Compare the Charles VI lines with the Rothschild cards' (particularly hands and faces). I think appeals to generic style is a blunt way to date objects; it might only work within less than a couple of decades at best, unless you already have the artist pegged. Do you want to push Charles VI back to the 1420s or 30s just because it isn't an example of the latest style in Florentine taste in art?

More likely, cards are quick and cartoon like; they don't really reflect the dominant, let alone the avant garde, style in art. Bembo's are exceptional, in being specific commissions in a tradtional style for a specific patron; Charles VI and Rothschild may be high-end retail objects, dedicated to no particular person. And even if they were, how do we know that they wanted the "new" style? Playing cards generally don't break ground in art.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

12I think,

I agree with Ross in these points.

Is it so sure, that the cards were made in Florence?

I think, I have read, that the cards were printed and then painted (don't ask me, where). Shouldn't one assume, that this technology would be rather early in 1423?

The 1423 cards, if the number "8 cards" is correct and not has to be interpreted as "8 decks", were very expensive. Nearly one ducat for each card. I would expect a little bit more than the Rothschild cards.

Generally I think, that it's the more promising research strategy to follow the already known playing card artists, instead investigating "similarities".

In the case of Lo Schegia we at least know, that the man once made playing cards. Also we know (only interesting, if we assume, that it is Medici related) that Scheggia already had worked for the Medici.

There are some early names of playing cards known, but naturally less as in later times. The Jacobsen list had some, 2 worked for the Lapini and in the early Arezzo articles appear producer names, as far I remember.

Naturally it's not impossible, that Giovanni dal Ponte was active in the maner, as you described.

Here's his catasto file for Giovanni di Marco ...

http://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/c ... D+50002985

... and this is a map, where one can identify the locations. In GdM's case it's "21 = Carro"

http://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/c ... 0_map.html

I agree with Ross in these points.

Is it so sure, that the cards were made in Florence?

I think, I have read, that the cards were printed and then painted (don't ask me, where). Shouldn't one assume, that this technology would be rather early in 1423?

The 1423 cards, if the number "8 cards" is correct and not has to be interpreted as "8 decks", were very expensive. Nearly one ducat for each card. I would expect a little bit more than the Rothschild cards.

Generally I think, that it's the more promising research strategy to follow the already known playing card artists, instead investigating "similarities".

In the case of Lo Schegia we at least know, that the man once made playing cards. Also we know (only interesting, if we assume, that it is Medici related) that Scheggia already had worked for the Medici.

There are some early names of playing cards known, but naturally less as in later times. The Jacobsen list had some, 2 worked for the Lapini and in the early Arezzo articles appear producer names, as far I remember.

Naturally it's not impossible, that Giovanni dal Ponte was active in the maner, as you described.

Here's his catasto file for Giovanni di Marco ...

http://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/c ... D+50002985

... and this is a map, where one can identify the locations. In GdM's case it's "21 = Carro"

http://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/c ... 0_map.html

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

13I will address Ross's argument in a later post. It's my issue 5. I'd do it now, except that for clarity I need to put the Rothschild and Charles VI Emperor's side by side, and I have to get a friend with better software to do that for me.

I would like very much to know if the Rothschild cards were printed first and then painted. That would say something. I am not wedded to 1423. Any time before 1434 will work, but other things being equal, earlier rather than later. I do not expect to have proof; I am only looking at pros and cons, and my suspicion is that there are more pros than cons. There is, to be sure, a conservatism in card-making, a tendency to stick closely to what came before. But when is that "before"? I propose that it's when the style was in fashion. I'll say more later, when I have the two Emperors side by side.

Before going on to the fifth issue that I stated at the beginning of the thread, I want to address an issue that I was not aware of then, namely, that of the influence of Spanish-suited cards on the Rothschild. This issue was discussed on the ATF thread but I want to add some things. The most thorough starting point is on Andy's Playing Cards, the "Ferrara" page (http://l-pollett.tripod.com/cards89.htm).

First, the Rothschild has a bearded Page of Coins, a rather unusual feature in Italian pages, which are typically presented as young and beardless:

Andy says of this feature:

There is also, in the Rothschild, the double-shell tortoise shield of the Knight of Swords. It has more significance than just protection. Andy says:

Ross, at http://www.tarotforum.net/showpost.php? ... stcount=69, says, based on this resemblance, that the Knight of Swords is a defeated Saracen. Andy's page on the Italy 2 tends to support that:

'

'

On the ATF thread, it is proposed that Florentines would have become familiar with this deck when Alfonso, King of Aragon, became King of Naples. But this didn't happen until 1442 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfonso_V_of_Aragon). Before that the ruler was Rene of Anjou).

Here Fiorini has a relevant observation, addressing the feature of the double shield:

I would like very much to know if the Rothschild cards were printed first and then painted. That would say something. I am not wedded to 1423. Any time before 1434 will work, but other things being equal, earlier rather than later. I do not expect to have proof; I am only looking at pros and cons, and my suspicion is that there are more pros than cons. There is, to be sure, a conservatism in card-making, a tendency to stick closely to what came before. But when is that "before"? I propose that it's when the style was in fashion. I'll say more later, when I have the two Emperors side by side.

Before going on to the fifth issue that I stated at the beginning of the thread, I want to address an issue that I was not aware of then, namely, that of the influence of Spanish-suited cards on the Rothschild. This issue was discussed on the ATF thread but I want to add some things. The most thorough starting point is on Andy's Playing Cards, the "Ferrara" page (http://l-pollett.tripod.com/cards89.htm).

