he must be pleasant of speech with all, not forgetting his own servants;he must keep his hands under control and not lose his temper at every trifle... (Kaplan Vol 2 p. 100)

Galeazzo aimed at this goal, but it is not confirmed, that he got "recognition". ...I apologize for my imprecise writing. After writing "there was never a Fortitude card like it, before or since, that we know of: I mean, the man with the club, Hercules or whoever" I should have added, in the same sentence, "...with a lion at his feet just standing there, like on the PMB card." I didn't mean to be talking about men with clubs in general, but the depiction on the PMB card--that depiction is idiosyncratic. There was, to be sure, an iconographic tradition with such imagery, as Ross has pointed out (http://www.trionfi.com/0/i/r/11.html).

I have found additional evidence for my hypothesis that the card was commissioned by Galeazzo as a talisman for obtaining victory in his new goals of 1474-1475, getting recognition from the emperor as not only a duke but a king, and benefiting from his alliance with Charles of Burgundy. Kaplan has a full-page reproduction of what must have been a large, expensive painting of Galeazzo "praying for victory" (Kaplan's words) to an attentive God {Vol. 2, p. 103). Galeazzo looks about 30.... you've to prove this "recognition".

Actually the duke of Burgund and the emperor met in war (at Neuss, Novesia) ...

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belagerung_von_Neuss

Burgund and his alliance had 10.000 dead men, the defenders had between 700 and 3000 victims. The battle between Emperor and Burgund didn't really take place, as Burgund retired, when the army of the emperor arrived.

Then there were negotiations. Then there were new wars with Burgund testing his army in Switzerland. The test didn't work, istead there were great losses Then suddenly Galeazzo was dead and two weeks later Charles the bold. Maximilian as emperor's son married the heiress of Burgund ... after her father had died.

Generally it's difficult (and a little absurd) to speak of the"ideosyncrasy of early tarot cards", as we have from each Tarot motif only a few examples. How should we know, what is ideosyncrasy in such a context?

She looks so sad, cause the painter is so bad and not capable to do it better.The Moon card is equally idiosyncratic. You can't just dismiss it by saying it is "uninteresting." It was done that way on purpose, however inept the idea. I suppose it could have been done to portray Ippolitta herself, giving up chastity for marriage. But then why does the lady on the card look so unhappy? Is her marriage a sad occasion? The expression on the lady's face seems inappropriate to the occasion. In contrast, the sad expression would fit Elisabetta, marrying at 13, probably against her will. Ippolita was 19.

... .-) ... I get reason to become angry. The six-palle-model was chosen in May 1465, and that was mentioned at the start, when I talked about it .... It's true, that before other numbers of palle's was used.The only thing the 6 palle (balls) on the Medici shield have in common, that I can see, with the 6 added cads is the number 6. That's not much on which to base 6 cards, 4 of them fairly novel, unlike any other corresponding cards of that time. And actually, at that time, the shield apparently had 7 balls. Here is a quote from an article about them (http://italian.about.com/library/weekly/aa091599a.htm):Star - Moon- Sun - Fortitudo - Temperantia - World=Prudentia have a logical equivalent in the 6 palle of the Medi

Originally there were 12; in Cosimo dé Medici's time it was seven; the ceiling of San Lorenzo's Sagrestia Vecchi has eight; Cosimo I's tomb in the Cappelle Medicee has five; and Ferdinando I's coat of arms in the Forte di Belvedere, six.

The choice of the motifs: 3 cardinal virtues were connected (not Iustitia) at least by feathers to the heraldic device. The sun-moon-star-trio is probably given by the Medici-Chapel and the 3 holy kings ... both was argumented before.

In practice many devices are variated.Now I want to get back to the cliffs, which you say was a Sforza device. Perhaps what you read was that the cliffs was associated to the monastery of Certosa of Pavia, founded by Caterina Visconti. Kaplan (Vol 2 p. 47) shows a picture of an altar cloth depicting it perching on a cliff. Giangaleazzo, Caterina's husband, began work on the monastery, and Francesco Sforza began construction on the main part of the church there. Kaplan concludes,"'For some one hundred years, the Visconti and Sforza families were closely associated with the Certosa and it would not be unreasonable to expect some indication of this important association to appear in the tarocchi cards" (p. 48).

A device is usually the same image repeated in different contexts. But the cliff on the cards is done in different ways.It's likely, that Borso knew or had Sforza cards. Borso produced Trionfi cards himself and showed a general interest in the cards. The relations between Ferrara and Milan were good (and important) in Francesco's time, in Galeazzo's time they became bad soon. So Borso knew the Sforza's cards. If he didn't know them, who then? Or do you insist in this case on a single-deck-version? We know by evidence, that various decks existed. We know, that the Sforzas were not very creative, but repeated the motifs.It seems to me that rather than saying the cliff was a device, it would make more sense to say that Borso had copies of the original PMB cards, which he lent to Lorenzo. I don't know if that would be a realistic assumption or not.

Personally I prefer to think that either the new cards were made in the same shop as the old ones, which had sketches or copies to work from, or the owner of the old cards lent them to the painter of the new cards, so as to promote consistency of design. In connection with the first of these alternatives, let me cite an observation by Dummett (from Artebis Historiae 56, p. 22):

"Sandrina Bandera, in the catalogue to the Brera exhibition of the three packs by Bonifacio Bembo, emphasises the production by the Bembo workshop of paintings and of decorated objects of all kinds; she also stresses the use by such workshops of "sketch-books" containing standarised motifs which could be used in different works. "

So the second artist, whom Dummett thinks was Benedetto Bembo, could simply look at the sketch-books, or even the first artist's cards themselves, which he thinks were produced at the same time as the second artist's, by his brother Bonifacio. I have thoughts about Dummet's thesis, a thesis that needs to be assessed in comparison to both your and my hypotheses; but these thoughts can wait until a later post.

