Ross and Huck,

Thank you both for fleshing out more details about Agnese.

Ross G. R. Caldwell wrote: 31 Mar 2020, 15:11

The name of Agnese's grandfather in Motta's genealogy above must be

Andreotto, since he is named among the

Consiglio Generale or

Consiglio dei Novecento in 1388, the full list of which is given in Felice Calvi,

Il patriziato milanese (1875), p. 380, as one of those from the Porta Vercellina, Parrochia Monasterii Novi, as

Andriotus de Mayno.

https://books.google.fr/books?id=d1fkGQ ... &q&f=false

That was a family name, so makes sense: Agnese's brothers were a Andreotto and Lancillotto, the former playing a formative roll in Galeazzo Maria's upbringing (e.g., he accompanied the young prince to Ferrara in 1457 where we encounter the water-borne

trionfi and the 70 card deck).

We even find this uncle of Bianca in a sot of exchequer role for her (machine translations follow):

When it came to honoring the commitments made by Bianca Maria, Andreotto Del Maino had a list made based on the testimonies of his collaborators ...Among the most consistent items were the promises made to individual people of his entourage and to some Milanese and Cremonese monasteries particularly dear to the Sforza: the friars of the Incoronata [the double church built in 1451 near the gate to Como], the female Augustinian monastery of Sant'Agnese and the nuns of San Benedetto di Cremona. Other promises were claimed by his doctors, in particular by Christopher da Soncino and Benedetto Reguardati, whose son had married a Del Maino. Maria Nadia Covini, Donne, Emozioni E Potere Alla Corte Degli Sforza 2012: 35).

Naturally you'll be interested by Bianca's interest in a church of her mother's namesake (interesting, again, in the light of the Vesta-Agnese connection going back to Saint Ambrose and noted here as a female monastery in keeping with Marziano's description of Vesta). But moving on with Andreotto....

Eventually, apparently Galeazzo Maria tired of his uncle chaperone, after Francesco's death due to squabbling over various fiefs, etc.:

One of the points of friction with the Sforza was the marriage of Count Pietro. Since the 1950s the countess had engaged in a marriage to the lord of

Faenza, his relative, but had been opposed by Francesco Sforza29. Yes, I speak then of the marriage between Pietro and a daughter of Roberto Sanseverino and then the long story of the marriage with Cecilia by Andreotto del Maino began, complicated by dowry and property matters, an inextricable tangle that complicated further when Galeazzo Maria Sforza became duke and took attitudes hostile towards the Del Maino and towards the whole entourage of the mother.(ibid, 98)

And yet I wonder how the father, Francesco Sforza, viewed the Del Maino? As a faction that was key to his gaining Pavia in 1447 they were pivotal to his rise in Milan, where presumably they used all of their connections to get the other elites, especially the "Ghibellines", to his side (certainly this is what Covini lays out for Agnese for her son-in-law). The Pisanello medal of 1441 makes clear he was granted and readily adopted the Visconti name....but did he do something in recognition of his mother's family as well, restored to positions of relative power by the 1440s at least?

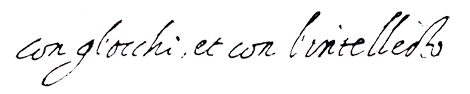

Consider Sforza's obscure greyhound beneath the pine tree impresa in this context, sometimes with a divine hand reaching out of a nimbus cloud above it. Although a lead goes from the tree to a collar, the greyhound is always shown without the collar, it laying on the ground. The literature pretty much all relies on Bernardino Corio's

Storia di Milano, as does Carlo Maspoli in his explication of this

impresa in his

Stemmario Trivulziano:

The impresa of the dog sitting under the pine with his celestial hand, dates back to the Visconti period, as we find it carved with his motto on a scroll held by one of the female figures placed on the sides of the equestrian statue of the sarcophagus of Bernabo Visconti already in S. Giovanni in Conca and now kept in a room in the castle of Milan; this undertaking is linked to the singular figure of Bernabo Visconti, who was surely the most passionate hunter of all the principles of his family, so much so that for his hunting preference, in particular for the wild boar, he had a large crowd of five thousand dogs, entrusted in custody to that part of his subjects who had an estimate of at least five hundred imperial lire. All those who kept one of these dogs were obliged, twice a month, to have it checked, and as Bernardino Corio reports in the History of Milan "in order to find macri [? no translation], they were charged with large sums of money, and if they were rich, blaming them for too much, they were similarly beaten; if they [dogs] died he took it all; and the officials of the hounds were more feared than the praetors of the lands." The celestial hand, emerging from a nimbus, which accompanies the dog (greyhound of “leviere”[? a different dog breed]) seated under the pine, and generally placed high on the right of the beholder, and sometimes he holds the dog by the leash and twisted around the pine stem. The impresa is associated with the Quietum Nemo Impune Lacesset ("no one will ignore peace with impunity"); "Even if at rest no one will tie him with impunity"; "No one will cause peace"), a motto that can be reflected in the saying "do not tease the sleeping dog" [let sleeping dogs lie].

