NOTE ADDED JULY 3: I CHANGED THE TITLE OF THE THREAD BY ADDING "& MORE". THAT IS BECAUSE I WANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE THAT POSTS HERE DO NOT ALWAYS HAVE TO COMMENT ON DUMMETT'S BOOK. THEY CAN COMMENT ON THINGS IN OTHER PEOPLE'S COMMENTS, NOT DIRECTLY RELATED. THEN IF THE DISCUSSION KEEPS GOING, ANOTHER THREAD MIGHT BE APPROPRIATE. THIS HAS HAPPENED STARTING AT THE TOP OF P. 6 OF THIS THREAD, CONTINUING ON P. 7; IT IS A GOOD DISCUSSION OF MARCELLO'S LETTER OF 1449 WITH NEW INFORMATION BUT NOT RELATING TO DUMMETT DIRECTLY. THEN A NEW THREAD WAS CREATED, TO WHICH I HAVE ADDED A LINK AT THE RELEVANT POINT. SINCE DUMMETT'S BOOK INCLUDES MUCH OF WHAT WE TALK ABOUT AS TAROT HISTORY--MORE SO THAN HIS OTHER BOOKS, I THINK--IT SEEMS APPROPRIATE TO RAISE ISSUES HERE RELATED TO OTHER POSTS BUT ONLY VAGUELY RELATED TO THE BOOK.

So I have been reading Dummett's Il Mondo e l'Angelo, translating as I go. My aim is to see what is in this later work (1993) that wasn't in Game of Tarot (GOT) (1980) and to get myself "up to speed", so to speak, with the literature. Since the 1993 work is not available in translation, and hard to get even in Italian, people on this Forum might be interested what is new in that book, not stated earlier. I will go chapter by chapter, and try to fill in as needed the background from 1980. I am mostly trying to "expose" him in the sense of making his later thoughts known. But where I have important disagreements, I will say so. Since I am not an expert translator (I have never studied Italian, just French and Spanish), I include Dummett's relatively easy Italian for reference.

Chapter One is about suits, normal (i.e. without the triumphs) vs. tarot. It recaps the first three chapters of GOT, but omitting all inessentials, including playing cards before they reached the Malmuks and other Mediterranean area Muslims, from whom they entered Europe. I see three additions:

(1) In previous writings, he had made the presence of a Queen in an incomplete surviving deck a strong indicator that the deck is a tarot, because normal Italian decks didn't usually have Queens. His reasoning was that all the normal decks that have survived lack Queens; but since other countries did have such decks--German decks, before 1500, and French suits, from whenever French suits were invented--probably a few in Italy did as well, until after 1500. On this point he now cites two early documents that "suggest" [suggerita] by "hints" [accenni] Queens in normal decks (p. 21).

Here is footnote 5:È tuttavia possibile che fossero occasionalmente usati nell’Italia del XV secolo mazzi normali contenenti le stesse quattro figure del mazzo dei tarocchi; anche

se nessuna carta ci è pervenuta a sostegno di questa ipotesi, essa è suggerita da due accenni in documenti (5).

(However it is possible that there occasionally were used in Italy of the XV century normal decks containing the same four figures as tarocchi deck; even if no card has come down to us to sustain this hypothesis, it is suggested by two hints in documents (5)

In these quotes, I think he means, "regum" means "king" and "regina" means "queen". These hints do not, however, prevent him later on from using Queens as a likely indicator that a deck is a tarot. I will get back to this point later in this post.5. Marzio Galeotti di Nami (morto nei 1478) usa l’espressione l’espressione «regum reginarum equitum peditumque potentiam», senza far cenno ai triumphi, in un passo relativo alle carte da gioco (De doctrine, promiscua, Firenze, 1548, cap. 36 in fondo). Analogamente, San Bernardino da Siena, nel suo sermone contro il gioco d’azzardo («contra alearum ludos») predicato nel 1423, nomina, a proposito delle carte da gioco, per primi «reges atque reginae» e poi « milites superiores et inferiores», ancora una volta senza alcun accenno a triumphi si veda S. Bernardini Senensis O.F.M. Opera Omnia, a cura dei PP. Collegii S. Bonaventurae, Vol. II, Firenze, 1950, Sermo 42, p. 23. È ovviamente possibile che l’uno o l’altro dei due autori avesse in mente le carte da tarocchi, ma non vedesse ragione di nominare i trionfi; questa è, tuttavia, un’ipotesi poco probabile.