As this is not really attested at the real cards, but only at the fotos, this observation is not reliable.

Anyway, it doesn't look like the "same workshop".

Dummett's suggestion, with which he kicked the temple "standard Tarot existed ca. 1450" (well, not our temple) quickly in the corner for overcome assumptions, is not very sensible with the general Milanese background and also not to our general assumption, that early Trionfi cards were objects for "triumphal moments". The article was written in the time, when Trionfi.com already existed - Dummett overlooked its existence or wanted to overlook it (although his partner John McLeod had a detailed knowledge to some Trionfi.com hypotheses, not probable, that he could overlook it).

So the last part is a poor, not very detailed, contribution, which takes a rather quick end, so as if he fears Pandora's box, which would urge, that he has to make much more words ... the first part is excellent.

But let's forget about it ... trionfi.com has developed a lot of complex topics and it's understandable, that specific persons don't wish to be involved, we just too often talk about matters, about which they never heard of.

... .-) ... a certain problem for an expanding theory, which contradicts many other hypotheses.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

65

... this is a late interpretatation about a coin, which was assumed nearly 100 years ago ... it easily might be, that the author actually saw the common Visconti dove.

But perhaps she really took the phoenix as the symbol ... then we have this picture:

.. from which Kleio.org said, that it presents Galeazzo and Bona of Savoy (in this case we coincide; Pollaiuolo had opportunity to paint the both during the Galeazzo visit in Florence ; the (early) interest on Daphne by the Sforza is testified by other manuscripts and other paintings)

Generally Galeazzo is said to have been interested in the art of his ancestors, also that of Filippo Maria Visconti. So he might taken the preference for the Daphne motif from the Michelino deck ... as he (possibly) identified Bona in some aspects as "Daphne" (one might imagine, in which), Bona might have taken the phoenix from this context. So no need to exspect a Savoyan phoenix.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

66I apologize for my tone in discussing the balls. I will try to be less assertive on things I know about only from the Internet.

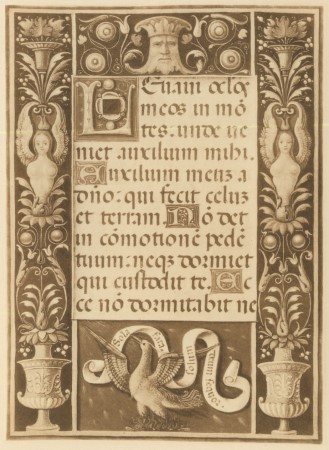

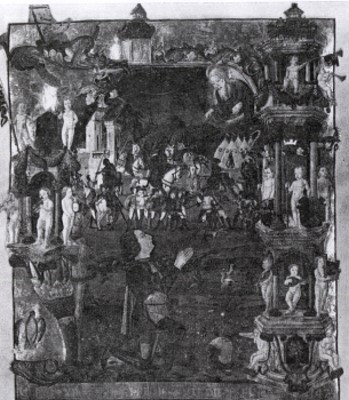

On the Phoenix. Yes, I saw that picture of the phoenix you posted, with the accompanying anecdote, in the book on Google, Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers.. And I, too, wondered whether the emblem writer had gotten the bird right. The image I posted in my last post was from the Sforza Book of Hours, done for Bona Sforza sometime after Galeazzo’s death in 1476 but before she moved to France in 1495. The image confirms that the bird was indeed the phoenix. I got it from a book published in 1894 by the British Museum, with black and white photos of most of the miniatures and borders. The phoenix is in Plate XLII. Here is the whole page:

The editor, George F. Warner, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts at the Museum, explains that the book identifies Bona in various places: the words “Diva Bona,” “Bona Duc,” and the initials “B.M.,” standing for “Bona Maria.” Warner also cites apparently reputable sources to verify the story about the coins: Gnocchi, Il Monete di Milano 1884, p. 83, pl. XV. 2 and Litta, Famiglia Celebri Italiano, Sforza pedigree, tab. v no. 9. However in rereading him I see that he doesn't say it was a Savoy device, just that it was Bona's device (p. ii and xxv). I have read somewhere that it was a Savoy device. I will keep looking.

Warner has an interesting story about the history of the book. It ended up in the collection of Emperor Charles V. Hence Bona must have given it to her daughter Bianca when she married Emperor Maximilian in 1493. And when she died it would have remained with the Emperor, until he died, when it went to the next emperor. The interesting part is that sometime before it got to Charles, somebody removed 16 of the 64 pages, leaving only 48. So what Charles did was to insert 16 new ones, including one with a portrait of himself and the date 1520. The 48 old ones are in the Italian style, by one artist; the new ones are in the Flemish style, but probably done in Spain, by two or more artists, with an effort to imitate the Italian calligraphy.

Warner has a theory for why the pages were removed. He speculates that the book was originally prepared as a gift to Bianca to bring to her earlier prospective husband, Matthias, King of Hungary. Then when she married Maximilian instead, all images which might be taken to refer to Matthias were removed, as there was a bitter rivalry between Matthias and the House of Hapsburg (Warner p. viii). But the censors missed one, Warner points out, a small picture of St. Elizabeth of Hungary. The censors apparently hoped that Maximilian would not notice the doctoring job. Warner admits the weakness of his theory. Another possibility, it seems to me, is that someone (such as Bianca, who often told Maximilian her allowance was too small) might have sold these pages for money.