First, the Rothschild has a bearded Page of Coins, a rather unusual feature in Italian pages, which are typically presented as young and beardless:

Andy says of this feature:

On Andy's "Italy 2" page (http://l-pollett.tripod.com/cards77.htm), it is the Page of Batons that wears the beard. Beards are also on the Knight and King of Swords....this is not a unique feature: in fact, a similar one is found in the so-called Italy 2 cards (after their catalogue number in the Fournier Museum of Alava, Spain), an archaic Latin-suited pattern of Moorish inspiration, surely earlier than the RS by several decades, which testifies the existence of bearded knaves at an early stage of Western playing card history.

There is also, in the Rothschild, the double-shell tortoise shield of the Knight of Swords. It has more significance than just protection. Andy says:

Here it is:This particular shape, and the position it is held in, are both very similar to the shield carried by the Moorish cavalier of Swords in the aforesaid Italy 2 deck.

Ross, at http://www.tarotforum.net/showpost.php? ... stcount=69, says, based on this resemblance, that the Knight of Swords is a defeated Saracen. Andy's page on the Italy 2 tends to support that:

But now there is a potential problem for Fiorini's proposal that the cards were done in the 1420s. Andy has a map showing the early spread of the "Italy 2" deck: it includes Milan and Venice but not Florence (although admittedly, Florence is just on the other side of the Appenines).The cavalier of Swords is also a Moor; note the pointed cap and the shield, both in the fashion of the Saracens, although the blade of the sword is not curved.

On the ATF thread, it is proposed that Florentines would have become familiar with this deck when Alfonso, King of Aragon, became King of Naples. But this didn't happen until 1442 (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfonso_V_of_Aragon). Before that the ruler was Rene of Anjou).

Here Fiorini has a relevant observation, addressing the feature of the double shield:

Ross posted the Starnina painting, in black and white, at the beginning of http://www.tarotforum.net/showpost.php? ... stcount=69. It is certainly possible that a painter in Florence might have acquired a deck of Spanish-suited cards in the 1420s; on Andy's map, it looks like the cards made it as far as Bologna and Ferrara, which certainly traded with Florence. But it is more likely in the case of one who had close contact with a painter who had actually been where this deck had been used and knew something of what the double shield signified (i.e. Moors).Facilmente documentabile in dipinti di matrice spagnola, non lo è altrettanto nell'arte italiana: l'unico esempio che sono riuscita a reperire è rappresentato dalla Battaglia tra Orientali conservata nel Museo di Altenburg ed eseguita da Gherardo Stamina. Notizia di scarso interesse se npn fosse che l'artista in questione, attivo a Firenze dopo un lungo soggiorno a Valencia, fu il principale maestro di Giovanni di Marco, il quale potrebbe essersi ispirato allo Stamina per l'inserimento di questo colto riferimento.

(Easily documented in paintings of the Spanish matrix, it is not so in Italian art: the only example I could find is represented by the Battle among Orientals preserved in the Museum of Altenburg done by Gherardo Starnina. The artist in question made news of little interest; active in Florence after a long stay in Valencia, he was the main master of Giovanni di Marco, who may have been inspired by Starnina for the inclusion of this cultural reference.)

Last edited by mikeh on 15 Feb 2014, 22:23, edited 3 times in total.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

14We've Alfonso in Italy and fighting at least in 1423 (just that Imperatori date, the triumphal festivity with Johanna), which was followed by Johanna's resistance short time later.

I think, Alfonso was back in Italy before 1442 (at least he was prisoner of Filippo Maria Visconti already in late 1435, following a battle at sea), short after Johanna's death.

Likely one can get the dates better, easily.

The knight with the Moorish shield looks, as if he has lost ... perhaps this plays a role.

Added:

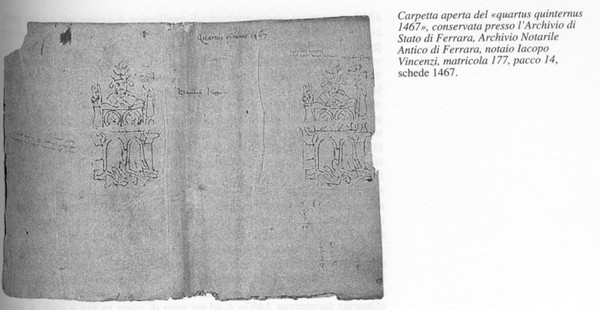

Here's, what Gerardo Ortalli says at page 194 and 197 in The Prince and the Playing Cards in Ludica 1996: According this, the Rothschild cards are pre-printed.

http://www.viella.it/rivista/460

p. 194

p. 197

Added:

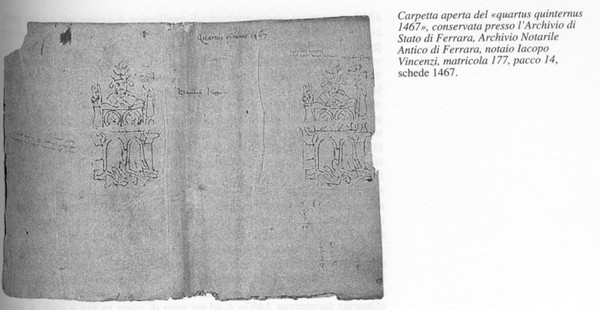

Before somebody asks, what the Vincenzi Tarot is ... that's it, reported by Adriano Franceschini in the same Ludica edition.