(5. Marzio Galeotti di Narni (died in 1478) uses the expression "regum reginarum equitum peditumque potentiam," without mentioning the triumphi, in a passage relating to playing cards (De doctrina promiscuo, Florence, 1548, ch. 36 at the bottom). Similarly, San Bernardino of Siena, in his sermon against gambling (‘contra alearum Ludos’) preached in 1423, names in passing some playing cards, first "reges atque reginae" and then "milites superiores et inferiores', again with no mention of triumphi. See S. Bernardini Senensis, Opera Omnia, edited by PP. Collegii S. Bonaventurae, Vol II, Florence, 1950, Sermo 42, p. 23. It is of course possible that one or other of the two authors had in mind tarot cards, but did not see any reason to name the triumphs; this is, however, an unlikely hypothesis.)

(2) He revises his estimate of when French suits were invented, from about 1480 in GOT to "probably not earlier than 1465" [probabilemente non è anteriore al 1465"] in 1993 (pp. 34f). In his footnote to that remark, he gives his reasoning:

So he is saying that French suits not only probably didn't exist before 1465, but probably did exist by 1470. On p. 47 he is even more precise: the French system "appeared around 1465". His idea is that the French system got the Queen from the German system--as well as adapting the German suit-signs to the greater simplicity of the French. That system didn't become fully developed until "around 1460", he says. The relevance of this point to the tarot will be seen in my point 3 below.20. Un mazzo dipinto a mano del XV secolo, venduto all’asta da Sotheby nel 1984, è probabilmente il più antico mazzo finora pervenutoci di carte da gioco prodotte in o per la Francia. Una descrizione dettagliata del mazzo è nell’articolo di Tom Varekamp, ‘A XV-Century French Pack of Painted Playing Cards with a Hunting Theme’, The Playing Card, Vol. XIV, 1985-6, pp. 36-45 e 68-79. Si tratta di un mazzo completo di cinquantadue carte con segni di seme non standard, tutti collegati alla caccia (comi da caccia, collari di cane, cappi doppi e rotoli di corda). Minuziose ricerche da parte di Varekamp e di altri hanno fissato, per questo mazzo, la data del 1470, con un margine d’errore molto ridotto. La sua importanza per noi è dovuta al fatto che la sua composizione è esattamente quella di un mazzo di semi francesi: ciascun seme ha dieci carte numerali e, come figure. Re, Regina e Fante. Ciò rende probabile, sebbene naturalmente non certo, che il mazzo di semi francesi esistesse già all’epoca in cui questo venne prodotto, perché non si ha notizia di un tale gruppo di figure in alcuna altra forma standard di mazzo normale.

(20. A hand painted pack of the fifteenth century, sold at Sotheby's auction in 1984, is probably the oldest pack of playing cards that has come down produced in or for France thus far. A detailed description of the pack is in the article by Tom Varekamp, 'A fifteenth-Century French Painted Pack of Playing Cards with a Hunting Theme', The Playing Card, Vol XIV, 1985-6, pp. 36-45 and 68-79. It is a full fifty-two card pack with non-standard suit signs, all linked to hunting (hunting horns, dog collars, double knots and coils of rope). Painstaking research by Varekamp and others have set a date of 1470 for this pack, with a very small margin of error. Its importance for us is the fact that its composition is exactly that of a pack of French suits: each suit has ten pip cards and the figures King, Queen and Jack, making it likely, though of course not certain, that the French-suited pack already existed at the time when this was produced, because there is no notice of such a group of figures in any other standard form of normal pack.)

(3) The tarot would not have been commonly known in France until "after the Latin suit system was forgotten over time". First, as in GOT, he says it is a "reasonable assumption" that the Latin suit system was used all over Europe until replaced by other systems in Germany and France. In particular, the French system would have taken over in France very quickly after its invention (p. 38f): it could be produced much more cheaply, needing only stencils for the numeral cards, as opposed to woodblocks. Then he says, (I highlight the most important new inference) (p. 39):

This of course gives him a lead-in for his next chapter, which discusses the earliest extant tarot decks, from Milan. It is also possible that he is providing ammunition for his later contention that the French learned about the tarot from the Italians at the time of their military forays into the Italian peninsula, and not before, i.e. not earlier than 1495.Se il mazzo dei tarocchi fosse stato noto in Francia, Svizzera o Germania al tempo in cui il sistema di semi italiano, o una sua leggera variante, era d’uso comune in quei paesi, i segni di seme usati per i tarocchi avrebbero dovuto seguire la stessa evoluzione di quelli dei mazzi normali: avrebbero dovuto esserci mazzi di tarocchi con semi tedeschi e svizzeri e, già nel Cinquecento, mazzi con semi francesi. Solo se i mazzi dei tarocchi si diffusero in quei paesi quando ormai i segni di seme latini erano stati dimenticati da tempo è possibile spiegare la sopravvivenza di quei segni di seme per le carte da tarocchi in tutta Europa fino alla metà del Settecento.