The point is that people in those days did not necessarily have any more respect for the integrity of a collection of miniatures (such as cards) than they have had more recently. If the price is right, or if some are offensive, then some of them go away, perhaps never to be recovered. And then someone else can add new ones if they want!

The book also has a few interesting portraits, unidentified but probably of Bianca Maria (the mother-in-law), Bona, and Gian Galeazzo, according to Warner. The miniatures before and after the one with the phoenix are also interesting. The one before it shows a putto playing with a baby lion (Gian Galeazzo with the lion that Galeazzo bought him?). Next come three persons at a tomb, with someone’s bare feet sticking out (Galeazzo?). Then comes one of the putto playing with some ermine (faithfulness?). Next is the putto playing with a dragon, then him playing with a snake. Then comes just a sleeping lion, then one of the putto playing with two snakes, then a lady giving alms to a beggar (charity?), and then one of a lady pointing up to heaven with stars in the background (hope?). After that, at the end, are the portrait of Charles V and some other Flemish miniatures. I am thinking that the putto is Gian Galeazzo as the infant Hercules. The borders remind me of the pseudo-Egyptian frescoes in the Borgia Apartments.

On the Phoenix. Yes, I saw that picture of the phoenix you posted, with the accompanying anecdote, in the book on Google, Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers.. And I, too, wondered whether the emblem writer had gotten the bird right. The image I posted in my last post was from the Sforza Book of Hours, done for Bona Sforza sometime after Galeazzo’s death in 1476 but before she moved to France in 1495. The image confirms that the bird was indeed the phoenix. I got it from a book published in 1894 by the British Museum, with black and white photos of most of the miniatures and borders. The phoenix is in Plate XLII. Here is the whole page:

The editor, George F. Warner, Assistant Keeper of Manuscripts at the Museum, explains that the book identifies Bona in various places: the words “Diva Bona,” “Bona Duc,” and the initials “B.M.,” standing for “Bona Maria.” Warner also cites apparently reputable sources to verify the story about the coins: Gnocchi, Il Monete di Milano 1884, p. 83, pl. XV. 2 and Litta, Famiglia Celebri Italiano, Sforza pedigree, tab. v no. 9. However in rereading him I see that he doesn't say it was a Savoy device, just that it was Bona's device (p. ii and xxv). I have read somewhere that it was a Savoy device. I will keep looking.

Warner has an interesting story about the history of the book. It ended up in the collection of Emperor Charles V. Hence Bona must have given it to her daughter Bianca when she married Emperor Maximilian in 1493. And when she died it would have remained with the Emperor, until he died, when it went to the next emperor. The interesting part is that sometime before it got to Charles, somebody removed 16 of the 64 pages, leaving only 48. So what Charles did was to insert 16 new ones, including one with a portrait of himself and the date 1520. The 48 old ones are in the Italian style, by one artist; the new ones are in the Flemish style, but probably done in Spain, by two or more artists, with an effort to imitate the Italian calligraphy.

Warner has a theory for why the pages were removed. He speculates that the book was originally prepared as a gift to Bianca to bring to her earlier prospective husband, Matthias, King of Hungary. Then when she married Maximilian instead, all images which might be taken to refer to Matthias were removed, as there was a bitter rivalry between Matthias and the House of Hapsburg (Warner p. viii). But the censors missed one, Warner points out, a small picture of St. Elizabeth of Hungary. The censors apparently hoped that Maximilian would not notice the doctoring job. Warner admits the weakness of his theory. Another possibility, it seems to me, is that someone (such as Bianca, who often told Maximilian her allowance was too small) might have sold these pages for money.

The point is that people in those days did not necessarily have any more respect for the integrity of a collection of miniatures (such as cards) than they have had more recently. If the price is right, or if some are offensive, then some of them go away, perhaps never to be recovered. And then someone else can add new ones if they want!

The book also has a few interesting portraits, unidentified but probably of Bianca Maria (the mother-in-law), Bona, and Gian Galeazzo, according to Warner. The miniatures before and after the one with the phoenix are also interesting. The one before it shows a putto playing with a baby lion (Gian Galeazzo with the lion that Galeazzo bought him?). Next come three persons at a tomb, with someone’s bare feet sticking out (Galeazzo?). Then comes one of the putto playing with some ermine (faithfulness?). Next is the putto playing with a dragon, then him playing with a snake. Then comes just a sleeping lion, then one of the putto playing with two snakes, then a lady giving alms to a beggar (charity?), and then one of a lady pointing up to heaven with stars in the background (hope?). After that, at the end, are the portrait of Charles V and some other Flemish miniatures. I am thinking that the putto is Gian Galeazzo as the infant Hercules. The borders remind me of the pseudo-Egyptian frescoes in the Borgia Apartments.

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

67... I don't mind your assertions, but the fact, that I've to repeat myself in a stuff, that I've written often enough ...mikeh wrote:I apologize for my tone in discussing the balls. I will try to be less assertive on things I know about only from the Internet.

It's nice, that you found the phoenix. I think, I knew the picture, but I didn't note the phoenix, well, it didn't interest me then. I assume, that you got your informations from the text of 1895.