.... :-) ... seems to express. "Huhu, here I am ..." ... :-)

I think, Alfonso was back in Italy before 1442 (at least he was prisoner of Filippo Maria Visconti already in late 1435, following a battle at sea), short after Johanna's death.

Likely one can get the dates better, easily.

The knight with the Moorish shield looks, as if he has lost ... perhaps this plays a role.

You can do that, by opening the browser twice and giving each part a reduced window.I have to get a friend with better software to do that for me.

.... I'll say more later, when I have the two Emperors side by side.

Added:

Here's, what Gerardo Ortalli says at page 194 and 197 in The Prince and the Playing Cards in Ludica 1996: According this, the Rothschild cards are pre-printed.

http://www.viella.it/rivista/460

p. 194

p. 197

Added:

Before somebody asks, what the Vincenzi Tarot is ... that's it, reported by Adriano Franceschini in the same Ludica edition.

.... :-) ... seems to express. "Huhu, here I am ..." ... :-)

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

15Ross wrote

The Rothschild on our left is Late Gothic, theCharles VI on the right firmly Renaissance. On the left, the figure of the Emperor is generally flat, except for the folds in the tunic, for which da Ponte and other Late Gothic artists knew how to create depth by means of shading. The arm reaching for the scepter is especially awkward, as well as its connection to the hand grasping it. In contrast, the one on the right has volume, due to knowledge of perspective, and the arm is more natural, with the hand clearly part of the arm. On the left we see the usual fine details we expect in Late Gothic fabric depiction. On the right, there is less attention to the fabric. Fancy clothing was out of fashion by its time. What remains is homage to past Emperor cards and to emperor's exalted status. The two little figures below the right-hand Emperor are done without any sense of being physically part of the scene. That is a medieval strategy. On the right, the two figures have been changed to boys, so that physically the whole scene is believable. (I am not sure how they manage to kneel on air, but I am not saying the artist was perfect.) Also the way the two boys line up shows a knowledge of single-point perspective with a vanishing point inside the frame. That is lacking on the left. Also, the head of the boy in back is slightly smaller than that of the one in front, also creating an illusion of depth. The platform also has depth, lacking on the left. The net result is a Renaissance image on the right, a late-medieval image on the left. The change was sudden, starting with Masaccio and Brunelleschi in Florence, and probably a similar trend in Bruges, although it isn't documented until around 1433 with van Eyck. Some people (e.g. Hockney) speculate that it had to do with the development of large lenses for focusing images that could be traced (which is not to say that these marvelous paintings are just tracings; it is more that they show a new way of seeing.)

Yes, some people might have preferred the old style. But there is no indication that such was true of the most influential families in Florence. The new style was seen as magical, almost miraculous, like having the person in front of one, writers said. An artist who had mastered it would not want it to appear that he hadn't. Although there is an inherent conservatism in card designs, the Charles VI Emperor shows what could be done. Even while in the new style, it was late enough so that it is not at all ground-breaking. Some artists did have trouble with the new style. That may be why the Catania looks more medieval than the Charles VI (flat, less realistic)--or, although done in Florence, was for a family outside of Florence (i.e. Sforza) who wanted its cards more Gothic, as in Milan. But even the Catania, unlike the Rothschild, shows knowledge of the principle of one-point perspective (the Chariot). Nothing is definite, to be sure, as we don't know the particular circumstances for any of these decks. We can only judge by what is known in relation to other things known.

Thanks for the text about how the Rothschild was a painted woodcut, Huck. That may explain the squiggly lines in the beards, if they were in the woodcut but painted over in white. It might also explain the cartoonish quality of many of the cards that Ross noted., My impression is that that was a common method of producing cards in the 1420s in Italy. It wouldn't have had to wait until even 1430.

I certainly don't want to push the Charles VI back! Probably the best comparison will be with the Emperor cards, since the subjects are the same ( higher res at http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-CNly6whjDyE/U ... hVIEmp.jpg).Compare the Charles VI lines with the Rothschild cards' (particularly hands and faces). I think appeals to generic style is a blunt way to date objects; it might only work within less than a couple of decades at best, unless you already have the artist pegged. Do you want to push Charles VI back to the 1420s or 30s just because it isn't an example of the latest style in Florentine taste in art?

More likely, cards are quick and cartoon like; they don't really reflect the dominant, let alone the avant garde, style in art. Bembo's are exceptional, in being specific commissions in a tradtional style for a specific patron; Charles VI and Rothschild may be high-end retail objects, dedicated to no particular person. And even if they were, how do we know that they wanted the "new" style? Playing cards generally don't break ground in art.

The Rothschild on our left is Late Gothic, theCharles VI on the right firmly Renaissance. On the left, the figure of the Emperor is generally flat, except for the folds in the tunic, for which da Ponte and other Late Gothic artists knew how to create depth by means of shading. The arm reaching for the scepter is especially awkward, as well as its connection to the hand grasping it. In contrast, the one on the right has volume, due to knowledge of perspective, and the arm is more natural, with the hand clearly part of the arm. On the left we see the usual fine details we expect in Late Gothic fabric depiction. On the right, there is less attention to the fabric. Fancy clothing was out of fashion by its time. What remains is homage to past Emperor cards and to emperor's exalted status. The two little figures below the right-hand Emperor are done without any sense of being physically part of the scene. That is a medieval strategy. On the right, the two figures have been changed to boys, so that physically the whole scene is believable. (I am not sure how they manage to kneel on air, but I am not saying the artist was perfect.) Also the way the two boys line up shows a knowledge of single-point perspective with a vanishing point inside the frame. That is lacking on the left. Also, the head of the boy in back is slightly smaller than that of the one in front, also creating an illusion of depth. The platform also has depth, lacking on the left. The net result is a Renaissance image on the right, a late-medieval image on the left. The change was sudden, starting with Masaccio and Brunelleschi in Florence, and probably a similar trend in Bruges, although it isn't documented until around 1433 with van Eyck. Some people (e.g. Hockney) speculate that it had to do with the development of large lenses for focusing images that could be traced (which is not to say that these marvelous paintings are just tracings; it is more that they show a new way of seeing.)

