***********- .... 5 molds with "4x4 cards = 16 cards" would make 5x16 cards = 80 and that would be enough for a Taraux deck with 78 normal cards + 2 additional cards with unknown function. Naturally the 5 molds might have had also other function, not related to the Taraux production.

- .... 288 normal decks either made in Lyon or made also in Avignon in Lyonaise style, possibly with molds bought in Lyon

- .... 48 decks of Taraux cards

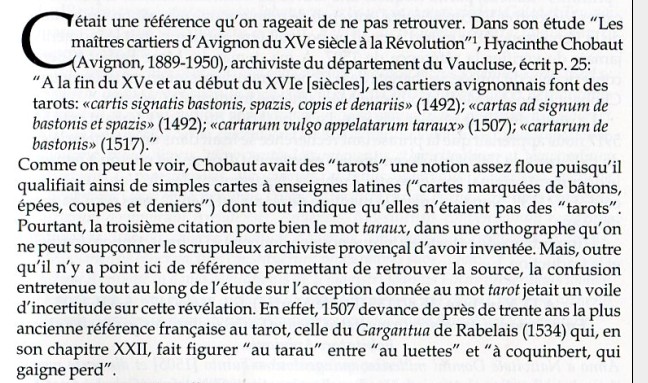

The 2004 article of Depaulis to the researcher Chobaut (1955) and his errors about Tarot cards in Avignon, which finally led to the recognition of the Avignon document of December 1505 (Chobaut had given it to 1507).

Chobaut had identified the production of cards with Italians suits in Avignon as production of "Tarot cards". At least we know from this, that cards with Italian style occasionally were produced in Avignon (since 1492) ... rather precisely the time, when cardinal Guiliano de Rovere (later pope Julius II) preferred to take his place in France, cause he feared the mighty hands of pope Alexander VI.

Once we had this funny thread about Chobaut ...

viewtopic.php?f=11&p=11543#p11543

The Chobaut text is online, but only as snippets ...

https://books.google.de/books?id=Tn4SAA ... edir_esc=y

Ross once gave some summaries of the Chobaut text at the begin of the following thread ...

http://tarotforum.net/showthread.php?t= ... ignon+1505

Interestingly Italians are noted at the begin of the development, not as cardmakers, but possibly as business men interested to establish also a card production.From Hyacinthe Chobaut, "Les maîtres-cartiers d'Avignon" (Provence Historique, t. VI (1955), pp. 5-84).

Earliest mention of cards is 15 January, 1431.

Bernard de Guillermont, papermaker, agrees to sell all of his paper for the upcoming year at a fixed price to two Italians established at Avignon (Nicolas de Ambrosiis and Odet Bouscarle), all kinds of paper including paper for making playing cards - "pro qualibet rayma papiri ad faciendum cartas pro ludendo, viginti unius grossorum" - for any ream of paper for making playing cards, twenty-one gross.

14 October, 1437. A certain Jaco Sextorii, papermaker, sells his production of paper for one year to the Italian Odet Bouscarle - all types of paper including paper "pro rayma papiri dupli pro cartis, viginti grossorum" - for a ream of double paper for cards, twenty gross. (the name is shorter (cartis) and the price is going down!)

Chobaut notes that paper-making in the Comtat-Venaissin (Avignon region) begins in the second half of the 14th century. He says that while some of this paper might have been made for export to towns like Lyon, it is highly probable that there were already card-makers in Avignon.

1441 - card playing prohibited in the Statutes of Avignon for religious and clerics. - "... statuimus et ordinamus, quod si quis clericus vel ecclesiastica persona ad ludos taxillorum, alearum vel cartarum publice vel occulte ... ludere praesumbit".

1441, 8 May. Etienne Mouret or Moret, named "factor cardarum (=cartarum)" - cardmaker. He is the earliest known cardmaker in Avignon. He is known to have lived in Avignon since 12 March, 1419 to around 1435, when he had moved 24km from the town (from 1419-1437, he is called "mercier" (haberdasher) in various documents; he is called "painter" in a document of 1437, and then in 1439 he moved to Avignon again, where he is called "mercier" in two documents of 1439 and 1440. In 1441 he is called "cardmaker" for the first time).

1442, 30 April. Mouret again named "factor cartarum".

1443, 15 June. Mouret again named "factor cartarum".

1443, 4 December. Mouret called "factor cartarum et pictor" (cardmaker and painter). This is the last time he is named in Avignon. Chobaut writes that "I believe that Mouret was a mercier, painter and cardmaker at the same time. These three professions were related in the 15th century (...). It must not be forgotten that at this time merciers sold playing cards, and that they were often painted by hand." (Marchione Burdochio (Bolognese) in Ferrara at the same time was a mercier (merzaro), and sold triumph cards to the Este family). Chobaut continues - "Even though we do not find him called specifically a cardmaker until 1441-1442, nothing prevents thinking he exercised this profession beforehand."

1444-1448. Mouret lives in Montpellier. In 1447 a certain Pierre Mouret, perhaps Etienne's son, is described as "fazedor de cartas, alias de ybys, que demora sota 'Sant Nicolau'" - cardmaker, also called 'ybys' (=naybes?), who lives under 'Saint Nicholas'". In 1448 Etienne Mouret is described as someone "que fa las cartas ho lo ybes per joguar" - who makes cards or 'ybes' for playing.