Around the object now exist rather different theories ... according to new findings. So you can forget about your dates, at least partly. Recently (3 years ago) a picture with Bona on hawk hunting tour was detected, which belonged to the incomplete manuscript ... for rather much money it was bought and it was a big show for a British Museum, as far I remember. And the manuscript was involved in a sort of criminal case ... made ca. 1490, as far I remember.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

68Well, I miss things the first time around sometimes. Like for example, this time I missed the part about the feathers.... I don't mind your assertions, but the fact, that I've to repeat myself in a stuff, that I've written often enough...

I don't understand what you mean. What feathers, and connecting the virtues to what in the heraldic device? I realize I need to understand more about the di Medici and their symbolism at that time, 1465. Can you give me a good reference, preferably in English, that talks about the balls and the feathers, why it was six balls and not five or seven, Lorenzo's interests and personality at that time, etc?The six-palle-model was chosen in May 1465, and that was mentioned at the start, when I talked about it .... It's true, that before other numbers of palle's was used.

The choice of the motifs: 3 cardinal virtues were connected (not Iustitia) at least by feathers to the heraldic device.

Yes.I assume, that you got your informations from the text of 1895.

You lost me. What object? The book, the phoenix? And what dates? That sounds interesting.Around the object now exist rather different theories ... according to new findings. So you can forget about your dates, at least partly.

And now I need to respond to a few things in your earlier post.

In 1465 and earlier it is not Galeazzo's real behavior that matters, as far as what is appropriate to put in an educational game, it is his conduct as perceived by his parents; they are the ones being given some of the presents at Ippolita's wedding (you say) and are the ones still trying to educate him. And we know that Bianca Maria continued be at odds with Galeazzo, still trying to educate him, until her death (whatever the facts about his alleged poisoning of her and her alleged threat to give Cremona over to Venice).Well, that was from a letter from Francesco Sforza to Galeazzo, not Galeazzo's real behaviour.

Likewise in 1474-75, the issue is not whether Galeazzo actually obtained any victories or recognition; pretty clearly he didn't. It is his hope of victories, his attempt to obtain victories of the sort I indicated, that matters.Galeazzo aimed at this goal, but it is not confirmed, that he got "recognition". ...... you've to prove this "recognition".

I don't hold to a single-deck theory. I just didn't see why Borso would have had a copy of the PMB deck lying around in 1465. In Ferrara they had their own decks. But if he was an aficionado, he might have had one. It is unforunate that all these many decks in Ferrara got lost, until the d'Este in the 1470's. They weren't as meticulous about keeping cards as they were manuscripts and art objects....Or do you insist in this case on a single-deck-version?...

The coloration of the 2nd artist’s cards certainly looks different from those of the 1st artist’s, as well as their state of preservation. But I do not see how from that we can conclude that the cards were from different workshops. They might be from the same workshop at different times. Artists had much more freedom to change their paints than they did their subject matter and style, especially if the results held up better. It is possible, although not likely, that different artists in the same workshop at the same time even preferred different mixes.I think, that the last part of Dummett's article (inclusive the Benedetto Bembo suggestion) is not very interesting ... I've only seen fotos, but it seems, that the differences, according which the work of the first painter was parted from the work of the second, included differences in the (resulting) color of the golden background.Perhaps he used another sort of gold ... which should be then not a sign of the same workshop. The used gold is possible more thin (and for this the gold has less relief and has more light) for the second artist and you more often have red spots, possibly going back to damage by use. The relief effect is far more impressive for the cards of the 1st artist (a great variation and exception is at the lover cards, which has a "red gold" or whatever as background).

As this is not really attested at the real cards, but only at the fotos, this observation is not reliable.

Anyway, it doesn't look like the "same workshop".

Now I want to get to the main subject of this post: Dummett. The end of his article has some interesting ideas, even though not pursued adequately. Here is the last paragraph of the essay (Artibus Historia 56 (2007), pp. 15-26), where he finally says something positive on the question "Who really painted the six cards?"

There are several theses here. One is in the statement near the end that "she probably gave it to Cremona during the two years between his death and hers." That refers to an earlier argument that since all the other PMB-style decks are copies of the PMB, as opposed to the Brambilla or Visconti di Madrone (Cary-Yale), the Bembo workshop must have had the PMB available to them to make the copies. I quoted from the earlier paragraph in an a previous post, but here is the whole thing:The most probable attribution seems to me to be to Benedetto Bembo, an artist agreed to have been influenced by Ferrarese art, as shown by the female figures on the Temperance, Star and Moon cards. These figures, with their high foreheads and pursed lips, have affinities with the Madonna and female saints in Benedetto's Torrechiara polyptych, now in the Castello Forzescho in Milan, and his Madonna of Humility, now in the Museo Civico, La Specia, and probably painted in Ferrara. The very expressive male heads in the polyptych are close to the male figure on the Fortitude card, and the particularly curly russet hair of the boy on the Sun card and of the putti is characteristic of Benedetto. The pack was the product of the Bembo workhop: of the surviving 35 picture cards, Benedetto executed six and Bonifacio the remainder (missing are the Devil, the Tower or Lightning and the Cavallo di Denari). Benedetto's earliest datable work is the Torchiara polyptych, signed and dated by him to 1462. The pack must therefore have been painted in the early 1460's. It may have been made for Bianca Maria, or she may have inherited it from her husband; in either case she probably gave it to Cremona during the two years between his death and hers. On the hypothesis that Benedetto painted the six cards, there is no need to suppose the original versions of them to have been lost or damaged: we have the original versions.