Yes, some people might have preferred the old style. But there is no indication that such was true of the most influential families in Florence. The new style was seen as magical, almost miraculous, like having the person in front of one, writers said. An artist who had mastered it would not want it to appear that he hadn't. Although there is an inherent conservatism in card designs, the Charles VI Emperor shows what could be done. Even while in the new style, it was late enough so that it is not at all ground-breaking. Some artists did have trouble with the new style. That may be why the Catania looks more medieval than the Charles VI (flat, less realistic)--or, although done in Florence, was for a family outside of Florence (i.e. Sforza) who wanted its cards more Gothic, as in Milan. But even the Catania, unlike the Rothschild, shows knowledge of the principle of one-point perspective (the Chariot). Nothing is definite, to be sure, as we don't know the particular circumstances for any of these decks. We can only judge by what is known in relation to other things known.

Thanks for the text about how the Rothschild was a painted woodcut, Huck. That may explain the squiggly lines in the beards, if they were in the woodcut but painted over in white. It might also explain the cartoonish quality of many of the cards that Ross noted., My impression is that that was a common method of producing cards in the 1420s in Italy. It wouldn't have had to wait until even 1430.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

16This looks to me not probable, that it was already "common" in the 1420s. There's something like a "first known" in 1422 and some time there surely must have been, before it can be called "common". Perhaps "around 1440" it'smikeh wrote: Thanks for the text about how the Rothschild was a painted woodcut, Huck. That may explain the squiggly lines in the beards, if they were in the woodcut but painted over in white. It might also explain the cartoonish quality of many of the cards that Ross noted., My impression is that that was a common method of producing cards in the 1420s in Italy. It wouldn't have had to wait until even 1430.

common. And then still it's a question of the location.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

17Huck wrote, about my "impression" that woodblock cards were "common" in the 1420s"

Fortunately, for the Rothschild to have been woodcuts before being painted, I don't need to say that woodcut-produced cards were common in 1420s Florence. The Rothschild is not a common deck, so all I need is that it probably wasn't unheard of there, by the early 1430s (before 1434).

To be sure, the first extant dated woodcut is a Madonna of 1418 Flanders (according to Hind, An introduction to the history of woodcut, 1935, p. 96), followed by a St. Christopher of 1423 Augsburg. But these are sacred images, worthy of being preserved; cards weren't. Given the popularity of cards, and the conservatism of monks, I would guess that cards were earlier. About playing cards from woodcuts, Hind says (p. 84):

Hind goes on to note, of course, St. Bernardino's diatribe in 1424 to persuade the players to burn their cards. We have no way of knowing, to be sure, how common these cards were at the time.

One way in which prints on paper from woodblocks might have been produced early on is from the woodblocks used for making textile prints. We know about them from the numerous Late Gothic depictions of sumptuously decorated clothing, including that depicted in the painted part of the Rothschild cards. Hind observes that textile printing was common throughout the middle ages, although not with pictured figures until the second half of the 14th century (p. 67). He gives numerous examples on textiles from about 1400. He adds (p. 69):

He gives several examples; the only problem is that there is no extant corresponding textile, so this use is only "probable". I would imagine that such a "probable" use would apply in Florence, which it is my impression was even in the early 15th century a center of textile production.

Ah, yes. You've caught me on that before. I keep assuming that with all those playing card prohibitions before 1420 (including in Italy), that there was some means of mass-producing cards, given the labor shortage after the Black Death, and that southern Germany or Flanders wouldn't have been the only place such techniques were used. But indeed I have no proof for Florence.This looks to me not probable, that it was already "common" in the 1420s. There's something like a "first known" in 1422 and some time there surely must have been, before it can be called "common". Perhaps "around 1440" it's

common. And then still it's a question of the location.

Fortunately, for the Rothschild to have been woodcuts before being painted, I don't need to say that woodcut-produced cards were common in 1420s Florence. The Rothschild is not a common deck, so all I need is that it probably wasn't unheard of there, by the early 1430s (before 1434).

To be sure, the first extant dated woodcut is a Madonna of 1418 Flanders (according to Hind, An introduction to the history of woodcut, 1935, p. 96), followed by a St. Christopher of 1423 Augsburg. But these are sacred images, worthy of being preserved; cards weren't. Given the popularity of cards, and the conservatism of monks, I would guess that cards were earlier. About playing cards from woodcuts, Hind says (p. 84):

Hind adds (p. 84) thatIn the first place the production of playing-cards must have been a thriving industry, especially at Ulm 2, at the end of the XIV and beginning of the XV century. In spite of the fact that no existing pack of cards can be dated with any certainly before about 1450, this does not rule out the probability of woodcuts having been used by about 1400, if not earlier, in their production.

________________

2. See Felix Fabri, Tractatus de Civitate Ulmensi, herausgegeben von G. Veesenmeyer, Litterarisches Verein in Stuttgart 1889, pp. 145, 146.