This undertaking, with an explicit meaning and aided by the clear motto, was dear to Francesco I Sforza, who thus warned that, by not harassing anyone, he could not bear to give it to him, being ready otherwise to react to the provocation

In the main altarpiece of the Sigismondo Abbey in Cremona, by Giulio Campi, the Duke Francesco I Sforza and Bianca Maria Visconti are represented: here their wedding was celebrated on 25 October 1441; the choice of this church at the time in the open countryside was dictated by a precautionary measure decided by the spouse afraid of some plot by the treacherous father of the bride Filippo Maria Visconti, third duke and last representative of the Visconti lordship over Milan. The valuable painting, in addition to representing a historical fact, is an important document for the heraldist, since in the military day of Francesco I Sforza the impresa of the dog sitting on the pine tree and with a heavenly hand was finely embroidered, an enterprise quartered with that of the wave.

(2000: 39-40, my tweaked machine translation).

I have long suspected the PMB Just and Fortitude trumps - both virtues featuring an armored man like Bernardo Visconti, who is flanked by only those two virtues - referenced this equestrian statue; the fact that Sforza took the dog impresa from this statue's Fortitude (on that flanking virtue's scroll - see further below) and from nowhere else, confirms the importance of this statue for Sforza. Ross's identification of the d'Abano astrological degree decan behind the Fortitude motif - the 26th degree of Libra as "Victor Belli", The Victor in War. - merely underscores that Sforza is using it beating an enemy (the lion must be a symbol of the enemy: Venice, symbolized by the lion of St. Mark).

What is interesting is that F. Sforza was depicted in this impresa in his wedding church - does that echo the symbolism of the CY love trump, which also features a greyhound? What is clearly wrong in that late painting, however, is showing the dog with the collar on. What Maspoli might have mentioned is the large format depiction of this impresa opens up the astrological work

de Sphaera produced for Sforza during his lifetime. What is interesting is how the umbrella pine so perfectly matches the shape of the matrimonial tent in the CY Love card, also featuring a white greyhound, at the base of the pole/tree in each case:

And what of the Del Maino? The greyhound was their stemma, per the Stemmario Trivulziano (Mayno there) produced under Sforza. The greyhound in the CY Love card wears a collar as does the Del Maino dog - something never done with Sforza's impresa, although it is shown on Bernado's equestrian statue prototype with a collar. Sforza's court then invented a more menacing version of the impresa - unleashed and ready for vengeance (in keeping with the violently active portrayal of Fortitude in the PMB) . It took me a good deal of searching but I finally found an image of the faintly inscribed (like a cartoon) dog under a pine on Fortitude’s scroll, on a webpage dedicated to the restoration efforts regarding this statue:

https://www.nicolarestauri.org/en/rest ... sconti-165

We then have the possibility that the greyhound in the CY Love is not random "filler", but speaks to the bride's own lineage, maternally descended from an important Milanese family, that went back to the time of Bernardo Visconti (and as Ross noticed, at least among the duchy’s

Consiglio Generale or

Consiglio dei Novecento ...and certainly important enough to participate in a coup of sorts in the assassination of Giovanni Maria). Whether Bernardo loaned the use of the greyhound

impresa to the Del Maino is unknown, but that would be similar to the loaned use of the three ring device among the d'Este, Sforza, Borromeo and Medici, also with variations. In that context note that the singular ring originally allowed for use by Muzio Sforza is held by the dragon-old man (Saturn/time, in connection with a remembrance of the father?) to the right of the dog/pine motif on the

de sphaera illumination. Aware of the dog at least since his wedding to a Visconti-Del Maino, once Sforza took Milan he presumably adopted the

impresa for himself, connecting himself to the illustrious and most feared militant of all the Visocnti – Bernardo – a connection his wife’s family already had. I would also note if the greyhound in the CY Love card is a reference to Bianca's maternal Del Maino relations' heraldic identifier (naturally below the Visconti

biscione pennants flying above, as does Pavia's stemma to which the Del Maino helped Sforza to), the faithful Del Maino dog is leading Sforza to the bride (and the dog is not "rampant" as on their

stemma, as that would of course been uncouth for a dog to be leaping onto a bride). As a heraldic symbol, the dog would have had a double entendre meaning for Sfora, as it were.

Below, the

Mayno stemma in the

Stemmario, details of the dog from the CY love and Bernardo's

impresa upon Fortitude’s scroll from his equestrian statue.

Phaeded