That person, of course, is Bianca Maria. (In a footnote, Dummett explains that what Bianca asked for was "carte de trionfi," of course, not "tarot cards.") But if the Bembo workshop indeed made the PMB in the first place, they might at that time have kept on hand the "sketchbooks,” with which to fill future orders from the same customer. Then they would have no need to borrow the original back again. However 1466-1468 would have also been convenient.From a letter of 1451 from Bianca Maria Visconti to her husband Francesco Sforza, asking him to send to Sigismondo Malatesta, lord of Rimini, a pack of tarot cards of the kind made in Cremona, which he had asked for the previous autumn, we may infer that Cremona was especially renowned for hand-painted playing cards of this kind. Sandrina Bandera, in the catalogue to the Brera exhibition of the three packs by Bonifacio Bembo, emphasises the production by the Bembo worhop of paintings and of decorated objects of all kinds; she also stresses the use by such workshops of “sketchbooks" containing standardized motifs which could be used in different works. Almost all of the fragmentary sets are probably authentic, and if the packs from which thye derive were painted in Cremona, it thus seems likely that in the later XV or early XVI century the Colleoni pack was held in Cremona, and was available to artists to copy from. It must have been given to the city by some member of the ducal family who had a particular connection with Cremona.

Dummett's other theses have to do with Benedetto Bembo, first, that he is the second artist; second, that he painted the six cards in "the early 1460's," and third, that Bonifacio painted the others at that time, too. I do not want to discuss when the original cards were done, as we have already gone over that, and it doesn't look like the early 1460's. Instead, I will focus on what Dummett says about the second artist.

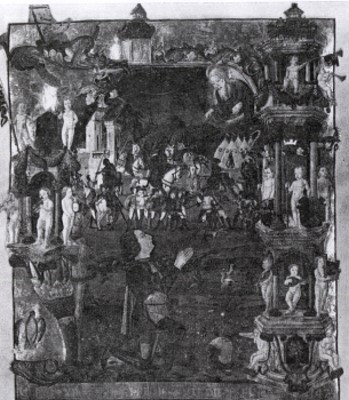

To show that Benedetto painted the six cards, he compares different cards to different aspects of the Torrechiara polyptych and perhaps also the Madonna of Humility. It took me a while to find the Torrechiara, but here it is, from Steffi Roettgen's Italian Frescoes: The Early Renaissance, p. 358:

To me this looks very International Gothic, and not very "Ferrarese," if I understand the term. Adolfo Venturi, writing in 1931, called this work "one of the most notable examples of the relationship existing betwen the art of Lombardy and the great school of Padua" (/i]North Italian Painting of the Quattrocento: Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria[/i], p 12f). Roettgen calls it "of the Venetian type" (p. 359). Dummett calls our attention to the "expressive faces" of the males. I don't see much expression, except for Gothic devoutness. There is nothing of the secular emotionality of the Ferrara painters (as exhibited e.g. in the Schifanoia frescoes). One of the faces is mostly obliterated, but here is a closer view of the other four:

Then Dummett talks about the "high foreheads and pursed lips" of the Madonna and female saints, similar to the Temperance, Star, and Moon cards. Well, I looked at a bunch of Lombardy Madonnas and other women from that period and before. Quite a few have high foreheads and pursed lips. That seemed to have been the fashionable way to portray high-born women, at least in Lombardy. Look, for example, at this scene from Monza Cathedral (Roettgen, Italian Frescoes: The Early Renaissance, plate 96:

Another example is this Madonna and Child by Michelino (Pittura a Milano dall'Alto Medioevo al Tardogotico, p. 160):

And this one (p 171):

Is there any other similarity not shared by such as these? Well, here are Benedetto's faces alongside the tarot images:

I don't see much similarity, other than a generic one common to many artists.

So let us turn to the Madonna of Humility. Here it is (http://museolia.spezianet.it/index.php? ... 69&lang=en):

This painting is more of the same. The "particularly curly russet hair" noted by Dummett is prominent on the Christ child in both paintings. But again, they all painted putti and baby Jesuses that way, russet, yellow, or gold: the color is that of the morning sun, appropriate to young children (see Roettgen's book, or Alexander's Italian Renaissance Illuminations); the curls might come from Apollo. (See e.g. the Michelino above.)

However there is one more work that bears inspection, posted by Ross Caldwell on p. 4 of the thread with this title on ATF. He identifies it as "Madonna introno col Bambino," Cremona, Museo Civico, with the link

http://www.alfonsomariadeliguori.ne...IS77IS2006.html:

When I line up Temperance’s face with the Virgin's, I seem to see a resemblance:

And here is the Christ child next to the child on the Sun card:

In these cases there is a three-dimensionality to the figures that is perhaps associated with the "Ferrara" style , even while conforming in outline to Gothic convention. But Adolfo Venturi, writing in 1931, says of this piece, "his methods recall in some degree the earlier works of the Paduan school" (p. 12). It seems to me (as it did to Venturi, p. 12) that this painting was painted later than the Torrechiara of 1462. Here is more of Venturi's analysis:

Venturi goes on to describe the paintings that are on either side of the main scene of this polyptych, of St. George and St. Anthony. Then he returns to the Virgin:The artist strives to impart relief to his figures, and for this purposes emphasizes the shadows on the Virgin's face to such an extent that the whole face appears swollen, while at the same time he tucks her body away into a mantle of gold filegee as though it were a swrod in its scabbord.