1441-1448. Gillet Curier is the second known cardmaker in Avignon. He is alternately called mercier and cardmaker in the documents; the earliest time he is called "factor cartarum" is 5 January, 1445. He also made images of Saint Peter of Luxemburg for the Celestine monastery of Avignon, perhaps for sale to pilgrims.

1448. Jean Benoît (from Bourges) is called "mercier".

1450. Jean Benoît is called "factor cartarum" (third known cardmaker in Avignon).

1451. Jean Benoît is called "factor cartularum".

1451. Jacques Monteil (from du Puy) "factor cartarum".

1456-1480. Raynaud Silvi (from Orpierre in diocese of Gap), named "factor cartarum" in various documents (fourth known cardmaker in Avignon).

1459-1472. Antoine Biolet, (originally from Lyon), named "carterius", "factor cartarum", or "factor quartarum" in various documents (fifth known cardmaker in Avignon).

1463. A certain "Labe" and Richard Rétif, named "factores cartarum" (sixth and seventh known cardmakers in Avignon).

1464-1487. Guillaume Veron (from Poitiers), named "factor cartarum" (eighth known cardmaker in Avignon).

1469. Guillaume Trentesous, named painter and "faciens cartas ad ludendum" (ninth known cardmaker in Avignon).

Chobaut continues - "Around 1475-1480... the number of master cardmakers multiplies in Avignon. Some learned their craft here, while others came from all over: Jean Barat, from the diocese of Ivrea (1473-1481); Guillaume Bal or Bar, from the diocese of Tarantaise (1485-1502); Jean Janin, from the diocese of Besançon (1477-1485); Antoine Deleuze (de Illiceto), painter and cardmaker, from Fontarèche in the diocese of Uzès (1473-1520), and even a woman, Catherine Auribeau, 'carteria', widow of the master Raynaud Silvi (1480-1510), etc...

"The most important producers of this epoch are : Pierre Perouset, painter decorator, cardmaker and merchant furrier, from Vienne (1481-1506), and Jean Fort or Le Fort (1488-1510), originally from the diocese of Paris, or perhaps earlier from Bernay in the diocese of Lisieux, who each had numerous apprentices. One finds beside them Jean Chaudet, from the diocese of Vienne (1483-1497); Jean Brunet, merchant mercier and cardmaker, from the diocese of Geneva (1481-1498), then his son Jean (1517-1521); Charles Charvin, from the same diocese (1497-1517); Antoine Filhat, originally from the diocese of Belley (1497-1520); Léonard Nicolay, from the diocese of Limoges (1500-1515), etc...

"Many of these specialists probably came from the Lyonnais center, very important for the fabrication of cards in the 15th century. The documents will show us that the production of cards was very abundant in Avignon between 1480 and 1515, even if, - to my knowledge at least, - no playing card preserved today in either public or private collections today is witness of it."

(pp. 9-10).

1505. December. The first known reference anywhere to cards called "taraux" (a little earlier in the year, in Ferrara, "tarocchi" are mentioned for the first time). Cardmaker Jean Fort (mentioned above), in Avignon, agrees to send various items to Pinerolo (in Savoy/Piedmont, near Turin), including 48 packs of cards "commonly called taraux".

Chobaut - "This period of prosperity (for the Avignonnais cardmakers) ceased between 1510 and 1520. Already in 1506, Pierre Perouset had gone bankrupt, his possessions were sold; beginning in 1510 Jean Fort abandonned the profession of cardmaker to devote himself entirely to haberdashery; some masters equally gave themselves over to other activities; many left Avignon, which they abandonned no doubt to find their fortune in other towns."

This abrupt decline was no doubt due to the massive production in Lyon.

The name "Fort" (the producer of 1505) appears variously. The last passage (by Ross) describes the decline of card production in Avignon ... which - according my suspicion in contrast to the interpretation of Ross ("This abrupt decline was no doubt due to the massive production in Lyon.") - has something to do with the condition, that pope Julius had left Avignon and in the following years the relation between France and Julius declined, too.

On archbishop in Avignon Giuliano de Rovere (= Pope Julius II) followed ...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Cat ... of_Avignon

The 3 last of these surely weren't much in Avignon.1474–1503: Giuliano della Rovere (Archbishop from 1475)

1504–1512: Antoine Florès

(rather unknown)

1512–1517: Orlando Carretto della Rovere (Orland de Roure) ... parallel to pope Julius II (died 1513), also Rovere

http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/bishop/brovo.html

1517–1535: Hippolyte de' Medici ... parallel to the both Medici popes, himself the illegitimate son of Clemems VII

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ippolito_de%27_Medici

1535–1551: Alessandro Farnese the Younger ... parallel to the Farnese pope Paul

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alessandr ... (cardinal)

****************

Reading the Depaulis article again, I'm puzzled about a "9" as the difference between "34" and "45" (likely a typo or I don't understand something ... it should be 11).

A paper merchant (Chistoforus Galea) and a card producer (Bernardin Truque) are at the habitation of Joanni Fortis in Avignon and trade paper in the value of 45 Florins of Avignon currency to 34 Florins of Avignon currency and the mentioned items (5 moles, 288 decks from Lyon, 48 Taraux card decks and 3 books of special quality). Galea and Truque are both from the discussed location Pinerolo. The action needs a notary and a witness.

No word, what motifs were on the "moles" or moulds (Tarot or other playing cards; I can't imagine,that they were empty).