(If the tarot pack had been known in France, Switzerland, or Germany at the time when the Italian suit-system, or a slight variation, was customary in those countries, the suit signs used by the tarot would have had to follow the same evolution as those of normal packs. There would have been tarot packs in Germany and Switzerland with German and Swiss suit signs, and then, as early as the sixteenth century, with French-suited signs. Only if the tarot packs spread to those countries when the Latin suit signs had already been forgotten over time [erano stati dimenticati da tempo], can the survival of Tarot cards with those suit signs throughout Europe until the mid-eighteenth century be explained.)

In any case, Dummett's point seems to me rather speculative. He gives examples of particular decks surviving because they are attached to a particular game (Aluette is his main example, a "Spanish" deck that survived the commercial onslaught). The tarot deck, with its typically14 cards per suit, quaint designs, and aristocratic pedigree, is for tarot. The French deck of simple suit cards of 13 cards each is for other, more commonplace games.

Another question, for me, is why the tarot, originating in a country where the normal deck usually didn't have Queens, managed so firmly and uniformly to have suits with Queens. I suspect influence from Germany, just as in France. But if so, why not normal decks as well? Here what Dummett says about the putatively 1377 Basel text Tractatus de moribus is relevant, with its discussion of female courts. I highlight the relevant parts in the quote below (although the whole passage is relevant to the issue of Queens) (p. 24f):

However Dummett thinks that a corresponding change did not usually happen to normal decks in Italy, despite his quotes to the contrary from St. Bernardino and Marzio Galeotti di Narni--except in the case of tarot decks, and then always. Dummett's basis is the lack of surviving normal decks with Queens. There are, to be sure, surviving Italian decks that have Queens and no triumphs, but they are "probably" tarots. But there are many more that don't. To evaluate Dummett's claim, I would have to know how many other surviving normal decks contemporary with the tarot decks there are, how many cards are extant in each deck, among other things. He says that surviving hand-painted tarot decks outnumber handpainted normal decks 2 to 1. So there are around 9 without Queens, vs. 2 with and 2 documents. Even if I knew how many cards in each of the nine, and where and when they were from, I have no idea how to compute the odds that the ones without Queens are by chance. I assume he is right. But how did tarots get Queens not normal decks?Il Tractatus de moribus ci è pervenuto solo in un manoscritto del 1429 e in altri tre, tutti del 1472 8. Ci sono pochissime varianti fra questi quattro testi, ma, se l’originale è veramente del 1377, essi devono contenere interpolazioni, forse del copista del 1429. Da questi testi e da un certo numero di antichi mazzi tedeschi pervenutici, veniamo a conoscenza di un alto grado di sperimentazione nella composizione del mazzo normale nella Germania del Quattrocento, e fu in seguito a questi esperimenti che la Regina fece il suo primo ingresso nel mazzo di carte. Ai sostentori della liberazione della donna farà piacere sapere che essa fu originariamente introdotta non come inferiore al Re ma come di pari grado. [/i]Il Tractatus de moribus[/i] descrive mazzi in cui nei quattro semi, o in due su quattro, tutte le figure erano femminili. Un famoso mazzo quattrocentesco dipinto a mano, prodotto fra il 1427 e il 1431, è uno degli esempi a noi pervenuti di questo secondo tipo. In altri mazzi ancora troviamo Unter femminili. Attraverso quella che fu probabilmente una fase di sviluppo successiva, si giunse a mazzi in cui tutti e quattro i semi hanno Re, Regina, Ober e Unter. Esempio di questo è un mazzo dipinto a mano, datato 1440-5, noto come mazzo di caccia Ambraser 9; e ci sono molti altri mazzi tedeschi quattrocenteschi con quattro figure per seme. Il Tractatus non ne fa cenno; esso fa riferimento, tuttavia, con grande entusiasmo, a un tipo che non ci è pervenuto, con quindici carte in ciascuno dei quattro semi, compresi Re, Regina, i due Marescialli e una Servetta (ancilla) come carta più bassa fra le cinque figure. Quando, nel 1470 circa, i fabbricanti di carte francesi introdussero la loro grande innovazione, il sistema di semi francese, essi presero a prestito la Regina dai mazzi tedeschi con quattro figure, in sostituzione del Cavaliere del mazzo con semi latini; fu questa la sua comparsa insieme col Re in un mazzo con solo tre figure per seme.