Prints on paper can also be dated by their style. Hind observes (p. 79):Through the very nature of their use cards are the most unlikely things to be preserved.

On woodcut-produced cards in Italy, there is also documentation. Here is Hind p. 80:It seems unlikely that any large supplies of paper were available before the latter part of the XIV century 2, and this was probably an important factor in determining the period at which the printing of pictures was introduced. Judged from the style of their design, the woodcuts which appear to the be the earliest printed on paper should be dated about 1400, hardly later, and hardly more than ten or twenty years earlier.

Kristeller notes a certain Federico de Germania who sold cartas figuratas et pictas ad imagines et figures sanctorum at Bologna in 1395, and a card-maker (pittor di naibi) of Florence, Antonio di Giovanni di Ser Francesco, who declares among his property in 1430 'wood blocks for playing-cards and saints'. 3.

_______________________

Kupferstich und Holzschnitt, 1922, pp. 20 and 21. There is no proof that Federico de Germania printed his cards from blocks, but as the document in which he is mentioned is an action against him for coining false money, Kristeller thinks it highly probable that a die-cutter would have been equally conversant with block-cutting. It is worth noting in this relation a fact emphasized by Bouchot (Ancetre de la gravure su bois/i], p. 22) that in France early woodcuts seem to have sometimes been regarded as [malfacons (contraband), a sort of false coin in the eyes of the build of Imagiers.

Hind goes on to note, of course, St. Bernardino's diatribe in 1424 to persuade the players to burn their cards. We have no way of knowing, to be sure, how common these cards were at the time.

One way in which prints on paper from woodblocks might have been produced early on is from the woodblocks used for making textile prints. We know about them from the numerous Late Gothic depictions of sumptuously decorated clothing, including that depicted in the painted part of the Rothschild cards. Hind observes that textile printing was common throughout the middle ages, although not with pictured figures until the second half of the 14th century (p. 67). He gives numerous examples on textiles from about 1400. He adds (p. 69):

The printers of textiles may also have sometimes pulled impressions on paper as patterns, and some of the earliest prints on paper (known for the most part only in single impressions) may have been made for this purpose.

He gives several examples; the only problem is that there is no extant corresponding textile, so this use is only "probable". I would imagine that such a "probable" use would apply in Florence, which it is my impression was even in the early 15th century a center of textile production.

Last edited by mikeh on 02 Apr 2014, 23:30, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

18I remember, that they are some older textile prints ... but can't display a link to them.

Also there were modern news to playing cards in Spain, which claimed printed playing cards around 1400 (from my perspective also lost in the web).

But Spain isn't Italy, and it might well be, that technology export went rather slow in this time. Once the persons, who had the "mystery how to do it", might have kept it for themselves to dominate the market, and actually all traffic was hindered by the repeating plagues. The playing card press, which arrived in Ferrara 1437, was still considered a novelty, though we have this man with wood blocks already in Florence already in 1430.

In Franco's lists around the time after the begin of the 1440s we see used the rather seldom expression "FOR", which Franco explains with "di forma, made with woodblocks;" ... possibly an indication, that it was still rare then. But, after only a short time with some "FOR" the expression disappears from the lists, possibly indicating, that the use of "forma" had become very common in quick time. Then we have something like a break down of the market (around 1445), possibly indicating, that the new heavy use of playing cards after a technology innovation caused a prohibition phase for some time, which was overcome with the developments in 1447.

This is naturally only speculation on the few numbers, that we get from the silk dealer list.

On the other hand we have the development of block books (an advanced woodblock technology) already before 1450, however, this form of book printing became only used in Germany and the Flemish countries.

Also there were modern news to playing cards in Spain, which claimed printed playing cards around 1400 (from my perspective also lost in the web).

But Spain isn't Italy, and it might well be, that technology export went rather slow in this time. Once the persons, who had the "mystery how to do it", might have kept it for themselves to dominate the market, and actually all traffic was hindered by the repeating plagues. The playing card press, which arrived in Ferrara 1437, was still considered a novelty, though we have this man with wood blocks already in Florence already in 1430.

In Franco's lists around the time after the begin of the 1440s we see used the rather seldom expression "FOR", which Franco explains with "di forma, made with woodblocks;" ... possibly an indication, that it was still rare then. But, after only a short time with some "FOR" the expression disappears from the lists, possibly indicating, that the use of "forma" had become very common in quick time. Then we have something like a break down of the market (around 1445), possibly indicating, that the new heavy use of playing cards after a technology innovation caused a prohibition phase for some time, which was overcome with the developments in 1447.

This is naturally only speculation on the few numbers, that we get from the silk dealer list.

On the other hand we have the development of block books (an advanced woodblock technology) already before 1450, however, this form of book printing became only used in Germany and the Flemish countries.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

19I finally got from Interlibrary Loan a copy of Luciano Bellosi's 1985 article attributing the Rothschild cards to da Ponte, reprinted in his book of 2000, the relevant section on pp. 200-201. He provides us with comparisons to del Ponte's works that have not been made so far on this thread. Here are the pictures in the article, followed by what he says about them, in my English translation (the Italian original is at the end of this post).

Not pictured are the St. Julian and St. John the Baptist in the Museo Horne, the St. Francis in Oakly [Oakley?] Park, the St. George triptych in Columbia, and the Saint Peter enthroned of San Piero Scheraggio. Other than the St. George, I can't find them on the Web, or I'd display them.

In what follows, the numbers in parentheses are to these pictures, which Bellosi has in the margin next to the sentences where I put them. The one number in brackets is where a new page starts.