Especially note the needle-point pattern of the brocades that he describes, since many of the cards also have such brocades. All in all, the painting is just the thing to use as a model for some trionfi cards! As far as the dating, even if we knew with certainty when it was done, and that it was from the same workshop that did the Temperance card, we still wouldn't know when the card was done: it could have been made any time after the painting, using the preliminary studies, and even by someone else in the workshop. Presumably this painting has always been in Cremona (who else would want it?). If so, the person commissioining the cards could have just said, "Make her like in that painting."The drawing of the contours, especially in the case of the Virgin, the angels perched on the throne and the rugged St. George, is crude and stiff; the types are devoid of grace, with puffy cheeks, bulging foreheads and small features; the patterns on the brocades are put in with a sort of mechanical precision that might have been achieved with the point of a needle.

But did that painting in particular have to be the model? Well, whoever did the cards knew his International Gothic but also learned from Padua or Ferrara. The three-dimensionality is evident in the folds of the Temperance lady's dress and in the skin of the putti of the Sun and World cards. Yet while the resemblance between card and painting is impressive, the resembling features are fairly standard.

To get a better match I would add one more variable. That is, the artist might have been asked not only to paint the cards like the painting, but also to paint it like certain family members. So instead of just looking like the Madonna of Humility, she also has to look like Elisabetta Maria Sforza, as I have suggested in earlier posts. But what did Elisabetta look like? All I have to go on is Vogt-Leuerssen's speculation (kleio.com). While some of her claims are difficult to sustain, that isn’t true of all of them. The front-view she uses for Elisabetta is from the altarpiece at Treviglio Cathedral, done around 1485 by Bernardo Zenale and Bernardino Butinone (http://bode.diee.unica.it/~giua/SEBASTIAN/). She is the lady on the right:

This altarpiece is too late for our card, of course, but they might have worked from likenesses done earlier and now lost. Moreover, Butinone may even have worked for Bembo. Venturi notes that in the St. Anthony of the Cremona polyptych "we seem to find a forerunner of the figures painted by Butinone." (p. 12) One of Venturi's descriptions of Benedetto's Virgin's would apply even more to Butinone's females: "haughty, bloated, with a small inquisitive nose and a mouth like a rosebud" (p. 12). The best example is Butinoni's altarpiece at the Palazzo Borromeo (Venturi plate 15), a place already known to tarot buffs as the scene of the "tarocchi players" fresco.

Both the Virgin and the saint to the right compare to the figure in the Treiglio altarpiece. The other ladies in the Treviglio altarpiece certainly do look like other likenesses identified with Bona and Ippolita. Here is the face that Vogt-Leuerssn identifies with Elisabetta, added to the ones I showed before, from the cards and the Cremona Enthroned Madonna:

Last edited by mikeh on 01 Oct 2014, 01:18, edited 1 time in total.

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

69http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/ ... uster.html

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/sfor ... ction.html

http://www.faksimile.ch/werke/werk.php?l=e&show=2&nr=46

http://www.lesenluminures.com/media/pre ... 3oct04.pdf

I've not much time and the computer is broken for the moment. The situation of the Medici heraldic is general not satisfying, as we have only snippets of art historians, who occasionally say a few words to the heraldic.

http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/ttp/sfor ... ction.html

http://www.faksimile.ch/werke/werk.php?l=e&show=2&nr=46

http://www.lesenluminures.com/media/pre ... 3oct04.pdf

I've not much time and the computer is broken for the moment. The situation of the Medici heraldic is general not satisfying, as we have only snippets of art historians, who occasionally say a few words to the heraldic.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: "The 5x14 Theory: An Investigation" part II

70Thanks for the links, Huck. They put a different perspective on the missing pages in the Sforza Hours. The 1894 editor does talk about the theft, as the artist's letter had been published in the Archivio Storico Lombardo for 1885, p. 541 ("in one of a series of valuable articles on 'L'arte del minio nel ducato di Milano,' compiled by G. Mongeri from notes of the Marchese Girolemo d'Adda"). But he interprets the artist as saying that the stolen pages had been recovered, by another friar who bought the material from the first friar and then turned it over to "Monsignor Juan Maria Sforzino," i.e. Giovanni Maria Sforza, half-brother of the duke, who in 1498 would become Archbishop of Genoa. The artist asks his sovereign (probably Ludovico) not to release the thief until he gives up the 500 ducats that these pages (a third of the total) are worth, to pay the artist. He also needed to be paid the "stipulated" 1220 "libre" for the main part of his work that hadn't been stolen. The 1894 editor observes that the 500 ducat valuation was the artist's, not Bona's, just as the 100 ducats for "Virgin of the Rocks" (per a document published 1894) was Leonardo's.

I surmise that later scholars, with more information, decided that the best explanation of the missing pages is that not all the stolen work had been recovered, and that in particular the miniatures were still missing. I still wonder how the artist could have been given such a wrong impression, since those miniatures (12 or 16 out of 64 total miniatures) were the most valuable part of the stolen material. Maybe the 1894 editor misread the letter, and it didn't say that the material had been recovered. I'd like to know more, but it's not important for our purposes.