(The Tractatus de moribus has survived in only one 1429 manuscript and three others all of 1472 (8). There are very few variations among these four texts, but if the original is really in 1377, they must contain interpolations, perhaps by the 1429 copyist. From these texts and a number of old extant German packs, we learn of a high degree of experimentation in the composition of the normal pack in Germany in the fifteenth century, and it was following these experiments that the Queen made her first entry into the card pack. Supporters of women's liberation will be pleased to know that she was not originally introduced as inferior to the King but as of equal rank. The Tractatus de moribus describes packs in whose four suits, or two out of four, all the figures were female. A famous hand-painted fifteenth-century pack, produced between 1427 and 1431, is one example presented to us of this second type. In which feminine Unters are found. Through what was probably a later stage of development, she entered packs in which all four suits have King, Queen, Ober and Unter. An example of this is a hand-painted pack dated 1440-5, known as the Ambraser hunting pack (9); and there are many other fifteenth century German packs with four figures per suit of which the Tractatus makes no mention; it refers, however, with much enthusiasm, to a type that has not survived, with fifteen cards in each of the four suits, including King, Queen, the two marshals and a Servetta (ancilla) as the lowest card among the five figures. When, in 1470, manufacturers of French cards introduced their great innovation, the French suit-system, they borrowed the Queen from German packs with four figures, in place of the Knight in the pack with Latin suits; this was an appearance together with the king in a pack with only three figures per suit.

In the passage I quoted, the parts I highlighted might have a bearing on what city the tarot originated in, or at least acquired Queens in. We know, if nothing else, that tarot decks had Queens. Some had other female courts as well. There was a whole subtype of normal decks, called "Portuguese" that had female pages in two suits. He doesn't say where it originated, except not in Portugal. In the tarot, we find that feature in the Minchiate and in the Budapest/Met woodblock sheets, so probably not before the second half of the 15th century, perhaps via Aragonese influence (from normal suits in Aragon, where the "Portuguese" type is documented). Or vice versa. And where the Aroonese would have gotten it is another story.

Of course the Cary-Yale had a full complement of female courts in all four suits; this is almost as many as Frater Johannes has in the deck of 1377. Here I ask, which cities in Italy had the closest connection with Germany in the first half of the 15th century? Milan, Mantua, and Modena (and hence Ferrara) had court connections. Many cities, including Florence, in the first half of the century, made a point of distancing themselves from Germany, due to the old Guelph fear of the Emperors. There were, to be sure, connections via the printing of cards, both in Germany and by Germans moved south. But they normally printed whatever the local market wanted.

For this new experiment, whether in Milan or elsewhere, of adding a fifth suit, it seems reasinable, they also experimented with the German innovation of female courts, not only the Queen, but, in Milan at least, other courts. Such experimentation, however, requires an openness to German practices.

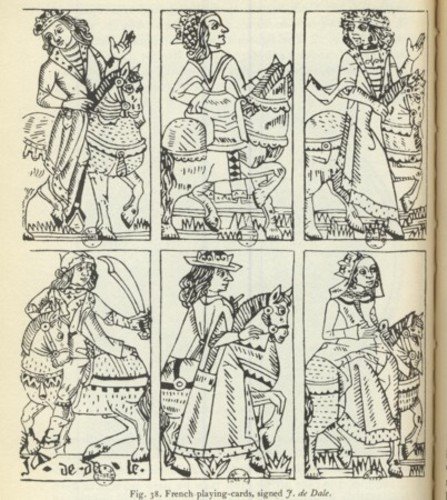

Along these same lines, there is a fact Dummett misses (he doesn't miss much!). This is that some French suits seem to have had female Knights as well as Queens (and hence perhaps also Pages). These are shown in vol. 1 of Arthur Hind's Introduction to a History of the Woodcut, where the females' suit-signs are conspicuous by their absence (as Ross once pointed out). They would have been added by stencil, just like on the numeral cards: