You've oversimplified my concept of the possible "evolution" of the deck, When someone copies a precious manuscript of a work he's never seen before, he doesn't compare it to all other available versions of the same text. He just copies, with errors, the one he's lucky enough to get. Someone else might have copied the same manuscript, with a different set of errors. But if the one copied from were lost, scholars wouldn't say that the later copy was copied from the earlier one, just because of the numerous commonalities between them.First I'll have to disabuse you of the notion that all these near-complete trionfi decks were circulating, and somehow ended up coalescing, remarkably containing all the subjects of the near-complete decks, as if the inventor toured Italy, collecting this deck of 14 here, this deck of 16 there, this deck of 20 here, and then mixed it all together into a super-Tarot, and then re-flooded Italy with various different orderings of this synthetic set of trumps. That seems to be the tough part, despite all the hoops and invented scenarios necessary to come up with to account for this "late standard" trump series.

The simple and only necessary answer - lost cards. All decks with any standard trumps are incomplete, in both suit and trump sequences. There is no need, and certainly no benefit, to posit multiple unknown chains of evolution. The analogy with the missing exemplar(s) that you cite for textual transmission is, in Tarot history, the 22-standard itself. The decks are missing pieces of this standard, that's all.

Similarly, if two works of art a few years apart seem to be different elaborations of the same core design, art historians don't just say that the one later in time is a variation on the first, but rather that each might be a variation on a simpler work of art now lost.

Likewise, when someone is designing a deck based on a previous deck, he doesn't compare it with other decks. He modifies what he has in front of him in accordance with his own ideas. He changes the order, changes the concept of a card, adds one or more, etc. I am imagining different 14-trump decks expanding to 16 in Milan, but that expansion not being popular. Someone else tries a 20 trump deck. Someone else later modifies that into a 22 trump deck. These latter two are all in one line of transmission. There can be many such lines, radiating out from various points, but downward only, meaning later in time.

If a text based on one manuscript gets popular, people want to see other versions of that text. They even travel great distnces to get them, such as Switzerland, France, or Greece. If such are available, at that point manuscripts are produced that reflect a variety of manuscript traditions.

So there are two different types of manuscript transmission, from a single manuscript when a text is not popular--let us call it type 1--and from many manuscripts when a text is seen as important and others can be obtained--call it type 2.

However the analogy with manuscripts breaks down here (although not with artworks). With manuscripts, the assumption is that there was an original one that can be reconstructed by comparing all the various copies and eliminating each one's errors. But with games, and inventions generally, that is not usually the case. Person A can copy person B's innovations by incorporating them within person A's existing pattern so as to make something that is not a closer approximation of anything that pre-existed both. For example, if inventor A has an automobile that looks and works great except for a ridiculously fuel-inefficient, large, and malfunction-prone engine, he can incorporate inventor B's marvelous engine and no one will think he has reconstructed something that existed in the past but was lost.

So we might have the situation that one particular type 1 modification of the original deck becomes in demand: in 1452 or so if Milan, perhaps earlier if elsewhere. That is one that expands the 14 to either 20 or 22. The basis for thinking that such might have happened is that certain cards not present in the Cary-Yale (assuming that 2 virtues, Time, and Fortune are missing) are invariably in the same relative place in the order in both the A and C orders (Popess, Pope, Hanged Man, Devil, Arrow, Star, Moon, Sun). That this is the case is accounted for by its being a type 2 transmission (like putting B's engine into A's car). I say "20 or 22" because the Devil and Arrow are not present in any of the PMB-type decks. O'Neill calculated the odds of that happening by chance. The math suggests, although not definitively, that it is not by chance. To be sure, it could have been by choice.

Then, once there are 22 trumps, further regional changes occur, of type 1, giving us the three main types and many differences within them, also type 1. These Dummett has accounted for. There are also a few more type 2 changes (i.e. influences from another region), most notably in Piedmont and Sicily. (The governor of Sicily who introduced the game was most familiar with Roman Minchiate, but spent the 2 previous years as governor of Lombardy.)

The question then arises, are 14, 16, 20, and 25 viable trump numbers for a trick-taking game with five suits? I include 25 because that is one theory about the number of cards in the Cary-Yale.

That is where the rest of what you said in your post is relevant. You say:

Something is wrong. There is the Regle of 1637, which says that there should be three players at most, and that when two play, there is a "dead" hand. Yet there are 22 trumps here, the same as in Bologna.With these principles accepted, you can see that the game does not work symmetrically for any other number of players. 3 or less gives too many cards to each player, while 5 or more too few.

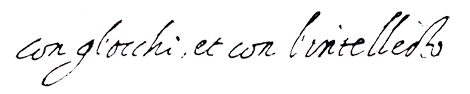

There is also Galeazzo Maria's letter home from Ferrara in 1457, where he says he played "cards and tennis" with his host Francesco Pico della Mirandola (Lubkin, p. 309, http://books.google.com/books?id=NUoR2W ... en&f=false). No mention of others playing with him, and Lubkin (p. 92, http://books.google.com/books?id=NUoR2W ... ot&f=false) gives this note as a comment on his life-long passion for tarot,Mais auant que d'entrer plus auant dans le destail de ce jeu, il me semble a propos de dire qu'il n'y faut estre que trois personnes au plus, & qu'il n'est pas fort agreable a deux, estant mesme encore necessaire d'y en supposer vn troisiesme que l'on appelle le Mort, duquel l'on tire selon le hazard autant de cartes que les autres font de mains pour estre emportées par celuy qui est le plus fort. Neantmoins ceux qui l'ayment extresmement s'y peuuent quelquefois diuertir de la sorte.

(But before going further into the details of this game, it seems appropriate to say that there should be three people at most, and it is not agreeable for two, it being then necessary to assume a third called the Dead, which is dealt by chance as many cards as the other hands, to be taken by the person who is the strongest. However those who love it extremely can sometimes be entertained so.)

Your argument for four persons and 22 trumps also assumes the designer thought in terms of the "best case" and "worst case" scenarios. I didn't follow all of your argument, because you talk of the possibility of being dealt all the "counting cards"--19 or 20--and then you switch to the possibility of being dealt all the trumps, i.e. 21. Which is it they have to have, 19, 20, or 21 cards? I will assume the latter, since it seems most desirable to win all the tricks, and that is what you have the dealer getting.

In the Regle, there in fact does seem to be an effort to give every player (of 3) at least 21 cards. It suggests shortening the deck. Immediately after my previous quote, it says:

I'm not sure if this is meant as a requirement of the game or not, but a practice of removing 12 cards, for 3 players, is consistent with your point; now, instead of just the dealer, every player has the possibility, however remote, of getting all the trumps.Mais afin de le trouuer plus agreable il est bon d'oster douze cartes inutiles des quatre peintures, c'est a dire trois de chacunes, sçauoir les dix, neuf, & huict des couppes & deniers, & les trois, deux & az d'espées & bastons qui sont les moindres de chacun de ces points, par ce que les hautes de couppes & deniers ne sont pas de plus grande valeur que les basses des Espées & bastons.

(But in order to find it more pleasant, it is good to remove twelve unnecessary cards of the four colors, i.e. three each, i.e. ten, nine, eight cups and coins, and three, two and ace swords and batons, which are the smallest of each of these colors, for the high ones of cups and coins are not more valuable than the low of swords and batons.)

But I don't see why it had to be part of the original design, as opposed to something thought of later (since the probability is so low). Also, without knowing how many cards were used in a tarot deck in Ferrara 1456 (70 or 78) with four players, we don't know how many cards each player got then. If it was a 70 card deck, as suggested by the Ferrara note of 1457, each person would get 17 except the dealer with 19. You can't be sure of getting all the tricks with that, unless there are only 20 trumps, including the Fool.

While the idea of getting 21 cards in a game with 21 trumps is a nice symmetry, and one indeed held onto, I don't see why it should have been part of the game from the beginning--it is not part of your seven principles--and it is especially troublesome in 1456 Ferrara, given the 70 card tarot pack note of 1457.

The lack of a "verzicole" rule in Bologna would have definitely been suggestive of some sort of priority, I'm not sure what. But it was there. And the symmetry with 21, kept even in 1637, is indeed interesting, assuming a 78 card pack with 4 players and 66 with three. I just don't know what can justifiably be made of it, regarding the "original designer". So for the present I'm back to not being able to give priority to anywhere, or to say that there were more than 20 trumps in 1456.