I found the reference that I had thought said the phoenix was a Savoy device. It actually said that the phoenix was Bona's personal device ("A Sforza Miniature by Cristoforo da Preda," by Michal A. Jacobsen, vol. 116 (1974), p. 91ff). He does not comment on whether it was a Savoy device. On Bona's personal devices, he cites the same 1894 book that I have been citing, as well as F. Malaguzzi-Valeri, La Corte, Vol. III, p. 157, and G. Clausse: Les Sforza et les arts en Milanais, p. 94). Jacobsen;s example of Bona's phoenix is in the picture of Galeazzo praying that I posted a detail of earlier, from Kaplan's Vol. 2. The bird is in the lower left. Here is the relevant detail:

vol. 116 (1974), p. 91ff). He does not comment on whether it was a Savoy device. On Bona's personal devices, he cites the same 1894 book that I have been citing, as well as F. Malaguzzi-Valeri, La Corte, Vol. III, p. 157, and G. Clausse: Les Sforza et les arts en Milanais, p. 94). Jacobsen;s example of Bona's phoenix is in the picture of Galeazzo praying that I posted a detail of earlier, from Kaplan's Vol. 2. The bird is in the lower left. Here is the relevant detail:

The miniature itself was apparently done in April of 1477 and reflects an actual military campaign that Galeazzo led during the autumn of 1476, to free Savoy and Bona's imprisoned sister-in-law from the Burgundians. Contingents from the Bentivoglio of Bologna and the Ganzagas of Mantua joined him. With the onset of winter, both Charles' activity in Piedmont and Galeazzo's ended, but "evidently not before Galeazzo had the best of the fighting," the author says. Galeazzo was assassinated a few weeks later. Jacobsen adds: "Probably the manuscript was ordered by Galeazzo himself but completed after his death upon the instructions of Bona." The text accompanying the illumination is missing, but Jacobsen proposes that it is the psalm beginning "Ad te, Domne, levavi animam meaum" (Unto thee, O Lord, I lift up my soul), the subject of which was "Let not mine enemies triumph over me." Jacobsen observes that "Galeazzo's pose in this illumination was derived from images of King David kneeling in prayer commonly found in initial letters of this very psalm." The illumination forms the letter "A," the first letter of the psalm. The towers are the side, the foliage the top, and the stream running next to the troops is the crossbar.

Lest this point seem stretched, the author shows a similar design, with the text of the psalm attached, in a Hungarian miniature that he argues was inspired by this one; he hypothesizes that a copy of the manuscript was sent to Matthias as part of the engagement of the young Bianca to him. He notes that Galeazzo's portrayal as David, while apparently unique, is typical not only of the Sforzas but the Viscontis before them, back to the first duke. Scholars have been pointing out examples of such apparent self-representation since at least 1963, several of which Jacobsen cites.

Now, Huck, here are some thoughts about some of your remarks on other subjects:

(1) If the thinner gold paint lasts longer, and it was used in the added PMB cards either later than the paint used in the original PMB or by a different workshop, what does that say about the Brera-Brambilla? I have not seen the actual cards, but from photos and people's reports, they really glisten, compared with the CY and the PMB, and close in shine to the Charles VI and some of the PMB-style partial decks. For color photos of examples see http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_ ... ID=5148235.

The Brera-Brambilla would seem, then, to have been done around the time and/or in the workshop of the added PMB cards. We cannot go by clothing and painting styles, because the Sforzas, until Ludovico, deliberately promoted a connection to the Viscontis before them. As Luke Syson observes in his article “Leonardo and Leonardism in Sforza Milan, “It is well known that Both Francesco Sforza and his eldest son and successor were keen to emphasize a dubious continuity with the earlier Visconti regime” (Artists at Court: Image-Making and Identity, 1300-1550, p. 107). This quote is in the context of explaining why the style of the frescoes at the Pavia castello was so conservative, as well as Gian Galeazzo’s commissions at the Certosa.

Another point is that the Sforzas deliberately discouraged individual styles in their artists, so that “credit for the magnificence of these works would fall squarely on the shoulders of the patron” (Syson p. 107). For major projects, responsibility did not even fall to a particular workshop: painters “traditionally formed ad hoc teams to undertake particular projects, for which they would bid as a team.” Thus “one Lombard painter might adopt the motifs and working methods from another, without that latter artist having necessarily been his master.” So when art historians such as Venturi say that one part of a polyptych credited to Benedetto Bembo looks similar to the later work of another artist, that suggests to me the probability of joint work of the two artists on the earlier work, without the two having to be part of the same shop.

(2) I have been examining Madonnas in Ferrara (by e.g. Tura, del Cossa, and the miniaturists Giraldi and Crivelli) to see if any resemble the PMB lady of the second artist. I find the receding hairline, but not the pursed lips.

(3) I have been looking at male figures, too, in hopes of getting more clarity about the man on the Fortitude card. I know that some people, including me, identify him with Francesco Sforza, but the image doesn't correspond to Francesco's portraits. I noticed a nice portrait of Borso and thought I detected a resemblance to the lion-beater:

Another portrait, showing him older, is at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borso_d%27 ... of_Ferrara. Could the PMB Fortitude be a portrait of Borso as Hercules? If so, I wouldn't think that it was done during Borso's lifetime. According to Wikipedia in the article just cited, Borso and Francesco were not on friendly terms. Here is Wikipedia:

However Galeazzo could have wanted a deliberate resemblance to Borso after his death in 1471, as a gesture of goodwill to Ercole (communicated through emissaries) and a tribute to Borso and Francesco both. In fact, as I understand it, Ercole did ally Ferrara with Milan after Milan helped in Ferrara’s 1482-1484 war against Venice (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_Ferrara). I am acknowledging your point about how the Hercules legend was adopted by the d'Estes, but still coming to my conclusion rather than yours, that the card was probably Galeazzo's late idea.

I surmise that later scholars, with more information, decided that the best explanation of the missing pages is that not all the stolen work had been recovered, and that in particular the miniatures were still missing. I still wonder how the artist could have been given such a wrong impression, since those miniatures (12 or 16 out of 64 total miniatures) were the most valuable part of the stolen material. Maybe the 1894 editor misread the letter, and it didn't say that the material had been recovered. I'd like to know more, but it's not important for our purposes.

I found the reference that I had thought said the phoenix was a Savoy device. It actually said that the phoenix was Bona's personal device ("A Sforza Miniature by Cristoforo da Preda," by Michal A. Jacobsen,

The miniature itself was apparently done in April of 1477 and reflects an actual military campaign that Galeazzo led during the autumn of 1476, to free Savoy and Bona's imprisoned sister-in-law from the Burgundians. Contingents from the Bentivoglio of Bologna and the Ganzagas of Mantua joined him. With the onset of winter, both Charles' activity in Piedmont and Galeazzo's ended, but "evidently not before Galeazzo had the best of the fighting," the author says. Galeazzo was assassinated a few weeks later. Jacobsen adds: "Probably the manuscript was ordered by Galeazzo himself but completed after his death upon the instructions of Bona." The text accompanying the illumination is missing, but Jacobsen proposes that it is the psalm beginning "Ad te, Domne, levavi animam meaum" (Unto thee, O Lord, I lift up my soul), the subject of which was "Let not mine enemies triumph over me." Jacobsen observes that "Galeazzo's pose in this illumination was derived from images of King David kneeling in prayer commonly found in initial letters of this very psalm." The illumination forms the letter "A," the first letter of the psalm. The towers are the side, the foliage the top, and the stream running next to the troops is the crossbar.

Lest this point seem stretched, the author shows a similar design, with the text of the psalm attached, in a Hungarian miniature that he argues was inspired by this one; he hypothesizes that a copy of the manuscript was sent to Matthias as part of the engagement of the young Bianca to him. He notes that Galeazzo's portrayal as David, while apparently unique, is typical not only of the Sforzas but the Viscontis before them, back to the first duke. Scholars have been pointing out examples of such apparent self-representation since at least 1963, several of which Jacobsen cites.

Now, Huck, here are some thoughts about some of your remarks on other subjects:

(1) If the thinner gold paint lasts longer, and it was used in the added PMB cards either later than the paint used in the original PMB or by a different workshop, what does that say about the Brera-Brambilla? I have not seen the actual cards, but from photos and people's reports, they really glisten, compared with the CY and the PMB, and close in shine to the Charles VI and some of the PMB-style partial decks. For color photos of examples see http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_ ... ID=5148235.

The Brera-Brambilla would seem, then, to have been done around the time and/or in the workshop of the added PMB cards. We cannot go by clothing and painting styles, because the Sforzas, until Ludovico, deliberately promoted a connection to the Viscontis before them. As Luke Syson observes in his article “Leonardo and Leonardism in Sforza Milan, “It is well known that Both Francesco Sforza and his eldest son and successor were keen to emphasize a dubious continuity with the earlier Visconti regime” (Artists at Court: Image-Making and Identity, 1300-1550, p. 107). This quote is in the context of explaining why the style of the frescoes at the Pavia castello was so conservative, as well as Gian Galeazzo’s commissions at the Certosa.

Another point is that the Sforzas deliberately discouraged individual styles in their artists, so that “credit for the magnificence of these works would fall squarely on the shoulders of the patron” (Syson p. 107). For major projects, responsibility did not even fall to a particular workshop: painters “traditionally formed ad hoc teams to undertake particular projects, for which they would bid as a team.” Thus “one Lombard painter might adopt the motifs and working methods from another, without that latter artist having necessarily been his master.” So when art historians such as Venturi say that one part of a polyptych credited to Benedetto Bembo looks similar to the later work of another artist, that suggests to me the probability of joint work of the two artists on the earlier work, without the two having to be part of the same shop.

(2) I have been examining Madonnas in Ferrara (by e.g. Tura, del Cossa, and the miniaturists Giraldi and Crivelli) to see if any resemble the PMB lady of the second artist. I find the receding hairline, but not the pursed lips.

(3) I have been looking at male figures, too, in hopes of getting more clarity about the man on the Fortitude card. I know that some people, including me, identify him with Francesco Sforza, but the image doesn't correspond to Francesco's portraits. I noticed a nice portrait of Borso and thought I detected a resemblance to the lion-beater:

Another portrait, showing him older, is at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borso_d%27 ... of_Ferrara. Could the PMB Fortitude be a portrait of Borso as Hercules? If so, I wouldn't think that it was done during Borso's lifetime. According to Wikipedia in the article just cited, Borso and Francesco were not on friendly terms. Here is Wikipedia:

That battle was in 1467 (http://www.comune.molinella.bo.it/model ... aspx?ID=71). This animosity presents a problem for your idea that Borso was familiar with the PMB cards, so correct me if Wikipedia is wrong.He was generally allied with the Republic of Venice, and enemy both to Francesco I Sforza and the Medici family. These rivalries led to the indecisive Battle of Molinella.

However Galeazzo could have wanted a deliberate resemblance to Borso after his death in 1471, as a gesture of goodwill to Ercole (communicated through emissaries) and a tribute to Borso and Francesco both. In fact, as I understand it, Ercole did ally Ferrara with Milan after Milan helped in Ferrara’s 1482-1484 war against Venice (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/War_of_Ferrara). I am acknowledging your point about how the Hercules legend was adopted by the d'Estes, but still coming to my conclusion rather than yours, that the card was probably Galeazzo's late idea.