I think his points of comparison to del Ponte.are well taken, although I don't quite understand, at the end, what is "di sciatto e di spiegazzato" (slopply and crumpled) about the drawing of #266; it looks pretty good to me.

The designation of one of the cards as "Mondo" (World) is of course what leads him to say they are tarocchi. But if so it is not like any "World" card, except in showing someone holding a circular object. I would think it might be an early Page of Coins. Perhaps these standing figures weren't originally defined clearly as pages, and hence young as opposed to just servants. The d'Este page of staves is not young, for example.

Not pictured are the St. Julian and St. John the Baptist in the Museo Horne, the St. Francis in Oakly [Oakley?] Park, the St. George triptych in Columbia, and the Saint Peter enthroned of San Piero Scheraggio. Other than the St. George, I can't find them on the Web, or I'd display them.

In what follows, the numbers in parentheses are to these pictures, which Bellosi has in the margin next to the sentences where I put them. The one number in brackets is where a new page starts.

I think his points of comparison to del Ponte.are well taken, although I don't quite understand, at the end, what is "di sciatto e di spiegazzato" (slopply and crumpled) about the drawing of #266; it looks pretty good to me.

The designation of one of the cards as "Mondo" (World) is of course what leads him to say they are tarocchi. But if so it is not like any "World" card, except in showing someone holding a circular object. I would think it might be an early Page of Coins. Perhaps these standing figures weren't originally defined clearly as pages, and hence young as opposed to just servants. The d'Este page of staves is not young, for example.

Here is the Italian:A drawing by Giovanni del Ponte and some tarot cards

Nos. 563 of the Corpus of Degenhart refers to a sheet of unknown location, but until 1940 in Rotterdam (266). There you will see two young men, turned toward the right with a certain ostentation. In whole figure, a bit grim of expression and sketched with remarkable rapidity and ease, they seem distant from both the clean lines and the whiteness of the human forms of Pesellino and those more abruptly squared of Apollonio di Giovanni, two reference points indicated by Degenhart and Schmitt for these male characters. Slender and elegant, they still participate in a Gothic "verticality " and seem closely related to the cursive style of Giovanni del Ponte, a painter of at least a generation earlier than the other two, who trained in the artistic ambit of Florence in the first two decades of the fifteenth century, in proximity to Lorenzo Monaco and, above all, to Starnina, alias "Master of the lively Child" 52.

The cursive character of this design is particularly comparable with certain works of Giovanni, for the speed of execution, almost resembling the sketches - for example - of the two doors of the tabernacle with St. Julian and St. John the Baptist in the Museo Horne. By Giovanni del Ponte there exist, however, artisan products executed in an almost identical technique with an even greater cursive treatment (267, 269, 271). I am referring to a deck of tarocchi of which have come down to us only a few pieces, preserved in the Rothschild collection in the Cabinet of Drawings at the Louvre. They are considered things of northern Italy at the end of the fifteenth century 53, but their real environment, and even their author, are testimony enough to a relationship with the paintings of Giovanni del Ponte.

The Emperor compares well with Saint Anthony Abbot on a predella in the Musées Royaux Brussels or with the St. John the Baptist ex-Horne; the Knight of Staves with St. Francis of the altarpiece in the collection of the Earl of Plymouth, Oakly Park (269-270, 267); the World (?) with [201] some old men who appear in the predella of the panel Stories of St. Catherine of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Budapest (271-272) (especially in the picturesque ripple of the woolly beard); the Knight of Staves with the St. George triptych of the Kress triptych at Columbia 54 and also with the two dandies in the drawing with which we started (266-267). If you consider the more "stained " effect, almost backlit on the gold bottom of the tarocchi card, which is colored; you will notice, in addition to the typological affinities, the stringent similarities in the signs of the outline, marked yet flexible and in the watercolors cursory and almost impressionistic. The design of the Knight of Staves of the Rothschild tarot is in perfect correspondence with other depictions by Giovanni del Ponte, such as the young king and the groom who assists the horses on the right of the Adoration of the Magi of the Brussels predella already cited (268). The curious way of holding the hands one on the other in the youth in the second plane of the drawing, as if handcuffed, is a unique formula of Giovanni del Ponte and he is found almost identically - for example - in the cardinal sitting to the left in the panel of Saint Peter enthroned, the predella of San Piero Scheraggio.

With Giovanni del Ponte is explained very well the hurried graphics of the repeated lengths of the fabrics and something sloppy and crumpled which makes the design of the two young men of unknown location a version a bit of a romantic and "bohemian" version of the up to date elegance in the mode of dress fashionable 1425-30 that you see in Masolino, Govanni Toscan,i etc.

______________________________

52 . For Giovanni di Marco, better known than Giovanni del Ponte, arriving in Florence from about 1405-10 to 1437, please see the details in F. GUIDI, Per una nuova cronologia di Giovanni di Marco (For a New Chronology of Giovanni di Marco), in "Paragone", 223, 1968, pp. 27-46; Idem. Ancora su Giovanni di Marco (Again onGiovanni di Marco), in "Paragone", 239, 1970, p. 11-23.

53. See the catalog edited by J. R. PIERRE , for the exhibition Les Incunables de la collection Edmond de Rothschild, Musée de Louvre, 1974, p. 27 and 28. The Rothschild tarocchi had been published by L. PUPPI , About Bonifacio Bembo and his workshop, in "Art Lombarda ", 1959, p. 245-252, who put them in relationship with Bembo, attributing them to "Master of the tarot of Castello Ursino." Puppi , p. 250, fig. 13, also published a knight of swords in the Civic Museum of Bassano , which is part of the same series of Rothschild tarocchi.

54. In this regard , it is interesting to quote the opinion of R. KLEIN (Les tarots enluminée emes du siècle, in "L'Oeil", January 1967, p. 52) that the "knights " of this series are represented as a St. George .

Un disegno di Giovanni del Ponte e alcune carte da tarocchi

Il. nn. 563 del Corpus del Degenhard si riferisce ad un foglio di ubicazione sconosciuta, ma che fino al 1940 si trovava a Rotterdam [266]. Vi si vedono due giovani, voltati verso destra con una certa ostentazione. A figure intera, un po' torvi nell'espressione e schizzati con notevole rapidità e disinvoltura, sembrano lontani sia dalla pulizia formale e dal candore del Pesellino che dalle forme umane più bruscamente squadrate di Apollonio di Giovanni sono i due punti di riferimento indicati dal Degenhart e dalla Schmitt per questi personaggi maschile. Slanciati ed eleganti, essi partecipano ancora del "verticalismo" gotico e mi sembrano strettamente affini ai modi corsivi di Giovanni del Ponte, un pittore più antico di almeno una generazione rispetto agli altri due, formatosi nell'ambiente artistico fiorentino dei primi due decenni del Quattrocento in prossimità di Lorenzo Monaco e, soprattutto, della Starnina, alias "Maestro del Bambino vispo" 52.

Il carattere corsivo di questo disegno è particolarmente ben confrontabile con certe opere di Giovanni che, per la rapidità dellàesecuzione, assomigliano quasi a degli abbozzi, come - ad essempio - i due sportelli di tabernacolo con San Giuliano e san Giovanni Battista già nel Museo Horne. Di Giovanni del Ponte esistono, comunque, dei prodotti di carattere artigianale eseguiti in una tecnica quasi identica e con una corsività di tratti anche maggiore. Mi riferisco ad un mazzo da tarocchi di cui sono arrivati fino a noi solo pochi pezzi, conservati nella collezione Rothschile, presso il Gabinetto dei Disegni del Louvre. Essi vengono considerati cose dell' Italia settentrionale della fine del Quattrocento 53, ma il loro ambito reale e perfino il loro autore sono testimoniati a sufficienza dai rapporti con i dipinti di Giovanni del Ponte.

L'Imperatore si confronta bene col Sant'Antonio abate in una predella del Museés Royaux di Bruxelles o col San Giovanni Battista ex Horne; il Cavaliere di bastoni col San Francesco della anconetta della collezione Earl of Plymouth, Oakly Park (269-270, 267); il Mondo (?) con [201] certi vecchioni che compaiono nella predella con Storie di santa Caterina della tavola del Museé des Beaux-Arts di Budapest (271-272)(soprattutto nella pittoresca increspatura della barba lanosa); il Cavaliere di bastoni col San Giorgio del trittico Kress di Columbia 54 e anche con i due bellimbusti del disegno da cui siamo partiti (266-267). Se si prescinde dall'effetto più "tinto" e quasi in controluce sul fondo oro della carta da tarocchi, che è colorata, si noteranno, oltre alle affinità tipologiche, anche le somiglianze stringenti nei segni di contorno, marcati ma flessibili, e nelle acquarellature sommarie e quasi impressionistiche. Sia il disegno che il Cavaliere di bastoni del tarocco Rothschild trovano una perfetta corrispondenza anche con altri passaggi pittorici di Giovanni del Ponte, come nel giovane re e nel palafreniere che assiste i cavalli sulla destra dell'Adorazione dei Magi (268) delle stessa predella di Bruzelles già citata. Il curioso modo di tenere le mani l'una sull'altra nel giovane in secondo piano del disegno, come se fosse ammanettato, è una singolare formula di Giovanni del Ponte e la si ritrova quasi identica - per esempio - nel cardinale seduto a sinistra del pannello con San Pietro in cattedra della predella di San Piero Scheraggio.

Con Giovanni del Ponte si spiegano molto bene anche le volate grafice dei lunghi ricaschi delle stoffe e quel tanto di sciatto e di spiegazzato che fa dei due giovani del disegno di ubicazione ignota una versione un po' romantica e "bohémienne" degli elegantoni aggiornati alla moda 1425-30 che si vedono in Masolino, in Giovanni Toscani ecc.

_____________________________________

52. Su Giovanni di Marco, più noto come Giovanni del Ponte, arrivo a Firenze dal 1405-10 circa al 1437, si vedano le precisazioni di F. GUIDI, Per una nuova cronologia di Giovanni di Marco, in "Paragone", 223, 1968, pp. 27-46; Idem. Ancora su Giovanni di Marco, in "Paragone", 239, 1970, pp. 11-23.

53. Si veda il catalogo, a cura di PIERRE J.R., della mostra Les Incunables de la collection Edmond de Rothschild, Museé de Louvre, 1974, pp. 27 e 28. I tarocchi Rothschild erano stati pubblicati da L. PUPPI, A proposito di Bonifacio Bembo e della sua bottega, in "Arte Lombarda", 1959, pp. 245-252, che li metteva in rapporto col Bembo, attribuendoli di "Maestro dei tarocchi di Castello Ursino". Il Puppi, p. 250, fig. 13, pubblicava anche un cavaliere di spade del Museo Civico di Bassano, che fa parte della stessa serie dei tarocchi Rothschild.

54. A questo proposito, è interessante riportare l'opinione di R. KLEIN (Les tarots enluminée du XVe siècle, in "L'Oeil", gennio 1967, p. 52) che i "cavalieri" di questa serie siano rappresentati come un san Giorgio.

Re: Giovanni dal Ponte (1385-c.1437) & the Rothschild cards

20Earlier ... [08 Feb 2014] ... I wrote in this thread ...

viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1006

... it resulted, that against earlier expectations of myself the depintore and "garzone of Giovanni dal Ponte" called "Antonio di Dino" should be considered as more probable to have been identical to the playing card producer Antonio di Dino, who is known in the silk dealer article. For this I wrote in the last post of he Antonio di Dino thread:

After some longer research on "Antonio di Dino Canacci" at ...mikeh wrote: I'd like to know how it is determined that this Antonio di Dino is a different person from the cardmaker Antonio di Dino that comes up in Franco's studies, starting in 1441 and making triumph decks in 1452.

Franco Pratesi agreed, that "Antonio di Dino" should be "Antonio di Dino Canacci".

The name form "Antonio di Dino" isn't so rare. In the web might be 4 (or 3) different Antonio di Dino at a comparable time.

One is the engraver, 1428 and 1441, apparently not a rich man.

Another one is part of a sodomy case, around 1437, if I remember correctly.

One is a banker, who works for the Medici (maybe since 1457). This could be identical to Antonio di Dino, the producer of playing cards, but also abacus boards (according Franco's documents, which he commented:

... )."The case of Antonio di Dino is somewhat particular, because the first time that we find him in book 12792 he did not supply cards. He was then mentioned as a maker and supplier of abaci, or counting frames (l. 2r – April 1442). Later on, we find him indicated on one occasion as a "tavolacciaio", maker of tables (12793, 25r – 1449)).

Apparently, his production corresponded to an intermediate level, not as expensive as the cards produced by Antonio di Simone, but not as cheap as those of Niccolò di Calvello, listed below.).

In the web there is Antonio di Dino Canacci, who owns an Abacus school and he's rather active with it (already around 1442, if I remember correctly). The Canacci family is not poor. It seems, that Antonio is a major heir, maybe around the 1450s. It might be, that Antonio di Dino leaves some time after this the playing card industry and becomes the banker.

Palazzo Canacci .... "Nel 1455 Dino di Antonio Canacci acquistò l’immobile di Antonio de’ Bardi ... "

http://wikimapia.org/16905586/it/Palazz ... a-Baldocci

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palazzo_Canacci

In short, there's some doubt, if "Antonio di Dino" had been an engraver or cardmaker at all, but might be just a business man, who (also) dealt with cards and also dealt with abacus boards and "tables" and also organized the abacus school.

viewtopic.php?f=11&t=1006

... it resulted, that against earlier expectations of myself the depintore and "garzone of Giovanni dal Ponte" called "Antonio di Dino" should be considered as more probable to have been identical to the playing card producer Antonio di Dino, who is known in the silk dealer article. For this I wrote in the last post of he Antonio di Dino thread:

There's a new information about the person "Antonio di Dino" ... this person ...

http://cds.library.brown.edu/projects/c ... D+50008445

... not identical to Antonio di Dino Canacci, who was mostly researched in this thread.

Franco Pratesi got an information of Elisabetta Ulivi, likely author of ...

"La matematica dell'abaco in Italia: scuole, maestri, trattati fra XIII e XVI secolo."

The short note presents the known fact, that this Antonio di Dino is not identical to Antonio di Dino Canacci, but additional to the already earlier known details we find from her the expression "tavolaccino" in context to this second Antonio di Dino.

Franco had independently in his earlier research (silk dealer articles) noted in context of the Antonio di Dino, who made playing cards:

"He was then mentioned as a maker and supplier of abaci, or counting frames (l. 2r – April 1442). Later on, we find him indicated on one occasion as a "tavolacciaio", maker of tables (12793, 25r – 1449)."

The note about "abaci" had led to the person of Antonio di Dino Canacci, but the additional "tavolacciaio" leads to the second Antonio di Dino, who additional has the quality, that he in 1441 was called a "dipintore".

The odds seem now much better for the assumption, that the second Antonio di Dino is the right man for the well documented playing card production (silk dealer articles)...

http://trionfi.com/naibi-aquired#3-1

... , and NOT Antonio di Dino Canacci.

******************

... :--) ... For the research of Giovanni dal Ponte this condition (if the assumption is true) would mean, that he had a "garzone" Antonio di Dino (* 1402), who owed him some money (around 1427-30), and who later started a business as a playing card producer (first noted in 1439) and then also as Trionfi card producer (first involved in a Trionfi card deal 1445 and later since 1452 clearly the producer).

Work of Giovanni dal Ponte

Card of the Rothschild cards, possibly Trionfi cards

A similarity between a Tarocchi card with unknown author and an object created by a known artist might mean, that the artist had been producer of both works.

But it naturally could also mean, that the playing card producer imitated this other artist. "Garzone" and other pupils often imitate their masters. In this case Garzone Antonio di Dino had been later (likely) confirmed playing card producer, and a deck has in fragments (Rothschild cards) survived, possibly produced by Antonio di Dino.

Antonio di Dino produced "expensive decks" in 1441, twice mentioned in the lists of the silk dealers. Both deals speak of "24 soldi", so much higher than later cheap Trionfi deck prices.

Alternatively:

If Giovanni dal Ponte himself was already active in the playing card business, then Antonio di Dino would look like a natural follower.

Huck

http://trionfi.com

http://trionfi.com